The case for prisons

The purpose of prisons, and evidence for their efficacy

“It is safe to assume that if there were no prisons there would be a lot more crime.” (Halliday Report, 2001)

Introduction

Prisons are an essential institution for providing public safety. But more and more seem to forget why—what is the purpose of prisons?

Prisons exist for the benefit of society at large, not for those imprisoned. Contrary to common modern perception, the primary purpose of prisons is not rehabilitation.

Prisons reduce crime through two primary mechanisms. First is incapacitation, to separate criminals away from civil society and prevent them from committing additional crimes in a given period. A secondary mechanism is deterrence, to prevent people from committing crimes in the first place.

Prisons serve other societal functions, such as retribution and justice for the public peace. Rehabilitation, however, should be low on the list of priorities.

The power law of crime

Perhaps the single most important fact of criminology is that a large share of crime is committed by a small group of persistent repeat offenders, as I have previously documented extensively.

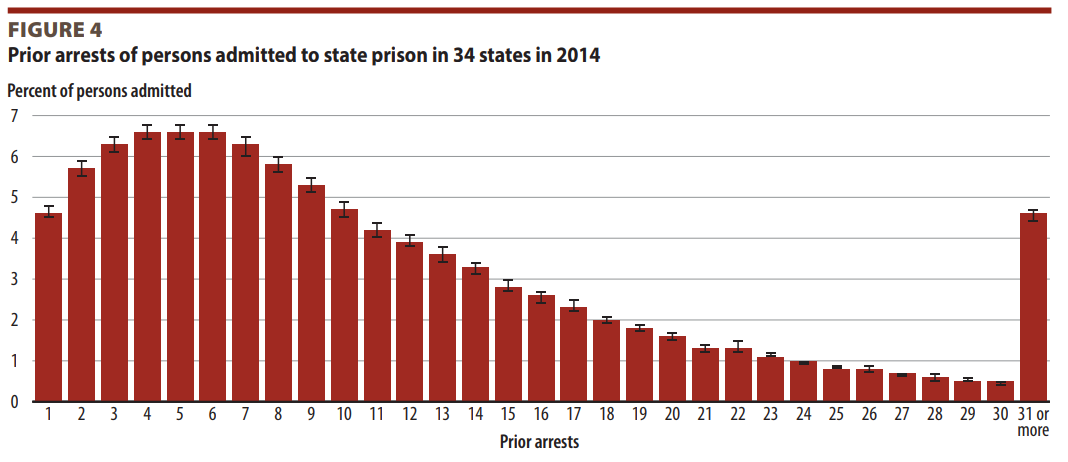

One illustrative example: people who are imprisoned in the United States have typically been arrested many times. An analysis showed that less than 5% of people admitted to prison had only been arrested the one time that led to the prison sentence (Durose & Antenangeli, 2023). It was more common to have been arrested 30+ times than having only the single arrest that led to imprisonment. The median number of arrests was 9, and more than 3 out of 4 prisoners had been arrested 5+ times.

Another example is that nearly a third of shoplifting arrests in 2022 involved just 327 people, who collectively were arrested and rearrested more than 6,000 times.

But the reality is even worse than this, for criminals (when asked) admit that have often committed dozens of crimes for every crime they were arrested for (Minkler et al., 2022).

A corollary of the criminal power law is that a large fraction of crime can be prevented by addressing a surprisingly small number of persistent offenders.

The effectiveness of policing and prisons

Incapacitation

In 2020, three prolific burglars were on the loose in Leinster, Ireland. Together they had accumulated over 200 convictions. But one day, they all died in a traffic accident. As a result, the robbery rate plummeted.

In a well-governed society, citizens would not need to wait for such accidents to occur. The same effect could have been achieved much earlier through incapacitation. Had they been incapacitated after their 10th conviction each, 170 convictions and possibly untold number of unconvicted crimes could have been prevented. With proper enforcement, the robbery rate in Leinster could have plummeted before their deaths.

Incapacitation prevents crime—that is, the crimes they would otherwise have committed in the incarceration period had they been free. Recall that persistent offenders will often commit many offenses in a single year. Beyond that, an additional minor benefit is people age while in prisons, reducing recidivism rates.1

These points not only make intuitive sense, they are also empirically well-established. El Salvador have illustrated the effectiveness of incarceration at the national scale. In 2015, they held the title of the highest homicide rate in the world, with a peak homicide rate of over 100 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. But after a focused effort to imprison gang criminals, the homicide rate has plummeted. In 2023, the homicide rate in El Salvador was just 4.5 per 100,000—substantially lower than in the United States (6.7 per 100,000).

A natural experiment in Italy provided further evidence of the efficacy of incapacitation (Barbarino & Mastrobuoni, 2014). Eight collective pardons between 1962 and 1990 led to a large fraction of prisoners being released. The releases led to a large increase in crime, confirming that many crimes were otherwise being prevented while these criminals were incarcerated.

The exact number of crimes prevented by incapacitation is difficult to estimate. It requires inferring a counterfactual, namely the number of crimes the person would have committed if he or she were free. One estimate by Sweeten & Apel (2007) suggested that 1 year of incapacitation prevented 6.2 to 14.1 offenses for juvenile offenders, and 4.9 to 8.4 for adult offenders. Another estimate comes from Levitt (1996), who exploited exogenous variation in state incarceration rates induced by court orders to reduce prison populations. His estimate suggests that the incarceration of one prisoner reduces the number of crimes by approximately 15 each year.

Deterrence

Beyond the direct benefit of incapacitation, policing and incarceration also act as deterrents. In their review of criminal deterrence, Chalfin & McCrary (2017) discuss the large body of evidence supporting this notion.

One example is the 1995 randomized controlled experiment conducted by Sherman and Weisburd in Minneapolis. They tested whether (experimentally) increasing the police presence in certain hot spots reduced crime in those areas. It did.

Deterrence has since been confirmed by other experimental and quasi-experimental work (Chalfin & McCrary, 2017).

Researchers generally agree that deterrence is mainly a function of the likelihood of being caught, but less so the severity of punishment if caught. So increasing police presence to increase likelihood of catching criminals has a deterrent effect, but, say, the deterrent effect of increasing sentence length is less noticeable.

For this reason, some conclude that longer sentences do not help. But that would be to forget the effect of incapacitation.

Rehabilitation

It is one thing to favor better conditions for prisoners, which can be justified on various grounds. But the notion that it’s the key to low recidivism rates rests on shaky ground.

When discussing the purported efficacy of the rehabilitation model, the discussion will inevitably turn to the Nordic societies.

But after much research on the topic, I have increasingly come of the opinion that no one really knows how to rehabilitate criminals effectively, and certainly not to the extent that it deserves priority over incapacitation and deterrence. As I have discussed at length in two previous posts, partially summarized elsewhere, there are good reasons to doubt that low Nordic recidivism can be attributed this rehabilitation model.

For one, the recidivism rate in the United States does not appear to be much higher than in Denmark, Finland or Sweden. Only Norway seems to have meaningfully lower recidivism rate. But Denmark, Finland and Sweden are all much more similar to Norway in their rehabilitative approach than to the United States.

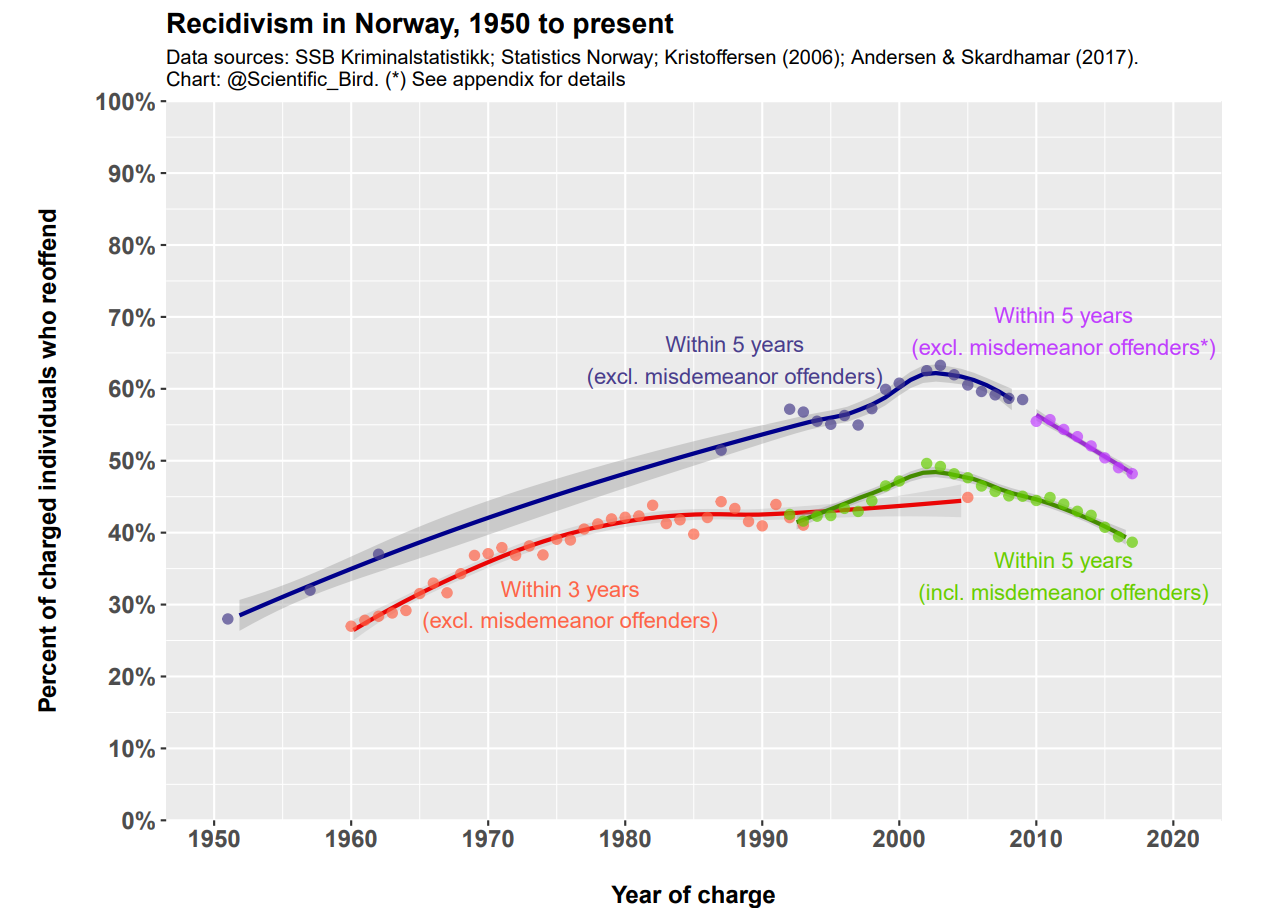

Furthermore, Norway had the lowest recidivism rate in the 50s and 60s, prior to the introduction of their 90s rehabilitation reforms.

These and other findings suggest that the recidivism rate is mostly governed by many other variables that differ between time and place, and there is little reason to give credit to the prison rehabilitation model.

Final thoughts

If our goal is to reduce crime, what policy implications follow from these realities?

The criminal power law tells us that much crime can be prevented by addressing the most persistent repeat offenders. A simple suggestion would be to greatly increase likelihood and length of incarceration as a function of previous offenses. Even minor offenses can be destructive in sufficiently large numbers, so each offense should not be judged independently from other offenses the person has committed.

Longer sentences for repeat offending are effective, if for no other reason than incapacitation. A person should not be able to accumulate 10 arrests without a lengthy prison sentence. Even worse, those 10 arrests were in all likelihood accompanied by countless other offenses for which no arrests were made.

Additionally, persistent career criminals are overwhelmingly known by the police, and their guilt is not in question. Harsh penalties upon repeat offenders therefore carries little risk of false positives.

However, it all starts with proper policing and actual enforcement of the law. Some Western countries have recently experienced a reduction in enforcement: a lot of low-level crimes no longer lead to any charges. An effective “tough-on-crime” approach should first and foremost aim to greatly increase the clearance rate of such crimes, and devote attention to charging offenders. If many crimes are “effectively legal”, why would a criminal be deterred from offending?

If you enjoyed this piece, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Not only is support greatly appreciated, it also meaningfully increases the amount of time I can afford to spend on producing content. Typically every other article I write will be restricted to paid subscribers. As a paid subscriber, you will gain access to those, including all previous restricted articles.

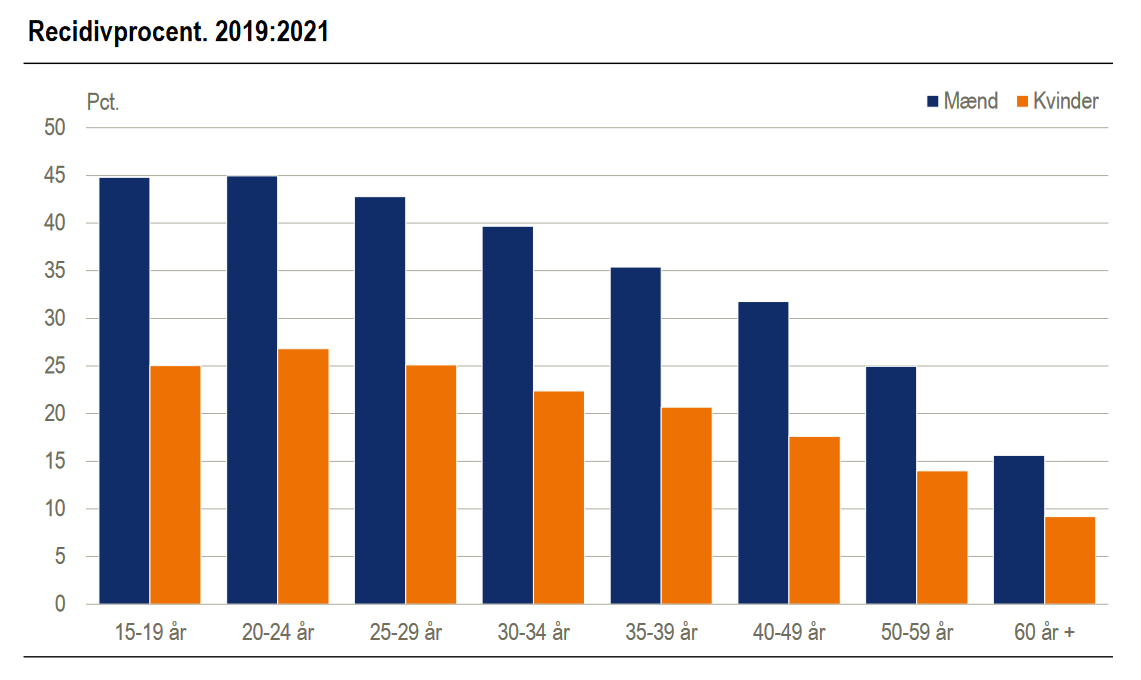

Consider for example the recidivism rate by age in Denmark, for men (“mænd”) and women (“kvinder”), respectively. Source: Statistics Denmark (2023).

.

re: "But Denmark, Finland and Norway are all much more similar to Norway in their rehabilitative approach than to the United States" -- typo, you meant but Denmark, Finland and Sweden, no?

I'm in Sweden. To the extent we know how to rehabilitate criminals, what we know how to do is how to rehabilitate ethnic Swedes. (And not all of them). If you would like to re-join the ranks of the law-abiding, we actually know how to instill better habits in you, and make space for you in our society, once you have repented and we can see that the repentance is sincere. This doesn't work for rehabilitating gang members, actual neo-nazis, or jihadists. You cannot rehabilitate people who at are war with society itself, or are sociopaths. This ought to be obvious to everybody, but for some reason isn't.

As surprising as it sounds to some people, prisons work. We really don’t know how to rehabilitate our most dangerous criminals, nor how to keep impulsive youths from starting down that path. So prison and effective policing are the most effective solution for the foreseeable future.