When few do great harm

Power laws in criminal behavior

I summarize some data illustrating how a small number of criminals are responsible for a large fraction of crime.

While the terms “power law” or “Pareto distribution” have precise mathematical definitions, colloquially they have come to be used to convey an important fact: in many contexts, few account for much. For example, a small fraction of people hold a large fraction of overall wealth. Here I will consider it in the context of crime, where a small minority of repeat offenders are responsible for a large fraction of all crimes.

Criminal and delinquent behavior approximately follow such power laws. It is observed for arrests, convictions and even self-reported delinquent behavior. For example, Cook et al. (2004) compared convictions in a UK study and self-reported delinquency from a US dataset and found that both were well-described by a power law. Other UK data show that 70% of custodial sentences are imposed on those with at least seven previous convictions or cautions, and 50% are imposed on those with at least 15 previous convictions or cautions (Cuthbertson, 2017).

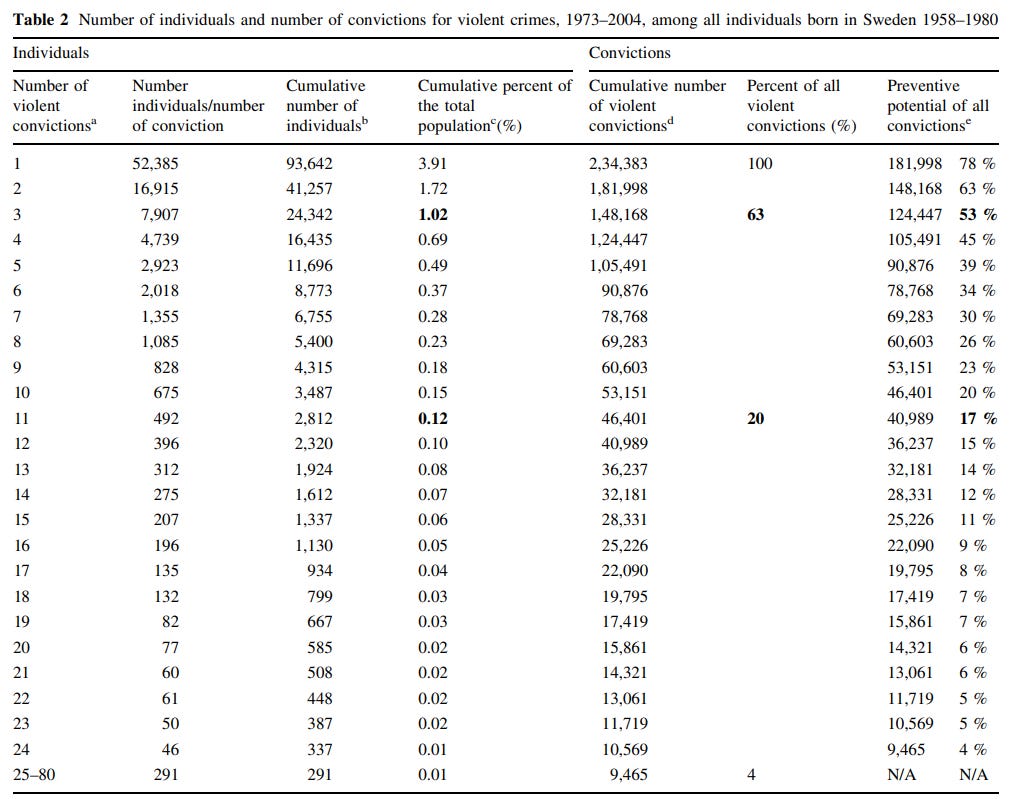

But perhaps the most illustrative study is by Falk et al. (2014), who used Swedish nationwide data of all 2.4 million individuals born in 1958–1980 and looked at the distribution of violent crime convictions. In short, they found that 1% of people were accountable for 63% of all violent crime convictions, and 0.12% of people accounted for 20% of violent crime convictions.

Below the mean number of convictions by percentile among offenders is illustrated, a very Pareto-like distribution. At the extremes there are people who are not merely arrested but convicted of 10, 20 or even more than 50 violent crimes. High-persistence criminals were almost all male, they typically started their first crime young, and very often had major mental disorders and substance use disorders.

Another notable fact: approximately half of violent crime convictions were committed by people who already had 3 or more violent crime convictions. In other words, if after being convicted of 3 violent crimes people were prevented from further offending, half of violent crime convictions would have been avoided. Other similar quantities are summarized in the table below.

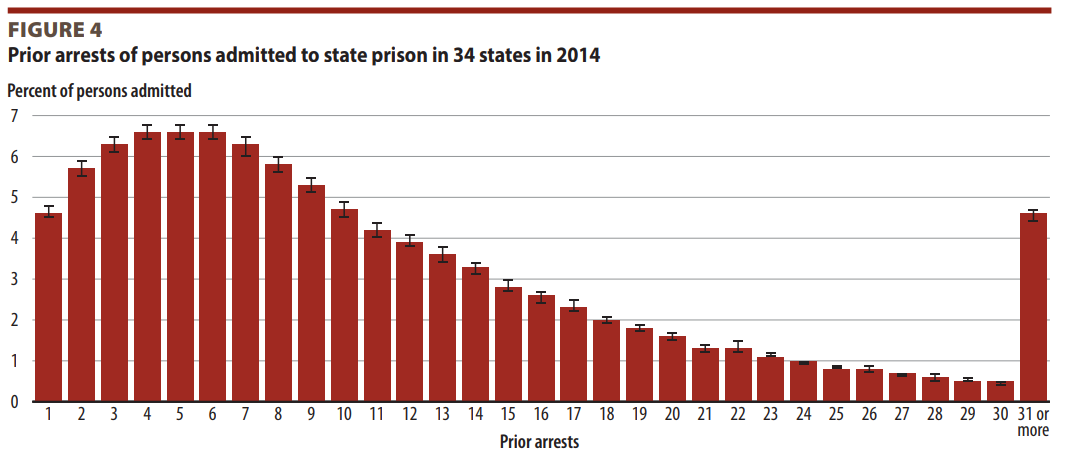

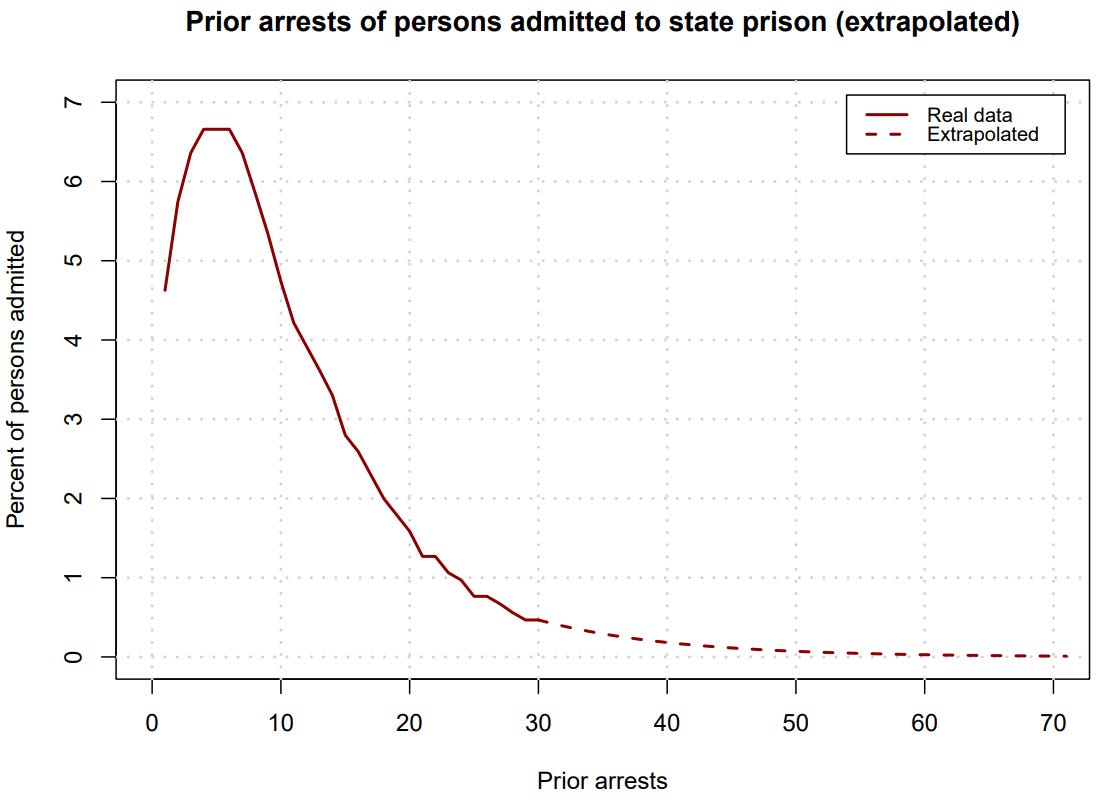

America has a reputation of a very harsh penal system that is very quick to lock anyone up. It may then be the case that Americans are incarcerated long before they can rack up many crimes. But is this perception justified?1 Pryor et al. (2018) find that 72.8% of federal offenders sentenced had been convicted of a prior offense. The average number of previous convictions was 6.1 among offenders with criminal history. More recently, Durose & Antenangeli (2023) used prison records to analyze arrest history of people admitted to state prison in the United States. The distribution of prior arrest counts is shown below.

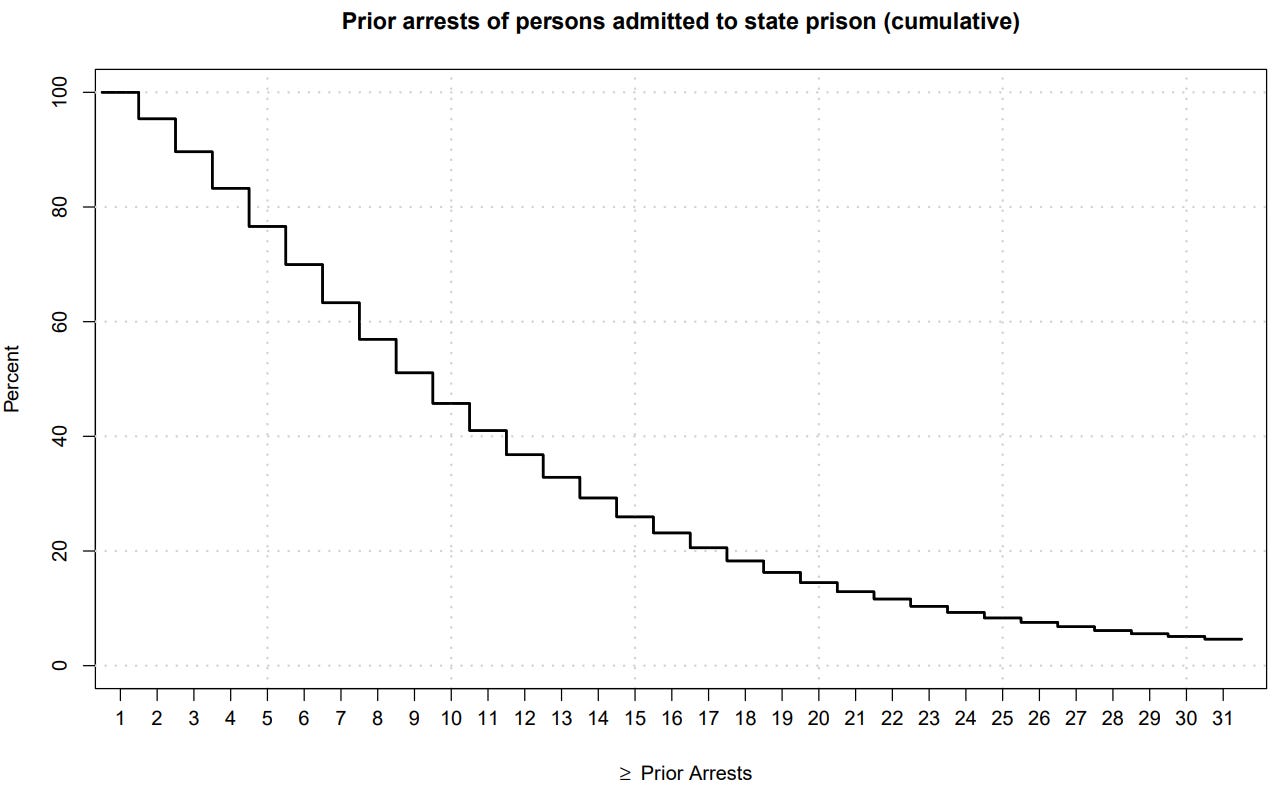

Generally we are more concerned with how many people have a certain number of prior arrests or more. I converted the given numbers to such cumulative figures, which are illustrated below.

It is clear that people tend to have many arrests before being incarcerated. The data show, among persons admitted to state prison, more than 3 out of 4 have at least 5 prior arrests, including the arrest that resulted in their prison sentence. Going further into the tail: 46% (almost 1 in 2) had 10 or more prior arrests, 14% (1 in 7) had 20 or more prior arrests, and 5% (1 in 20) had 30 or more prior arrests. Indeed, having 30 or more prior arrests when admitted to state prison was more common than having no arrest other than the arrest that led to the prison sentence (i.e., 1 prior arrest). Further, it was more common to have 9 or more prior arrests than it was to have 8 or fewer.

In the original graph, “31 or more” is high because it is the aggregation of all arrest counts 31, 32, 33, and so on, until the largest existing number of prior arrests. To consider arrest numbers higher than 31, I used a simple extrapolation method2. From this extrapolation I speculate that 1% of people admitted to state prison had approximately 46 or more prior arrests, and 1 in 1000 may have had as many as 64 or more prior arrests. The precise numbers, however, are not given in the report and these extrapolations should be taken with a grain of salt.

Another extreme illustration of the arrest distribution is the following. The NYPD reported that they made over 13,600 arrests on the in the subway system in 2023. Of those arrests, 124 people were arrested 5 times or more each in the subway system in 2023 alone. Combined, these 124 people had been arrested over 7,500 times in their lifetimes, an average of more than 60 arrests per person.

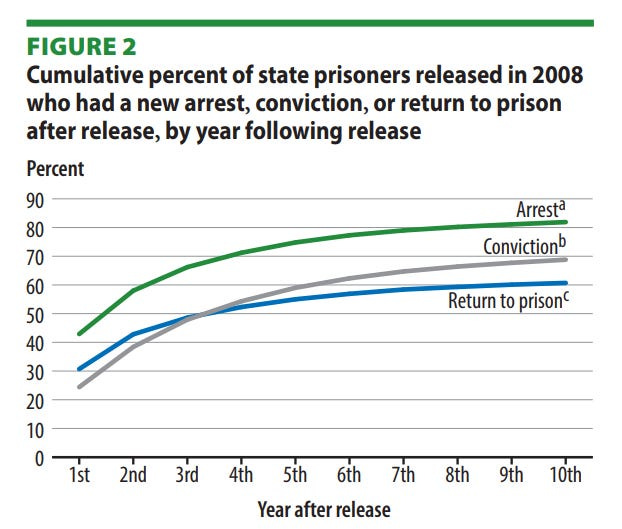

We can also consider redicivism statistics. Antenangeli & Durose (2021) found that after prisoners were released, within 10 years, 81.9% had been arrested at least once, 68.8% convicted, and 60.7% reincarcerated. This is illustrated below.

A different analysis by the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform finds that for the crime of homicide: “Overall, most victims and suspects with prior criminal offenses had been arrested about 11 times for about 13 different offenses by the time of the homicide. This count only refers to adult arrests and juvenile arrests were not included.” Again, we see that homicide offenders typically have been arrested numerous times before they commit their first homicide. They also note that some 500 identifiable people account for 60-70% of all gun violence in the District of Columbia.

The fact that a small minority is responsible for a large chunk of crime is true for shoplifting and burglaries as well, perhaps to an even greater extent. Data from New York City finds that a tiny number of shoplifters commit thousands of theft. The police stated that nearly a third of all shoplifting arrests in the city in 2022 involved just 327 people, who collectively were arrested and rearrested more than 6,000 times. Thus 0.00386% of New York City’s population (327 out of 8.468 million, 1 in ~26,000) accounted for nearly a third of all shoplifting arrests in the city.

As illustrated by a different study, crime in New York City is not only disproportionately committed by few people, it also disproportionately affects specific local areas. They find that 14% of streets in the city produce 75% of property crime and 10% of streets produce 75% of violent crime.

A particular incident vividly illustrates of how few people can be responsible for a large fraction of crime. In Leinster, Ireland, the number of burglaries plummeted after three criminals died in a car crash. These three criminals together had more than 200 previous convictions. Similarly, in London local bike thefts fell by 90% as 11 individuals (not 11 percent) from a bike theft gang were caught in a single police shift.

An implication of the fact that most crimes are committed by repeat offenders is that there are more victims than offenders3. More people get robbed than there are robbers, more victims of rape than there are rapists4, and so on. More generally, few people can cause great harm to society at large. Of course, the victims themselves experience this damage most directly. But the harms of crime extend beyond those directly affected. It is difficult to precisely estimate the financial costs of crime, however estimates are high (e.g., Wickramasekera et al., 2015; Anderson, 2021; Miller et al., 2021). Beyond direct tangible costs are also opportunity costs, including the value of institutions and services that people don’t have access to because of the prevalence of crime. The benefits of reducing crime, particular in the United States, are therefore great. And the data shows that these benefits can be enjoyed by addressing a surprisingly small number of repeat offenders.

Lewis & Usmani (2022) show that, while the US has much higher incarceration rates than other highly developed nations, the incarceration rate is not necessarily very high relative to the rate of serious crime. On the other hand, they show that the nation is very under-policed, meaning a low number of police officers per-capita and particularly few on a per-crime basis.

I assumed that in the tail the frequency fell exponentially with increasing number of prior arrests by some rate r. Then I fitted r such that the entire distribution summed to 100% (the extrapolated tail filling the otherwise missing 4.6%). The real data along with the extrapolated estimates can be seen below.

In theory, you could have a situation where there are more offenders than victims, because certain incidents of crime can have multiple offenders. However, in practice the actual contribution of this to offender/victim counts pales in comparison to the number of crimes that are committed by repeat offenders (in a nontrivial amount of cases, offenders who commit dozens of crimes). For example, according to NCVS data, violent crime incidents have on average 1.2–1.3 offenders, just marginally above 1 (Table 6; Beck, 2021). On the other hand, the data I have summarized herein show the typical criminal will rack up many crimes (i.e., 5+), and a nonnegligible fraction of criminals will commit up to dozens of crimes. So it certainly remains true that there are more victims than offenders.

Occasionally regarding the issue of rape, activists rhetorically ask something like “Why does every woman know another woman that was raped but no man knows a rapist?” The most obvious explanatory factor is that people are unlikely to publicly acknowledge their own crimes; crimes often committed behind closed doors. But it is also because there legitimately are more victims than offenders, because of the extreme repeat offender phenomenon discussed in this post.

Excellent post!

I'll add that the opportunity costs you mentioned are potentially major (much more so compared to other contexts where the term is often used), because they stretch across many domains (educational. work-related, leisure activities, etc), and lead to a reduction of welfare and opportunities to a point below a threshold which allows people to live a normal life.

You won't hear much of this in common disucussions of criminal justice policy, and debates about who are the people who benefit or are harmed by policing.

Great article. Now who wants to connect the dots and describe the this small percentage of the population that is doing most of the damage to society?

In the US, about 14% of the population commits about 50% of the murders. If we narrow it down by sex and age, it's about 3-4%. That's just the direct cost in lives. There are billions in indirect cost due to property theft and social programs that do not work. As well as paid positions like diversity officers that basically do not contribute to the economy.

Is the US spending 10-20% of their GDP just dealing with this group? I don't think there has been studying trying to quantify the damage that this group does to society.