The myth of the Nordic rehabilitative paradise

Interpreting recidivism rates and understanding their causes

Introduction

It’s a well-documented fact that a small number of repeat-offending criminals are responsible for a large share of all crime. The primary reason why prisons effectively reduce crime is exactly because they prevent the crimes that these offenders would otherwise (had they not been incapacitated) commit over the duration of their imprisonment. The beneficial effect of incapacitation is empirically well-supported. For example, Barbarino & Mastrobuoni (2014) showed that collective pardons, which led to a large number of prisoners released in Italy, resulted in a large crime spike.

When prisoners are released, many of them reoffend. But reported recidivism rates differ markedly between countries. A widely held belief is that the Nordic countries are great bastions of rehabilitation: by focusing on rehabilitation rather than punishment, they have managed to achieve remarkably low recidivism rates. Or so the story goes.

This notion, however, is largely a myth. At the very least, this Nordic rehabilitative success story is greatly exaggerated. The aim of this piece is to set the facts about recidivism straight. It will be shown that the American recidivism rate is much closer to that of the Nordic countries than often believed. Further, I will explain why cross-national comparisons of recidivism rates are often highly misleading due to differences in how recidivism is operationalized and measured, and that this accounts for much of the typically reported disparities. The recidivism figure cited for Norway—the country most often hailed as the great triumph in this regard—will be used as a case study to illustrate the problems that can arise.

It will become clear that it’s a mistake to attribute differences in recidivism rates to the effect of rehabilitation, as recidivism is strongly influenced by other external factors. What's more, there is little compelling evidence to suggest that prisons differ greatly in how effectively they rehabilitate, or that therapy is effective at reducing recidivism.

Recidivism in the United States

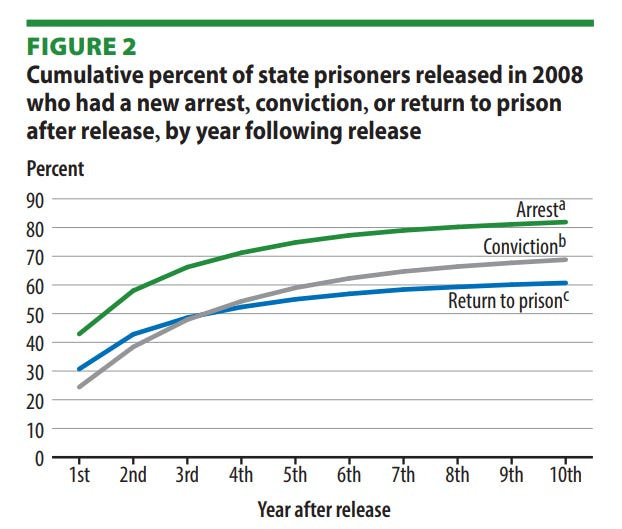

Before we can compare with other countries, we should establish the situation in America. The following figure gives the most recent summary of the American recidivism rates (Antenangeli & Durose, 2021). The figure reveals two things of utmost importance when we compare recidivism rates. First, recidivism rates depend enormously on the duration of the follow-up period under discussion. Less than 50% are rearrested within the first year, but more than 80% are within 10 years.

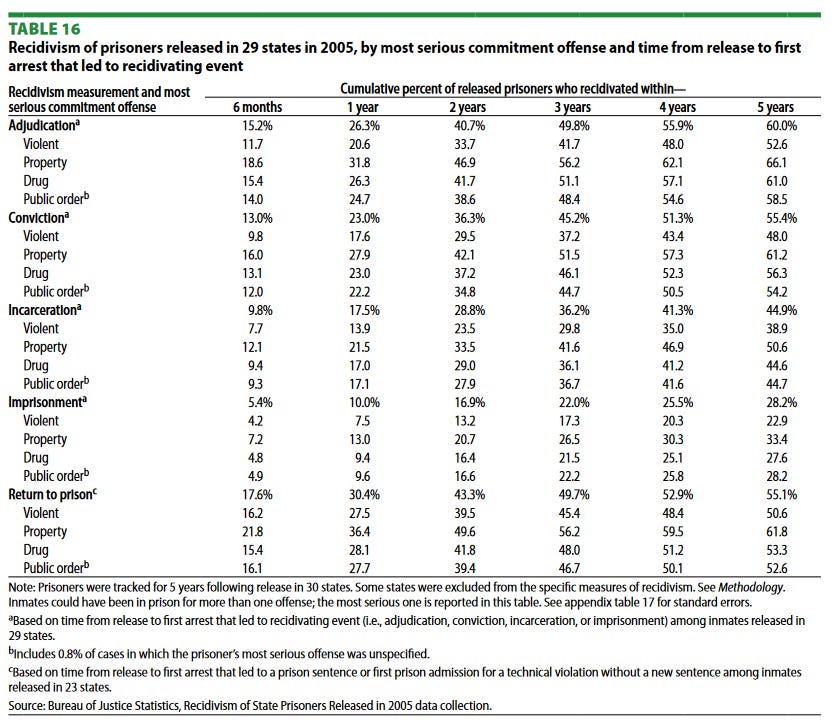

Second, the rates also depend a lot on how “recidivism” is operationalized. How sensitive the “recidivism rate” is to definition is made even clearer in an earlier BJS report, and is illustrated below (Durose et al., 2014). According to different measures, the American 2-year recidivism figures were 40.7% (adjudication), 36.3% (conviction), 28.8% (incarceration), 16.9% (imprisonment), and 43.3% (return to prison), respectively.1

International recidivism

Why comparing countries is difficult — the Norwegian case

As reported by US NEWS, “The Norwegian prison system boasts a 20 percent recidivism rate – compared to the 76.6 percent recidivism rate in the U.S.” According to their reporting, this purported Norwegian rehabilitation success story inspired prison reforms in North Dakota to adopt Norwegian practices.

These kinds of comparisons are commonplace (BBC News, 2019; Browne, 2020), yet they are hugely misleading for the purpose of evaluating rehabilitation effectiveness. Recidivism rates are measured very differently depending on jurisdiction and context. This 20% vs 76.6% comparison is particularly egregious as the Norwegian figure is more narrowly defined and measured over a much shorter time frame. The American 76.6% figure above was based on rearrest within 5 years (Durose et al., 2014), whereas the Norwegian 20% figure described the number who received a new prison sentence or community sanction that became legally binding within 2 years (Kristoffersen, 2013). Both figures refer to prisoners released in the year 2005.

Of the American recidivism statistics mentioned in the previous section, the 28.8% incarceration figure is arguably the most comparable in definition to that of the 20% Norwegian figure.2 Thus, when the comparison is closer to apples-to-apples, the difference between Norway and the United States is far more modest.

Another challenge when comparing nations is that court proceedings can be lengthy before a conviction is finalized. In some jurisdictions (e.g., Norway), they operationalize recidivism as both an offense and conviction that has to occur within the follow-up period, whereas in other cases only the offense needs to occur within the period (Yukhnenko et al., 2020).

Beyond the issue of comparing equivalent definitions of recidivism, there are numerous relevant societal factors beyond prison rehabilitation efforts. The distribution of crime types will affect the composition of sentenced offenders and therefore the reoffending rate. In general, observed recidivism rates are lower for sexual and traffic crimes, high for property crimes, and in the middle for violent and drug crimes (Yukhnenko et al., 2023). Furthermore, differential willingness to use suspended sentences and/or probation indirectly affects the offending type composition among those who are imprisoned.

Kristoffersen (2013) has shown how relevant this can be in the Nordic context. In all of Europe, Norway has been unique in the extent to which they have given prison sentences for crimes like speeding in traffic.3 Traffic crimes have low reoffending rates in all the Nordic countries, so the imprisonment of these individuals at low risk of reoffending artificially brings down the reoffending rate among released prisoners. In contrast, (perhaps due to greater use of non-prison punishments) Norway had the smallest proportion of released offenders sentenced for thefts; and those sentenced for theft have the highest reoffending rates across the Nordic countries. If all traffic offenders had instead been on probation rather than in prison, that alone would bring the Norwegian recidivism figure from 20% to 25%. That is even closer to the 28.8% American reincarceration figure cited above. In short, who is imprisoned (and who instead receives fines, probation, or suspended sentences) can meaningfully change the recidivism rate of released prisoners through compositional effects alone. Much of the measured Nordic differences can be attributed to such compositional effects.

The base rate of crime and the size of the population who receive prison sentences in the country may also affect recidivism rates. Yukhnenko et al. (2023) provided evidence of this and they explain: “the more criminogenic a society is, the higher the recidivism rates (given other factors are held constant).” Thus, rather than reflecting rehabilitative differences, recidivism figures can also partly be ascribed to differences in the overall level of criminality. This is an important consideration because the United States has a far higher rate of serious violent crime than the Nordic countries.

There is yet another surprising but potentially relevant difference. Foreign prisoners make up a disproportionate fraction of Norwegian prisoners and, according to Mulgrew, about half of them are expected to be deported at the end of their sentence. But how many foreign convicts are deported in practice? According to Aftenposten, 794 foreign convicts were deported and were formally barred from re-entry in 2011. The following year 1,019 foreign convicts were deported. For context, the nationwide prison population in Norway is only about 3,000-4,000 (give or take) at any given time, so this number of deportees is not inconsequential. Deported individuals obviously cannot contribute to recidivism statistics any further, except if they manage to return despite being barred from re-entry, which can happen (and when they do, they are often discovered due to recidivism). Excluding deportees could plausibly move the recidivism rate a few additional percentage points.4

In summary, comparing recidivism rates between countries is very difficult and can easily be misinterpreted. The differences between the United States and Norway is much smaller when comparisons are closer to apples-to-apples, though a difference favoring Norway still exists. But even this remaining difference cannot be assumed to be due to rehabilitation differences, because the societies differ in many other ways. As noted, when relevant confounders are controlled for, the difference becomes even smaller. And this is unlikely to be an exhaustive set of relevant confounding variables.

Comparing the Nordic countries with the United States

Despite all the caveats mentioned about comparing international recidivism rates, it would unsatisfactory if we didn’t compare the Nordic and American recidivism rates as best as we can.

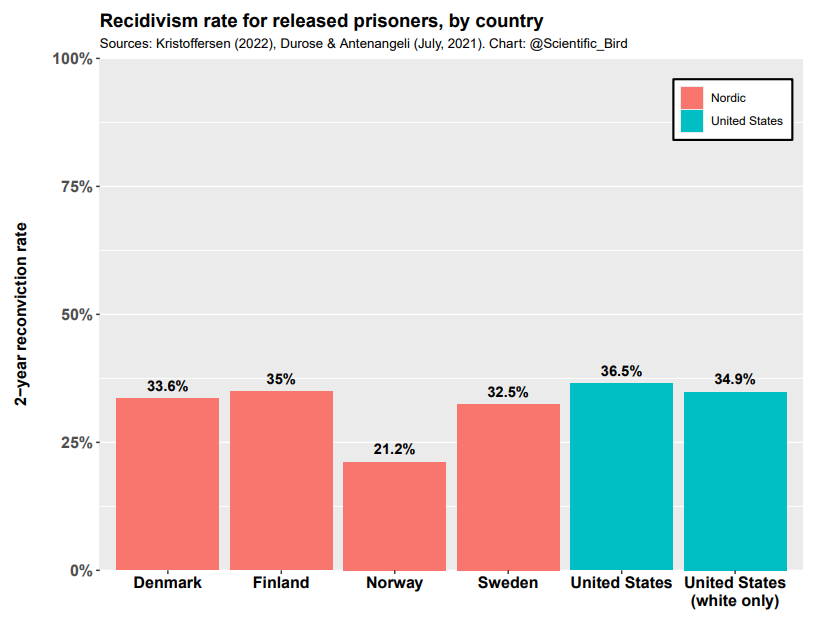

For available data that gets us the closest to an apples-to-apples comparison, I lean on recent Nordic data provided by Kristoffersen (2022) and American data from Durose & Antenangeli (July, 2021). The recidivism measure used is the 2-year reconviction rate for released prisoners.5 The comparative results are displayed in the figure below. Because I can anticipate that some would ask the question, I have also included the American recidivism rate for white individuals only.

The first thing to notice is that Nordic recidivism rates are by no means exceptionally low, contrary to idealistic notions many have about the region. In Denmark, Finland and Sweden, about 1 in 3 is reconvicted within 2 years. Even in Norway, about 1 in 5 are reconvicted, and a much larger share rearrested within a longer time frame (Andersen & Skardhamar, 2014). As already discussed, much of Norway’s observed advantage over the other Nordic countries is likely attributable to non-rehabilitation factors.6

Though the United States recidivism rate is higher than that of the Nordic countries, most of the differences are exceptionally small. It does not stand out as an outlier. This is even more remarkable when one considers that the United States is a huge outlier (among developed countries) in terms of rate of serious violent crime and overall imprisonment rate. If anything, we ought to seriously consider the possibility that the low reconviction rate in America is indicative of under-policing. Yet another common misconception is that America is over-policed. On the contrary, the reality is that the number of police is very low relative to its level of serious crime (Lewis & Usmani, 2022).

The effectiveness of rehabilitation practices

The claim that the Nordic countries are far more effective at rehabilitation is typically based on their recidivism rates supposedly being remarkably low. We now know that this isn’t even the case. But even the small remaining differences cannot simply be attributed to differences in rehabilitation. This is because recidivism rates are affected by many factors outside the control of the prison itself. In fact, differences in recidivism rates across prisons probably have much more to do with the composition of prisoners and the wider socio-cultural and demographic context than to the prisons themselves.

A study by Yu et al. (2022) is particularly illustrative in this regard. They looked at how recidivism rates differed between prisons across Sweden. The prisons differed greatly in their recidivism rates, so a naïve comparison would have you believe that they rehabilitated to very different extents. But, to test whether the prisons themselves were responsible for the recidivism rate differences, they followed 37,891 individuals released from prisons and compared the same prisoners when they were released from a different prison. In these within-person comparisons, the large prison gaps in recidivism rates became very small and non-significant. No prison was substantially more criminogenic or “rehabilitative” than the other. This is further confirmation that large recidivism differences can be a mere manifestation of prisoner composition, and not caused by the prisons themselves. It gives us even greater reason to suspect that external factors might play the dominant role in the measured differences between countries.

Therapy

The rehabilitation vision (including prison abolitionists) is very often accompanied by advocacy of therapy and social work as intervention. It is suggested that therapy would solve the “root causes” of crime, and thus dramatically reduce recidivism rates. Prison abolitionists sometimes argue that therapy could entirely replace prisons. Are these beliefs well founded?

Beaudry et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 29 randomized controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of psychological interventions. They found that there was substantial publication bias in favor of the interventions. After accounting for this, by excluding the smallest studies (<50 participants in intervention group), they found that therapy did not significantly reduce recidivism.

Similarly, Olsson et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review of psychosocial interventions targeting juvenile criminals. They found no noninstitutional psychosocial intervention that significantly reduced recidivism among juveniles.

The evidence is thus strongly opposed to the idea that therapy can greatly alleviate overall recidivism rates. Future research with much more statistical power may possibly find that therapy has a small beneficial effect. It is also possible therapy can be effective for addressing some risk factors of crime (e.g., substance abuse), but that would still be consistent with the effect being small in the aggregate. Because there is publication bias in favor of therapy’s effectiveness, future research should preferably also be preregistered. Indeed, publication bias is a serious concern more generally. Any research aiming to show that an intervention is effective needs to meet a high bar of evidence before it can be considered fully convincing.

What does matter for recidivism?

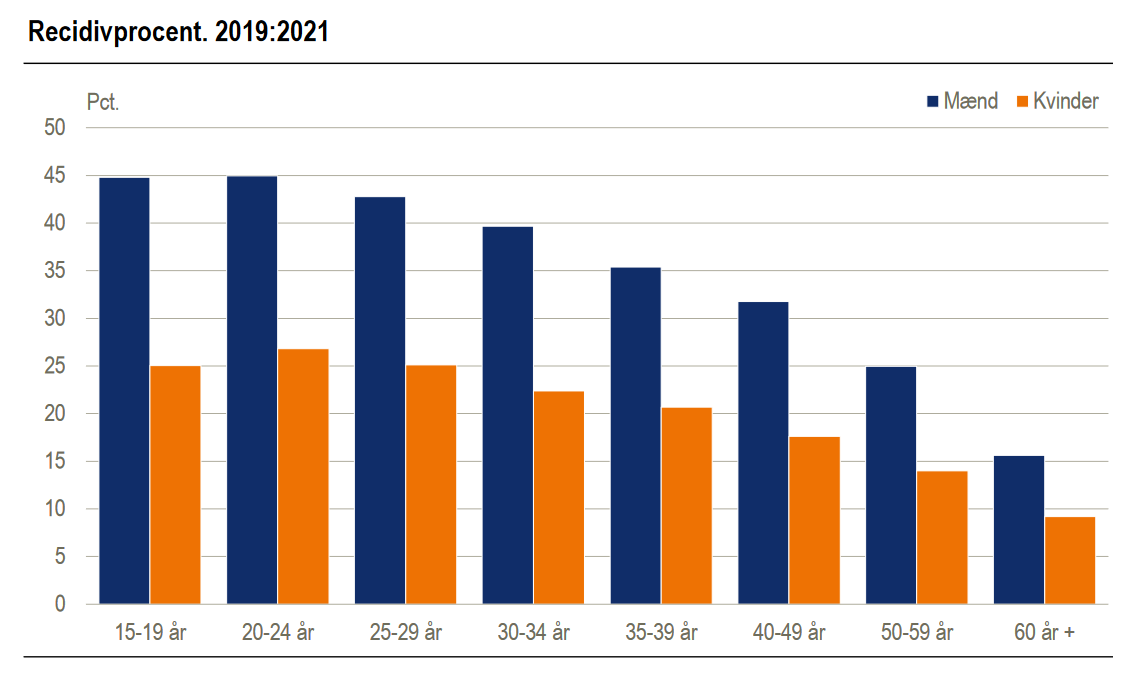

There are some correlates of recidivism which are fairly obvious, such as age and sex. This is illustrated for Danish data below.

But we want to find the causal risk factors that are most amenable to intervention. Age of released prisoners can technically be influenced by sentencing length. Longer prison sentences—apart from the much more relevant effect of a greater incapacitation period—have the small additional benefit of an aging effect. Thus, this is technically a way to reduce recidivism, but it is surely an answer many would find unsatisfactory.

The evidence discussed so far is disappointing for achieving the dream of complete rehabilitation, or anything close to it. But it would be incorrect to suggest that there are no known beneficial interventions.

Perhaps the most convincing example of a clear beneficial effect on recidivism is medication for psychiatric disorders. For example, medication for ADHD and psychotic disorders has been shown to reduce offending in individuals with the relevant diagnoses (Lichtenstein et al., 2012; Sariaslan et al., 2022; Ceraso et al., 2020).

Unfortunately, the reality is that there is no known intervention which can be broadly applied to great effect, ultimately producing a large effect at the national level. If such interventions were known, they would be used. There are, of course, other hypothesized interventions and studies of their effectiveness. But the evidence is often weak and suffers from publication bias. Well-evidenced and powerful interventions are usually only applicable in specific circumstances (like medication for psychiatric disorders), and would thus only have modest effects on national recidivism rates.

Conclusion

The idea that the Nordic countries have achieved remarkably low recidivism rates is a misconception. In Denmark, Sweden and Finland, about 1 in 3 of released prisoners will commit a crime leading to a new conviction already within 2 years of being released. Over a longer period, the majority will at least be rearrested. Even in the best example, Norway, about 1 in 5 will be be convicted for a new crime committed within just 2 years after being released. However much the Nordics focus on rehabilitation, there is clearly a large group of people for whom they cannot prevent reoffending.

How does the United States look in comparison? Comparing recidivism rates between countries is challenging, and when large differences are observed, one should be suspicious that they are not equivalently measured. If we make the comparison as close to apples-to-apples as we can, the American recidivism rate is very close to that of Denmark, Sweden and Finland. When one considers how much more criminal the United States, their recidivism rate is, if anything, surprisingly low. I have speculated that the low reconviction rate may even be indicative of under-policing.

Of the countries considered, Norway has the lowest measured recidivism rate. While it is possible Norway’s more rehabilitative approach contributes meaningfully to that, I have argued that much of the disparity can likely be explained by other factors. I have discussed factors relevant specifically to the Norwegian case. But I have also reviewed more general evidence on what influences recidivism rates. The evidence suggests that variation in recidivism rates both between and within countries are greatly affected by factors beyond the prisons. Therefore, it would be a big mistake to conclude that Norway rehabilitates much better simply on the basis of measured recidivism rates.

The things that do reduce recidivism are also often not the same strategies that rehabilitation proponents advocate. Therapy, probably the most commonly suggested intervention these days, is not particularly effective at reducing overall recidivism rates. Interventions that work are likely to be more contextual, and it is unlikely that any intervention, broadly applied, can drastically lower recidivism rates. To think that any intervention(s) could replace prisons any time soon is fantastical.

Ragnar Kristoffersen — one of the principal researchers involved in the comparative research on Nordic recidivism rates — makes an important point. We must distinguish between the ethical question and the descriptive question; that is, (a) how we think prisoners ought to be treated, versus (b) what effectively reduces recidivism in practice. Regarding the idea that “treating people nicely will keep them from committing new crimes,” he says that there is “very poor evidence” (Benko, 2015). Yet he still believes we should do so out of ethical considerations.

The definition of each recidivism measure is given in Durose et al. (2014), p. 14-15. “Return to prison” includes when “when the offender was returned to prison without a new conviction because of a technical violation of his or her release, such as failing a drug test or missing an appointment with a parole officer.”

The definition used that led to the Norwegian 20% recidivism figure was: “Relapse is defined as a new prison sentence or community sanction that became legally binding within two years of release from prison or from commencement of the community sanction in 2005. Put differently, suspended sentences and fines are excluded from the relapse definition. Secondly, at least one act of reoffending must have taken place after release from prison or after starting a community sanction in 2005” (Kristoffersen, 2013). The definition used for “incarceration” by Durose et al. (2014) is “Classifies persons as a recidivist when an arrest resulted in a prison or jail sentence.”

According to SpeedingEurope, “Norway is the only European country who regularly condemns its citizens to prison sentences for speeds that seem perfectly natural for citizens of other European countries. 150 km/h on a motor road under perfect conditions is enough to land you in jail for at least 18 days – unconditionally.”

As far as I am aware, there is no publicly available data that allows us to calculate exactly what the recidivism rate is when deportees are excluded. We can, however, make some very rough estimates to get a sense of a realistic range of effect it could have in practice. Suppose that one fifth to two fifths of those ever imprisoned are foreigners, that one third to two thirds of foreign prisoners are deported, and finally that half to three quarters of deported criminals do not return to the country (and thus cannot recidivate). Then the recidivism rate, excluding deportees, could increase by a factor of 1.03 to 1.25. In other words, the 20% figure could move to 20.7%-25%. And excluding both deportees and traffic crime, the 25% figure could move to 25.9%-31.3%.

Kristoffersen (2022) provides recidivism rates from the Nordic countries for prisoners released 2016-2020. Figures are given in section 2.11. For this comparative research, scholars have gone through great efforts to use as comparable definitions as possible. Data on reconviction within a 2-year time frame is provided. To reduce year-to-year noise, I have used the aggregate values across the entire 2016-2020 period.

For American recidivism data, I rely on the BJS analysis by Durose & Antenangeli (July, 2021), which follows prisoners released in 2012 across 34 states for up to 5 years. The 2-year reconviction rate can be found in Table 7.

In addition to the already discussed facts about Norway, Kristoffersen (2022) notes that: “A national police reform reducing the number of organizational police unities was introduced in 2017, followed by fewer prison sentences. This may have influenced the reconviction rate as well.” The reconviction rate went from 23.0% (2014-2016) to 18.2% (2017-2018).

Great piece. I’d assign it if I was still teaching courses on Crime Policy

My only issue, while the age variable is mentioned, I think it explains more than the article implies.

If we look at age specific crime rates we can see that most crime is committed by younger people. The curve is quite steep until about age 24 (the last time I looked) and then drops for most crimes. Wherever there is reliable data cross culturally, we see the same basic pattern. While this is less clear for expressive crime, the modal category is still below 25. So if Norway, because it has relatively short sentences probably releases many more people in their 20’s, has this low a recidivism rate, something must be going on.

Maybe age is the most effective type of rehabilitation?

For those of us who do not like sentencing and prison policy in the US it is troubling that we see the uncomfortable fact that because of the age variable the longer people stay in prison, the less likely they are to commit serious violence crimes after being released. If the age of prisoners released in Norway is much lower than in the US, all other things being equal, we should expect a much higher recidivism rate.

I doubt this can be explained by what happens in prison. I'd rather look at what kinds of supports there are for inmates when they leave prison

Another difference is that in the US is perceived rehabilitation and behavior in prison can often impact the length of a sentence, while in the Scandinavian model perceived rehabilitation is more likely to impact the level of custody rather than the length of a sentence. Declining levels of custody and partial release may be making the transition back into society more effective places like Norway. There is evidence that for substance abuse offenders it appears that what happens in that transition period has a great impact on recidivism than what goes on on a prison setting.

I doubt what happens in prison determines the differences in recidivism rates. Because age explains so much about offense rates, comparing recidivism by age cohort would probably tell us more about how system compare and what works and what does not.

again a thought provoking article

I was just having a related discussion with somebody last week. I read an article about the Nordic prison model and their alleged success with rehabilitation, and I was suspicious. Looks like my suspicion was warranted.

This is a fantastic breakdown - you made the facts clear and easy to understand.