The Dark Ages

A quantitative assessment of Europe's decline, slumber and awakening

Introduction

The ancient Roman Empire once controlled most of Europe. But their greatness extended beyond territorial control and military capability—they were global leaders in the intellectual and cultural domains.

As the Empire declined, it left a vacuum in the European continent. Roman trade networks broke down, knowledge was forgotten, literacy rates fell, and high culture declined. The period in Europe lasting from the late 5th century to the 10th century AD is called the Early Middle Ages, but is colloquially known as The Dark Ages.

The aim of this post is to make a quantitative assessment of this period in European history. First, the fall of the Roman Empire will be analyzed. Second, we will consider the rise of the Frankish kingdoms, representing an important step in Europe’s awakening. Lastly, we will consider just how “dark” the Dark Ages really were — in terms of written works, notable scholars and technological innovation and adoption.

Modern historians dislike the term “Dark Ages”.1 It is one thing to reject the terminology on the grounds of it being too reductive and misleading. It’s an entirely different thing to deny the decline wholesale. A reasonable case can be made for the former, but not the latter. In this piece, the Early Middle Ages and the “Dark Ages” will be used interchangeably.

The Early Middle Ages were by no means an intellectual void. But caricatures notwithstanding, this period in Europe was characterized by marked economic, cultural and intellectual decline, at least when compared to the greatness that was the Roman Empire.

Content

The Roman collapse

Economic and civilizational decline

Intellectual and cultural decline

Europe’s nadir (6th-7th centuries)

The Rise of the Franks

How “dark” were the Dark Ages?

Written works of the Dark Ages

Scholars of the Dark Ages

Technology of the Dark Ages

Summary

Light at the end of the tunnel: 10th-13th century

The Roman collapse

The Roman Empire reached its maximum extent in 117 AD, and the two-century period between 27 BC and 180 AD — “Pax Romana” — is considered the golden age of Roman imperialism and expansion. But, as we all know today, it wouldn’t last forever. The Empire would eventually decline, and the reasons why are widely debated to this day.2

The consequences of the disintegration of the Empire have been well-summarized elsewhere (Hellemans & Bunch, 1991):

“The fall of the Roman Empire was followed by the extinction of the administrative and military infrastructure that had been established throughout Western Europe by the Romans. Roads, bridges, and water-supply systems built by the Romans fell into disrepair, postal services ceased, the use of currency became replaced by barter, and agricultural production diminished considerably. Trade almost stopped entirely, and people relied on the local production of food and goods.”

But before analyzing the state of post-collapse Europe, let us first briefly consider the timeline of the decline itself.

Economic and civilizational decline

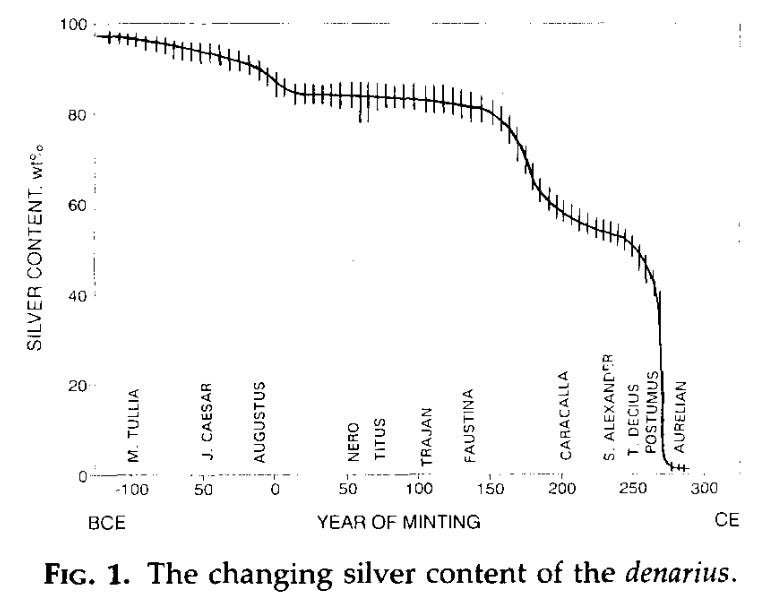

The economic decline of the Roman Empire can be observed from the debasement of the their silver coin currency (the denarius), which decreased in both size and silver purity across the society’s lifespan.

There is a gradual and minor decline in the first few centuries. But between 165 and 180 AD, the Roman Empire was ravaged by the destructive Antonine plague. This coincides with a negative shock in the denarius fineness (McConnell et al., 2018).

The empire nearly collapsed during the Imperial Crisis (235-285). Starting with the assassination of Severus Alexander, it was a period that saw barbarian invasions and political instability in the form of peasant rebellions, civil wars and usurpers competing for power. The economy declined markedly as trade networks broke down and the denarius debased further.

In light of the Crisis of the Third Century, it was considered impossible for a single emperor to govern the empire. The empire was divided into a Western and an Eastern part, each ruled by separate emperors. Though the East-West distinction only briefly existed officially, a de facto separation existed in various periods intermittently between the 3rd and 5th centuries.

When the emperor Theodosius I died in 395, the extent of the Western Roman Empire was still substantial, but, having survived two civil wars, the Empire inherited a weakened military. Facing further pressures from outsiders, the territory of the Western Roman Empire collapsed entirely in the 5th century.

The Eastern Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire3, endured for centuries after. However, considering their territory mostly covered today’s Turkey and some parts of Southeastern Europe, Western Europe was no longer under significant Roman control.

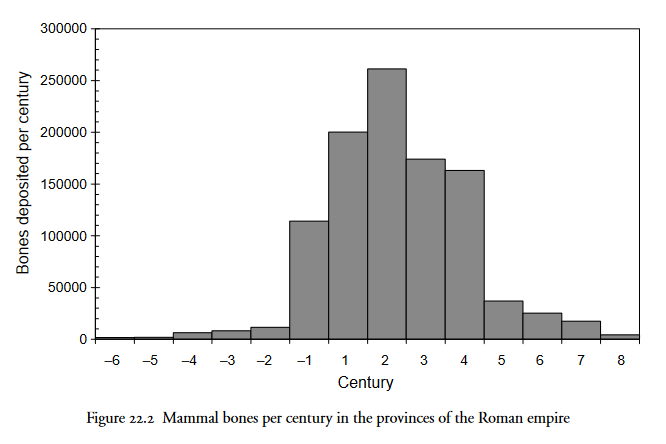

Following the collapse, European civilization experienced a great setback. This can be quantified in numerous ways (see, e.g., Jongman et al., 2019). The population in Europe fell substantially, and along with it urbanization rates. Living standards also seem to have fallen.

For example, Roman animal bone remains have been analyzed as a proxy for meat consumption (Jongman, 2007). The data shows a collapse in consumption from the 4th to the 5th century. Similar patterns are seen for other indicators of consumption, such as fish salting installations (Wilson, 2006).

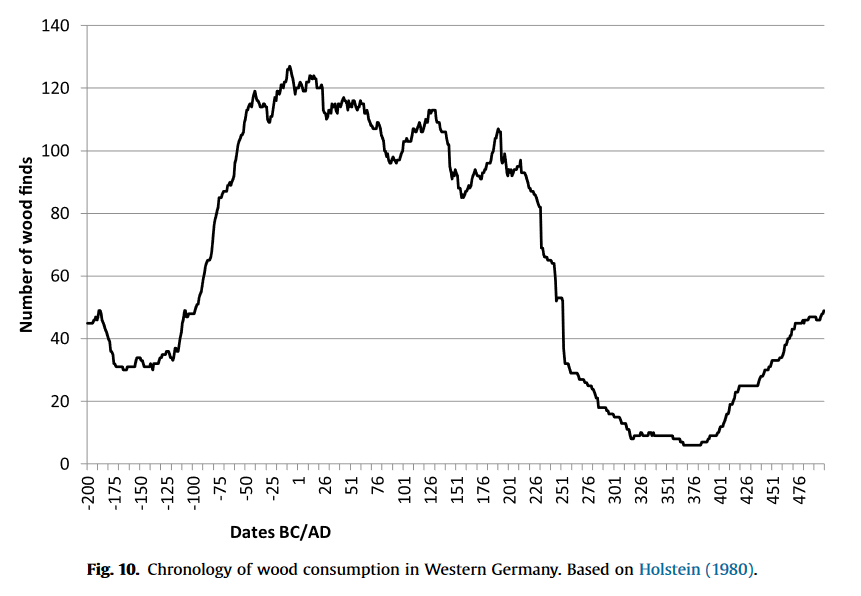

As an indication of housing, a chronology of building wood finds in Western Germany illustrates a decline in the 3rd century (based on data from Ernst Hollstein, 1980).

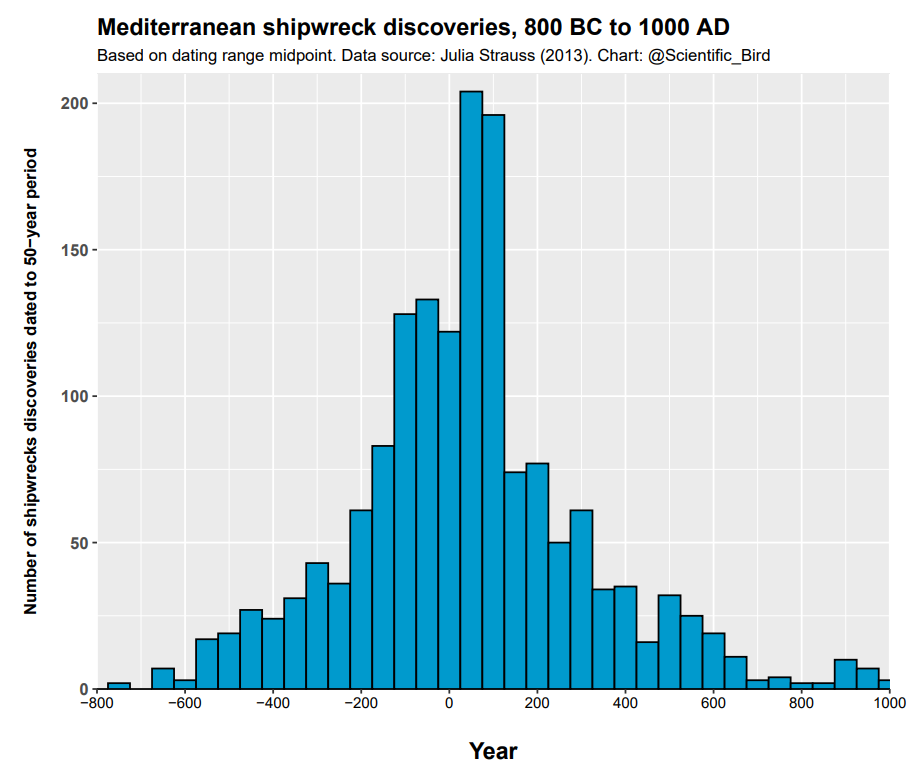

An important aspect of the Ancient Roman economy was maritime trade. Dated shipwreck discoveries have been used as an indicator of maritime activity. We see a large reduction in Mediterranean shipwreck discoveries with the decline of the Roman Empire (Wilson, 2011). In particular, there is significant decline from the peak in the 1st century to the 2nd century.

Wilson (2011) points out an important caveat, however. In the Middle Ages, the container of choice changed from clay amphorae to wooden barrels. Since shipwrecks are typically discovered from cargo remains on the ocean floor, and wooden barrels are highly perishable, medieval maritime activity is underestimated from this data. Even shipwrecks discoveries dated to the Renaissance are relatively few, indicative of how serious this issue is. Still, the large decline occurring within the Roman period is difficult to explain in any way other than as a real indication of a significant drop in maritime activity.

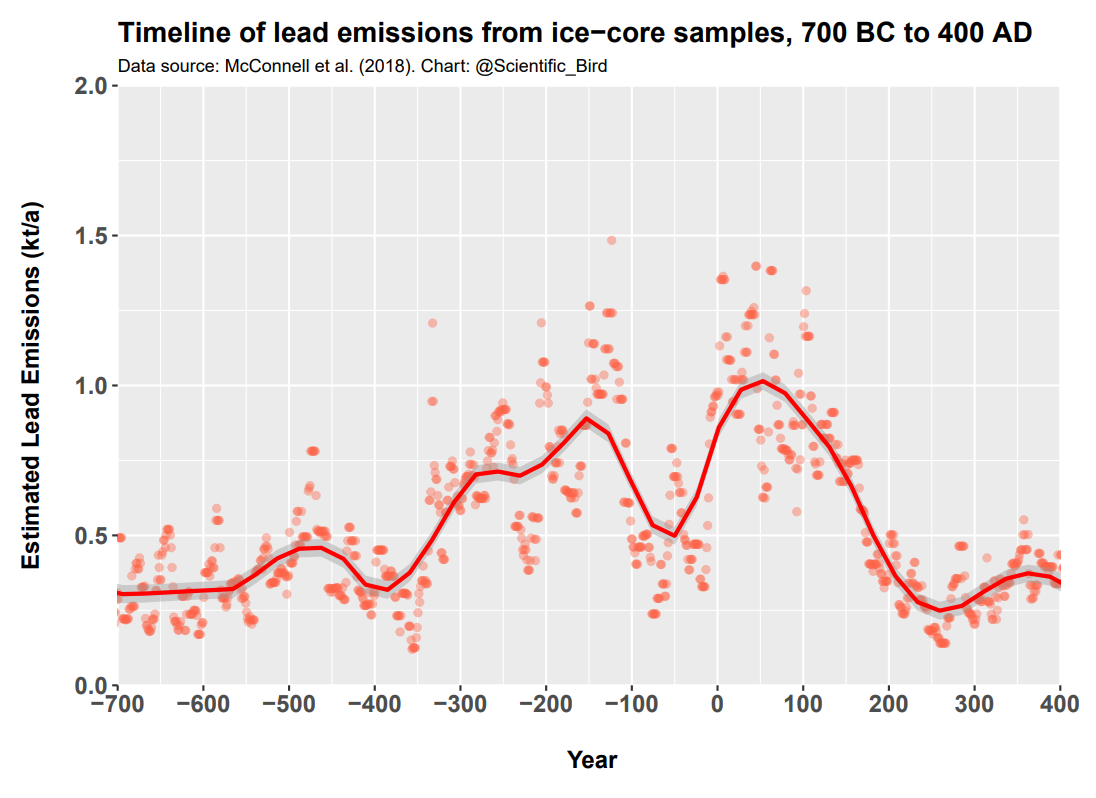

Societal trends can also be inferred from analyzing lead pollution from ice-core samples (McConnell et al., 2018; Loveluck et al., 2018). Emissions from ancient lead/silver mining and smelting produced lead pollution, and are therefore indicative of economic trends. Results from such measurements are shown below.

There is a distinct Roman peak in the 1st century. This is followed by a decline in lead emissions, at the same time the denarius is also having its silver purity reduced. This suggests a great economic decline, with the most rapid decline coinciding with the Antonine plague, 165 to 180 AD (McConnell et al., 2018).

In summary, the economic decline can be observed by the following (approximately) simultaneous trends: (1) the debasement of the currency, (2) the drop in maritime activity, (3) and from lead pollution data, indicating less mining.

Intellectual and cultural decline

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Patterns in Humanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.