Race, economics and homicide in the United States: a summary

Why economic factors cannot explain homicide disparities in the United States

Introduction

It is well known that the national American homicide rate is uniquely high among the most developed countries. However, the homicide perpetration and victimization risks are far from equally distributed. In particular, homicide rates are much higher for black Americans.

But black Americans also tend to be economically worse off than other large groups in the country. A central question in American criminology is to what extent these homicide disparities can be accounted for by the causal effects of these non-trivial economic disparities. This post tackles this question, one step at a time.

First, I analyze to what extent geographical differences in homicide rates within the United States correlate with demographic and economic variables. Second, I analyze whether group disparities persist when you compare people who are similarly economically situated. Finally, I discuss how these results should be interpreted in terms of causality.

Correlates of homicide

To begin to address this question, the simplest approach is to use a traditional regression analysis. I consider a large dataset of virtually all >3,000 counties in the United States, and their homicide rates between 2018 and 2021. I combined this with county-level demographic data and several economic variables (measured through the American Community Survey).

I created three regression models: a purely economic model (1), a purely demographic model (2), and a model that combines economic and demographic variables (3). The results are shown in the table below.

The table should be read as follows. In model (1) it is found that one standard deviation difference in county poverty-level is associated with a β = 0.46 standard deviation difference in homicide rates, or 1 percentage point difference in poverty rate is associated with a difference of b = 0.50 homicides per 100,000. Similarly, the demographic model (2) says that a standard deviation difference in county black share is associated with β = 0.81 standard deviation difference in homicide rate, or 1 percentage point difference in county black share is associated with b = 0.37 more homicides per 100,000.

The results show that the model using socioeconomic factors (1) explains 31.4% of the geographical variation in homicide rates, whereas the model that used only racial/ethnic demographic factors (2) explains a whole 60.8%. Demographic factors therefore explain nearly twice as much variation in homicide rates as economic factors do.

When the socioeconomic factors and racial/ethnic demographics are combined into a single model (3), it explains 65.4% of the variation in homicide rates. In this model, both economic and demographic factors remain significantly related to county homicide rates. However, racial/ethnic demographic variables (in particular, black share) have substantially more explanatory power than the economic factors. The total 65.4 percent variance explained by model (3) can be decomposed into 42.9 percentage points explained by demographics and 22.5 percentage points explained by the set of socioeconomic factors.1

In short, racial/ethnic demographic variables are substantially more predictive of county-level homicide rates than economic factors. And, as I will discuss later, we cannot interpret what’s “explained” by economic factors as a demonstration of a causal economic effect on violent crime.

Economics and group disparities

In light of the previous findings, it would seem unlikely that homicide disparities could be fully explained by economic factors. Indeed, this is what I found in a previous piece, where I investigated precisely this question. I disaggregated economic factors and homicide by race/ethnicity, such that we could compare homicide rates for people in similar economic standing.

I first showed that, even in theory, it is not possible that poverty could fully account for the homicide disparity. This is because, while black people are overrepresented among the poor, they are not sufficiently overrepresented to possibly explain the gap. Empirically, I found that the black-white homicide gap shrinks only about three tenths when you adjust for economic differences.

The figure below shows the homicide victimization rate by race/ethnicity at various income-levels. Large homicide gaps remain at any income-level. Furthermore, I repeated the analysis for several other economic indicators, and the results were robust.

Note that these findings are not explained by the use of victimization rather than offending rates. As I explain in the piece, due to interracial homicides, the disparities for homicide offending rates would be larger than that of victimization rates, not smaller.

Interpreting the poverty-violence association

Two primary conclusions arose out the previous sections. First, homicide rates are more strongly associated with racial/ethnic composition than economic indicators, however economic correlates with homicide rates are still significant and non-trivial. Second, when we compare people who are similarly economically situated, large disparities in homicide rates remain. However, again, the adjusted disparities were a little smaller than unadjusted disparities.

These findings may naturally lead one to conclude that, though economic disparities are far from a full explanation of the racial/ethnic homicide rate disparities, they are nevertheless important contributors. But even this conclusion would be premature.

It is clear that violent crime is correlated with poverty. This, however, does not mean that violent crime is the result of poverty. In fact, we have actively good reasons to believe that the correlation is mainly driven by other factors. In yet another previous piece, I discuss and substantiate these points in greater detail.

Poverty and violent crime could be correlated due to three reasons: (1) poverty causes violent crime, (2) crime causes poverty, or (3) common causes influence propensity for both poverty and crime. I argued in the piece that the latter two points — reverse causality and especially selection — are the primary reasons why poverty and violent crime are correlated. Below I give a brief discussion of each of these three possible contributors.

Causality

In the previous piece, I reviewed several strains of causally informative evidence regarding the supposed economic influence on violent crime perpetration.

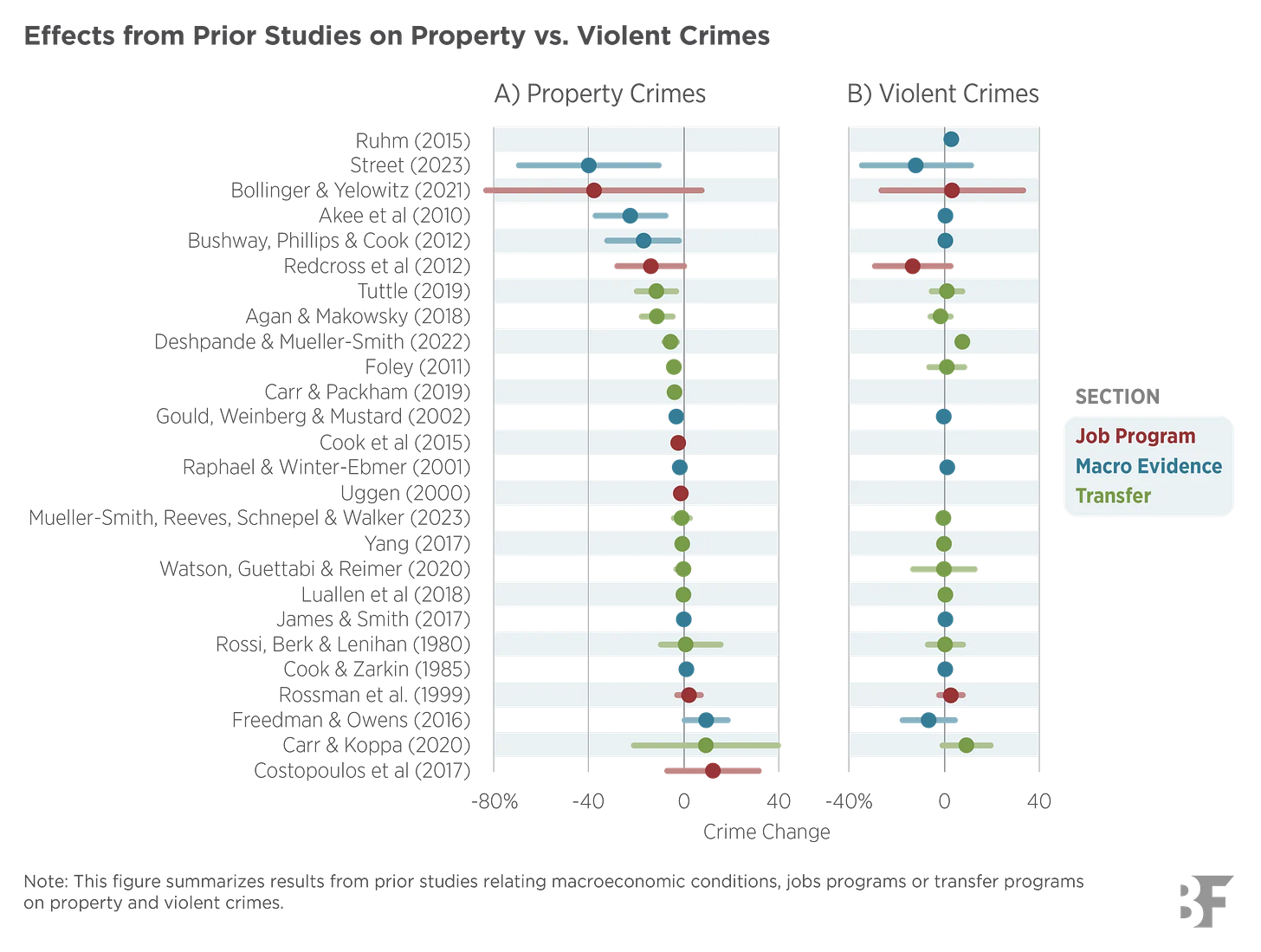

This review included: (1) sibling discordant studies, in which siblings exposed to different socioeconomic environments are tested for discordance in violent crime perpetration; (2) within-individual studies, in which socioeconomic changes within a person’s lifespan is tested for associations with crime changes; (3) evidence from income-transfer and jobs programs, (4) macroeconomic evidence, and (5) other miscellaneous studies such as welfare payment cycle and lottery studies.2

Consistent from all these more causally informative lines of evidence is the conclusion that poverty has little to no causal effect on violent crime. No line of evidence is by itself conclusive or immune from plausibly sounding critiques but, all evidence considered together, we can be fairly confident in this conclusion.

If poverty has little causal influence on violent perpetration, how can we explain their systematic association? Reverse causality and (more importantly) selection.

Reverse causality

Crime causes poverty. As I show in the piece, this can be observed at the individual-level and the group-level. Namely, when a person commits a crime, it hurts their employment prospects and income, at least in the short term (Agan et al., 2023; Brown, 2018). Further, and perhaps more importantly, crime has a negative impact on the economy at the community-level (e.g., Donovan et al., 2024; Cullen & Levitt, 1999). This deleterious influence occurs in a direct way, by impeding local businesses, and indirectly by making productive people selectively migrate to safer neighborhoods.

Selection

Traits like cognitive ability, personality, mental disorders, substance abuse, and likely many more, influence both economic outcomes and criminal outcomes.

As a result of social mobility, the traits that result in both lower economic productivity and are risk factors for violent crime become less frequent among the higher classes, and more frequent in the lower classes. Constant selective mobility and intergenerational transmission together ensure that persistent differences in various traits can be maintained between social classes.

Any racial group contains substantial individual variation in economically and criminally relevant characteristics. And, within any racial group, economically successful individuals will, as a group, have a lower concentration of the characteristics that are risk factors for violent crime (e.g., low cognitive ability, mental disorders, anti-social personality traits), and the poorer ones will have them in higher concentration.

Economic correlates of homicide may simply be “absorbing” these underlying relevant individual differences and serve as proxy for them. And, similarly, when we compare people who are similarly economically situated, we are not just observing the consequence of equalizing economics, but also partly the equalization of these underlying individual differences.

This is why economic correlates or “controlling for economic variables” cannot simply be interpreted as measures of the causal economic effects. The takeaway is that adjusting for economic disparities provide us an upper bound on the importance of the economic disparities.

Conclusion

Regression results show that, while both racial/ethnic demographic and economic factors statistically “explain” variation in homicide rates in the United States, demographic factors are substantially more explanatory. Similarly, when we compare people who are similarly economically situated, large black-white disparities in homicide rate persist.

Evidence from causally informative research shows that the causal economic effect on violent crime is marginal or null. While poverty and violent crime are correlated, this is mainly the result of selection (and reverse causality). Because of this, adjustments for socioeconomic disparities will exaggerate the (causal) importance of those socioeconomic differences.

These points considered together, racial/ethnic homicide disparities have, at best, a weak causal connection to economic disparities. If economic disparities were fully removed by an economic intervention, the homicide gap would remain mostly intact.

To calculate the “partial” R-squared values, I used the R-package “relaimpo” (Relative Importance of Regressors in Linear Models). The setting was type = “lmg”, otherwise default modes.

My piece on the causal nature of poverty on violent crime discusses the evidence in much greater detail. However, a recent review by Ludwig & Schnepel (2024) comes to a similar conclusion that there is little to no systematic economic effect on violent crime.

The evidence I cite includes sibling studies (e.g., Sariaslan et al., 2021; Sariaslan et al., 2013); within-individual studies (e.g., Airaksinen et al., 2021); evidence from income-transfer and jobs programs and macroeconomic evidence (see Ludwig & Schnepel, 2024); welfare payment cycle studies (e.g., Stam et al., 2024); and lottery studies (e.g., Cesarini et al., 2023).

Good write-up. There's also this prior write-up and collection of more of those regression studies. This includes one also on counties with more socioeconomic variables.

https://archive.ph/v5WEX (orig. https://thealternativehypothesis.org/index.php/2016/04/15/race-poverty-and-crime/)

I'd be interested in side by side maps for homicide rates and population density, also rates over time. Would I be correct to assume there are rural places where even a single murder is enough to put you in the red/black because the population is so low? Is what we read ... that homicide in the USA is largely an urban affair ... true?