Prisons aren't filled with harmless pot smokers

The American incarceration rate explained

Introduction

A common belief is that U.S. prisons are filled with offenders of victimless or trivial crime—imprisoned merely for being in possession of weed for personal use, or perhaps driving under the influence without accident, et cetera. At its most extreme, this belief gets you books like “The New Jim Crow.”

The U.S. prisoner count is the usual starting point of this argument—which, indeed, is high. With 541 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants, the American prisoner rate ranks 5th in the world, only beaten by a handful of less developed countries. Owing to its large population size and high prisoner rate, the U.S. has more prisoners than any other country. As I recently pointed out, the fraction of men who receive a prison sentence in their lifetime is non-negligible.

Yet this belief remains false. Despite the high prisoner count, American prisons are not filled with people who committed innocuous offenses. The modal prison inmate has a long criminal record and is guilty of violent crime.

I will substantiate these points, and then I’ll provide context for the high American incarceration rate.

Prisoners have committed serious offenses

Prison population composition

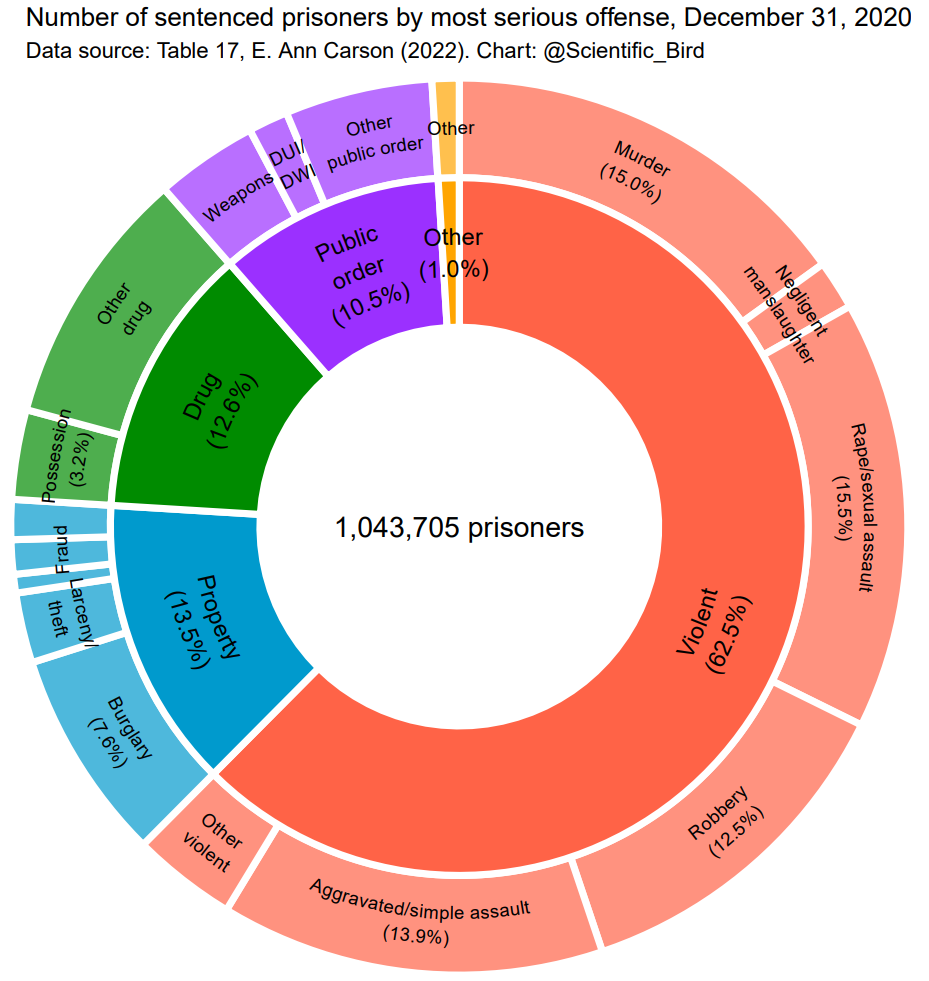

To address this question, we can simply look at the prison population categorized by their most serious offense (Carson, 2022):

The data dispel the notion that the prisoner rate is high because countless people are imprisoned for trivial offenses. A clear majority of prisoners have committed violent crime (62.5%). Nearly five times as many prisoners are in for murder compared to drug possession (15.0% vs 3.2%).

Even non-violent offenses tend to be serious. Burglary comprises over half of the property offenses. Drug possession only accounts for a small fraction of drug crimes and just 3.2% of all inmates—and even this figure should be interpreted in the light of possible plea bargains.

This shouldn’t really be surprising. After all, prisons (as opposed to jails) are designed for long-term incarceration. Jails are where people are held while awaiting trial or sentence, or while serving short sentences.

Prison admissions

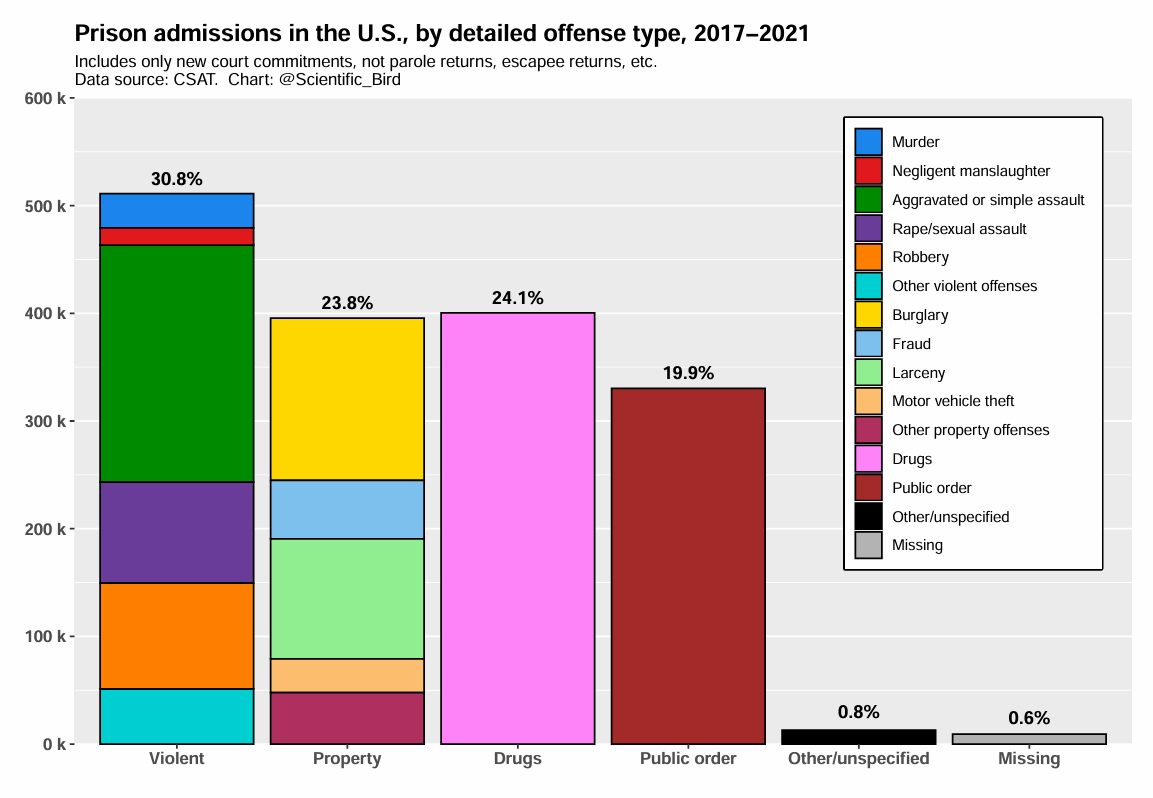

There’s a distinction between the prisoner composition, and the composition of prison admissions. People enter and exit prisons every day, and those with shorter sentences leave more quickly.

The composition of the prison population is therefore a function of both admissions and sentence length—it will be skewed towards more serious crimes with longer sentences.

Yet, even when we look at prison admissions, a plurality (but not a majority) have committed violent offenses:

Unfortunately the available admission data do not allow me to break down drug or public order offenses into more detailed categories. However, recall that drug possession and DUIs account for only small proportions of their respective categories (drug crimes, public order crimes) in the prison population.1

Prisoners are repeat offenders

Prisoners have not only typically committed serious offenses, they have also typically committed many offenses.

The figure below shows the number of prior arrests for people admitted to state prison (including the arrest that led to the prison sentence).

The median number of prior arrests was nine. More than three quarters have at least 5 prior arrests. Having 30+ prior arrests was more common than having no arrest other than the arrest that led to the prison sentence (i.e., 1 prior arrest).

It should go without saying that those imprisoned with no prior arrests have usually committed highly serious offenses that would warrant imprisonment with no prior criminal record.

Prisoners have committed more crime than records suggest

As striking as these figures are, they still understate prisoners’ criminal histories. This is because of the dark figure of crime—the amount of unreported, undetected, or undiscovered crime (Biderman & Reiss, 1967).

A highly replicated finding is that criminals self-report having committed many offenses for each police contact. That is, they readily admit to having “gotten away with” many offenses.

One study of 411 males found that the self-reported number of offenses was over 30 times greater than convictions (Farrington et al., 2014). For sexual offending, studies have estimated the dark figure to be anywhere from 6.5 to 20 times the official figure (Drury et al., 2020). In a recent study of American delinquent youths, the self-reported number of delinquent offenses was 25 for every police contact (Minkler et al., 2022).

However large the dark figure of crime exactly is, it is undoubtedly practically significant. Prisoners’ criminal histories are therefore substantially more extensive than their criminal records would suggest.

Why is the U.S. prisoner rate so high?

It is true that the U.S. prisoner rate is very high. But why?

As we’ve just seen, this is not because prisons are filled with people guilty of one or two insignificant offenses. Prisoners are overwhelmingly repeat offenders, and the bulk of them have committed violent offenses. In fact, violent offenses are so predominant that, if all non-violent offenders were released from American prisons, the U.S. would still have a higher prisoner rate than most highly developed countries. Even the Prison Policy Initiative—an advocacy group against mass incarceration—recognizes this.

The real answer lies in a combination unique to the United States: high development and capacity, high rate of serious crime for its development, and longer sentences.

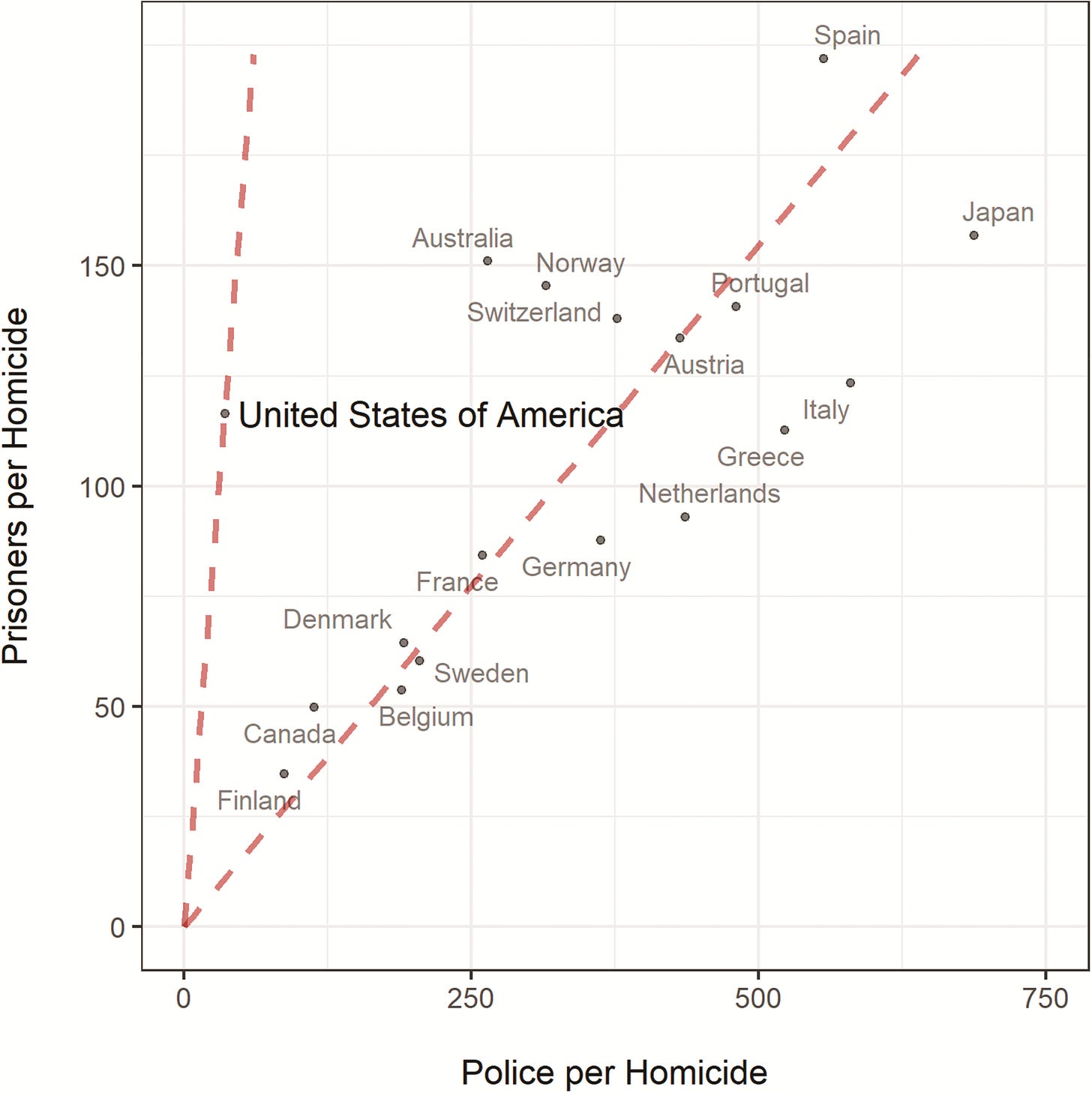

Compared with other highly developed nations, the United States has a much higher rate of serious crime (e.g., homicide). The high prisoner rate is a direct result of that. If we benchmark the prisoner numbers on a per-homicide basis, rather than a usual per-capita basis, the U.S. has a typical number of prisoners and an exceptionally low number of police.2

Globally there are obviously many countries with much higher homicide rates than the United States. But these countries tend to be underdeveloped and do not have the same capacity to fight crime—thus they have lower imprisonment rates. In many third world countries, crime runs rampant and law enforcement lacks the means to properly combat it. The U.S. is rather unusual in its combination of high crime and high capacity.

Lastly, the U.S. has longer prison sentences than other highly developed countries. For example, in a previous post I noted that:

Whereas prison sentences are typically more than one year in the United States, the modal length of an unsuspended prison sentence is one to two months in Denmark (StatBank, STRAF47). This leads to a much larger share of American people being imprisoned at any given time.

Many will naturally have one of two follow-up questions: (1) but why is the U.S. rate of serious violent crime so high? (2) Does America’s co-occurrence of high prison rate and high violent crime rate not disprove the notion that prisons reduces crime? To keep this post short and focused, I will address these only superficially.

National crime disparities exist for many reasons, only some of which are directly related to law enforcement: deterrence from police presence (Chalfin & McCrary, 2017), demographics, and likely many others (e.g., culture, gun access).

Even if prisons reduce crime (and they do, mainly through incapacitation), it is not surprising for high crime rates and high incarceration rates to coexist. The question is based on flawed causal thinking. To see the fallacy, we might draw an analogy between incarceration and medication. Incarceration is a direct response to crime, like medication is a treatment against a disease or condition.

People on medication tend to be more ill than those who aren’t on medication, yet this obviously doesn’t disprove that the medication helps alleviate symptoms. Cross-sectional correlations are highly misleading in contexts where the treatment is directly responding to a symptom.

Evidence with better causal identification shows that incapacitation reduces crime (e.g., Buonanno & Raphael, 2013; Vollaard, 2013; Johnson & Raphael, 2012; Levitt, 1996). Crime would therefore be more prevalent in a counterfactual without prisons.

Conclusion

The U.S. prisoner rate is not high because prisons are filled with people who have committed trivial or victimless offenses. The modal prisoner is both a violent and a repeat offender. Due to unrecorded crime, prisoners’ true criminal histories are more extensive than criminal records would suggest.

The high U.S. prisoner rate can primarily be understood by a combination of factors: its high serious crime rate (relative to its development), its high capacity to fight crime, and its long sentences.

Because the prisoner composition is skewed towards more serious offenses than prison admissions, we would expect that more than a quarter of drug offenders to have been admitted for possession. However, it is likely still a minority of drug offense prison admissions. In any case, it remains a small part of all prison admissions.

Note that prison admissions should be interpreted in the light of possible plea bargains. That is, people admitted for drug possession have often committed more serious offenses but plead guilty to the lesser offenses in exchange for the prosecutor to concede a more serious charge.

Lack of police presence is a contributor to the crime rate. Chalfin & McCrary (2017) review the evidence and show that police presence does have a deterrent effect. This effect is causal, as demonstrated by experiments of policing hot spots.

I'd like to know more about the "Aggravated or Simple Assault" category in violent crime.

Simple assault can include punching or even shoving.

I hold the old-fashioned view that men should be able to have a fist fight without the law getting involved.

Good stuff. I wonder what you think of the better arguments I've seen on incarceration causing crime? They either focus on first time offenders or shortening sentences for lower / medium risk offenders. I'll try to dig up the research later, but from what I remember reading there seems to be at least some quality research in this area. That said I've never seen good arguments of good data to support the idea that repeat offenders shouldn't be locked up.

Also, in case anyone is interested, I put together some graphics that compare homicide to incarceration rate across US states and globally. The scatter plots are much like the scatter in this article, but also includes states and most countries

https://theusaindata.pythonanywhere.com/murder_prison