Are women better at jigsaw puzzles?

An analysis of the World Jigsaw Puzzle Championship

Introduction

Jigsaw puzzles have a long history. In the 1760s, the cartographer John Spilsbury sold “dissected maps,” which some credit as being the earliest jigsaw puzzles. But apparently there has been a recent surge in jigsaw popularity. Some YouTube creators have amassed hundreds of thousands of subscribers, and the World Jigsaw Puzzle Championship was held for the first time in 2019.

Upon observing this little community, you’ll immediately notice one thing: there are lots of women. The content creators, their followers, the contestants in the tournaments, are all overwhelmingly women.

There is nothing wrong with this, but it does invite obvious questions. Are women just more interested in jigsaw puzzles? Are they better at solving them?

These questions are relevant to a broader literature about sex differences in cognitive abilities. It is well known, for example, that men perform better on 3d mental rotation tasks on average. One might intuitively have expected the same to be true for jigsaw puzzles.1

There is very little research on the topic of sex differences in jigsaw puzzle solving ability. McGuinness & Morley (1991) found no significant sex difference among small kids. More recently, Kocijan et al. (2017) and Ramirez et al. (2024) found that females performed better among children and young adults, respectively.

This is not a large collection of studies — and the samples are small (recent studies, n = 46 and n = 79, respectively). With this little data, any confident conclusions would be premature.

Enter... The World Jigsaw Puzzle Championship!

The World Jigsaw Puzzle Championship (WJPC) has been held annually since 2019 (skipping 2020 and 2021 due to the epidemic). Participants compete to show who is the fastest at solving jigsaw puzzles.

The tournament is divided into three rounds: qualification rounds (6 groups), semifinals (2 groups) and finals (1 group). Based on their performance, a select number within each group can advance to the next round. The person with the quickest solution in the finalist round ultimately wins the championship.

Data analysis

I gathered the relevant data for participants in the most recent 2024 championship. Unfortunately, participant sex is not officially registered anywhere. Therefore, I manually went through the participant list and identified sex from their names. This process is no doubt prone to error, but I tried (and hopefully managed) to keep the number of coding errors low.

Results

As expected, participants in the WJPC 2024 were overwhelmingly female (79%). Did male competitors underperform? At first glance, it appears so! While the qualifying rounds were 21% male, just 11% of competitors who made it to the finals were male. This difference is highly statistically significant (p < 0.001).

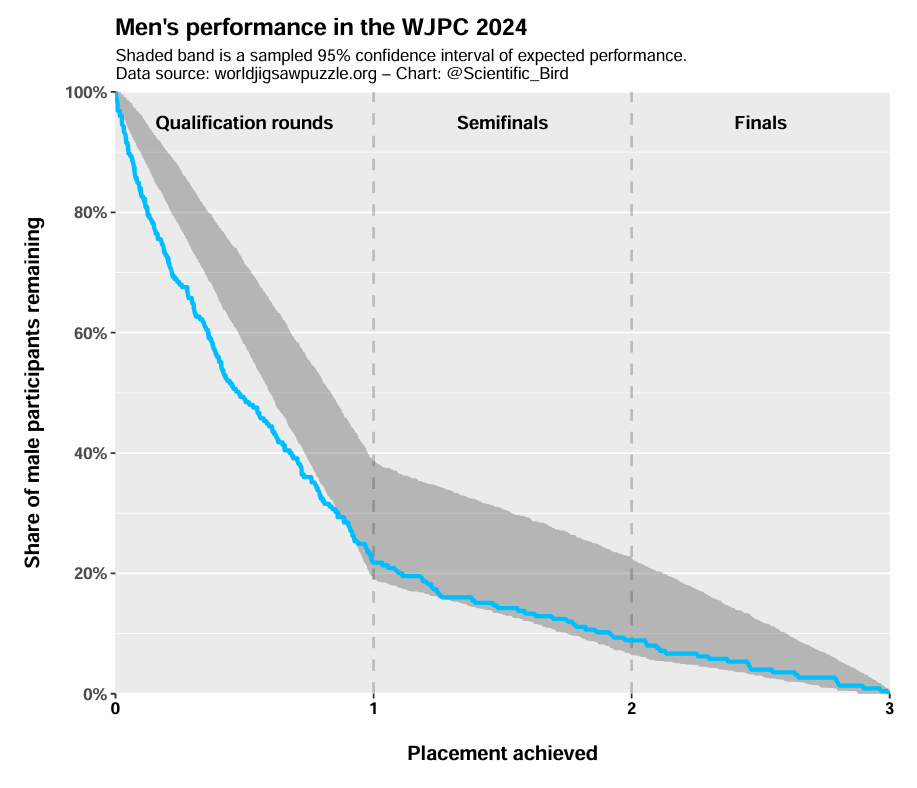

The following figure shows men’s actual performance (blue) compared to expected performance (shaded band) under the null hypothesis of no sex difference. More precisely, it shows the fraction of male participants that reached a given placement in the overall tournament. I labelled it such that 0 to 1 refers to the qualification rounds, and those with rankings just below 1 are those who fell barely short of qualifying for the semifinals. Similarly, placements between 1 and 2 are the semifinals, and between 2 and 3 the finals.

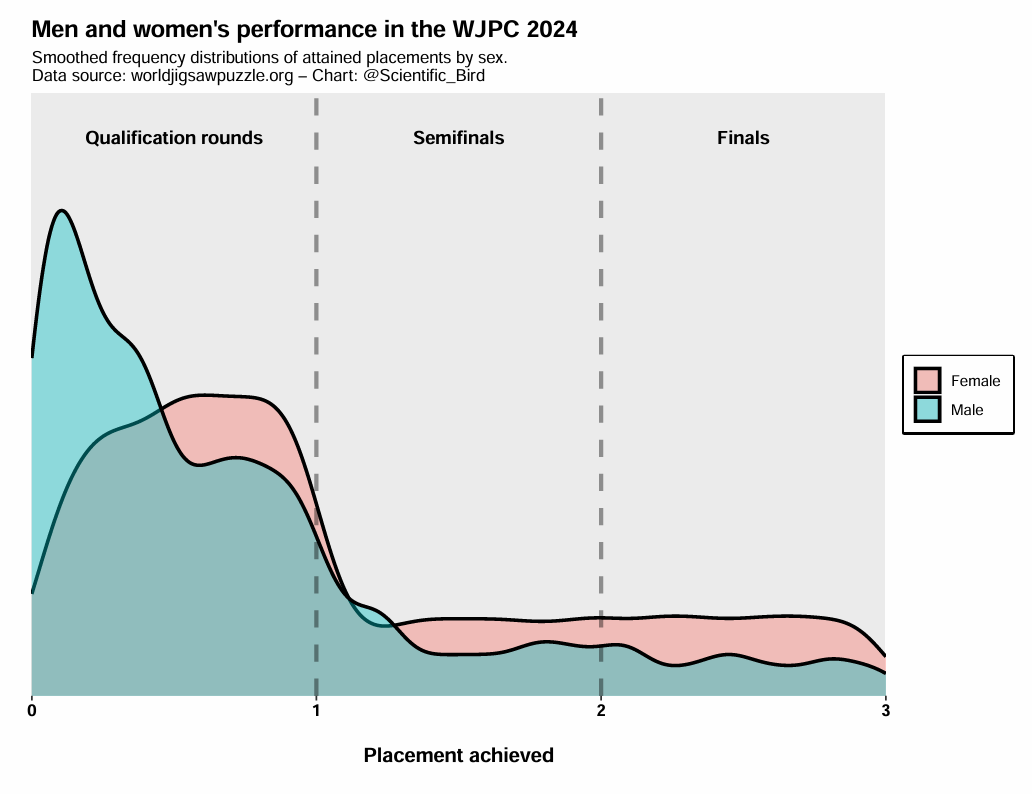

In the qualifying rounds, male participants very clearly (and significantly) underperform relative to expectations. The immediate drop at the start suggests there is an excess of males among the absolute worst performers. This is even easier to see if we plot the frequency distributions of placements attained by sex.

I even noticed this while preparing the raw data. In most qualification groups there was a handful of men clustered near the bottom, but otherwise men’s rankings looked roughly evenly distributed. It seemed odd and looked like a distinct phenomenon to me.

We should keep in mind that, despite it being named the “World Championship”, the WJPC is not just an event for the highly competitive. It is also a casual event for amateurs and other puzzle enthusiasts alike. The 1st place prize is also just €1,000. For all we know, there may be friends, families and/or couples who attend together, even if not all parties participate with serious competition in mind. It’s worth considering if a larger share of the men are casual participants.

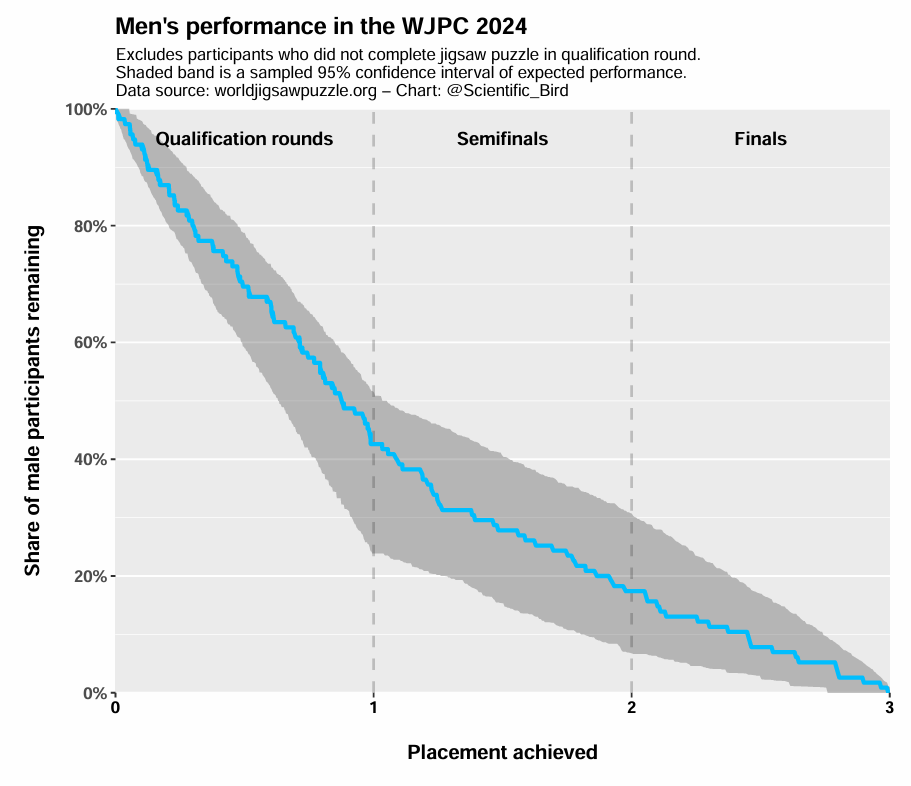

There is no perfect way to distinguish between serious competitors and those who aren’t. Still, I settled on a simple criterion: let’s consider only participants who managed to finish their jigsaw in the qualification round in the allotted time of 90 minutes. This is not a very strict criterion — 69% of participants managed to do so.

What happens to our results if we exclude those who did not finish their puzzle in the qualification round? That’s shown below. In this reduced sample, men perform exactly as you’d expect.

One might object to this analysis in that it artificially removes the worst performers who are disproportionately male, thereby restricting the range in ability. This objection has some merit, but given that the event is partly casual and partly competitive, and the seemingly distinct phenomenon among worst performers, it seemed reasonable to do. Furthermore, 7 out of 10 participants finished their puzzle in time, so it’s not as restrictive as it might sound.

One possible (but speculative) interpretation is that men’s underperformance in the WJPC might be driven a small group of men who aren’t participating with serious competition in mind, who tend to be among the worst performers.

The best of the best

Men are overrepresented at the bottom. Are they therefore also underrepresented among the absolute top performers? Relative to the number of male participants, not really.

The WJPC has been held four times. In two (half) of the championships, the gold medal was won by a man. Out of twelve medals in total, four (a third) were won by men — precisely one each year. This exceeds the male share of participants.

Discussion and conclusion

The overwhelming majority of participants in the World Jigsaw Puzzle Championship are women. The purpose of this post was to analyze whether male participants also perform worse than female participants.

Before addressing that, a short comment must be made. It’s possible that the reason there are fewer male participants is partly because they are worse at jigsaw puzzles. After all, talent inspires interest. If so, comparing male and female participants is slightly unfair towards the women, as the (fewer) male participants would be more selectively drawn from the underlying distribution in ability. Unfortunately, there is no way to account for this.

Do men underperform relative to their number of participants? On average, yes. I find that men are highly overrepresented among the absolute worst performers, and thus attain worse placements on average. However, I do find some suggestive (though admittedly speculative) evidence that this might be driven by a number of male amateur participants. How would the results look if male and female participants were equally determined competitors? We don’t know.

Interestingly, men are far from absent among the absolute top performers. Across the four championships held so far, two of four gold medals and four out of twelve medals have been won by men — greater than the male share of participants.2

So… are women better at speed solving jigsaw puzzles? I lean towards yes. However, rather than providing a clear and definite answer, my analysis has left me with a rather tentative conclusion instead.

What we can say is that, whatever advantage women have, it must be relatively modest. For comparison, consider a game like chess that is instead male-dominated. I think most would say that sex differences in chess ability — to the extent they exist — are relatively modest. Yet in the game’s significantly longer history, no woman has ever been world champion (or even gotten particularly close).3 Men are not equivalently absent from the top in these jigsaw championships.

This analysis obviously cannot say why a difference in jigsaw puzzle solving ability might exist — whether it’s biology, culture, or socialization. Stereotypes suggest that women are better than men at perceiving more subtle color distinctions.4 If this is true, that sounds like a plausible mechanism of a female advantage to me.

Ultimately, this analysis has probably raised more questions than it has resolved. I will leave it to the reader to speculate and form their own conclusions about the questions raised in here.

We should beware of the “jingle fallacy”. Just because jigsaw puzzle solving might be labelled a “visuospatial skill,” or that it bears superficial resemblance to other visuospatial skills, that does not necessarily imply that they tap into the same underlying cognitive abilities.

One possible theory accounting for men’s overrepresentation at the bottom without underrepresentation at the top is to suggest it is a manifestation of greater male variability. At this point, I am not convinced this is actually what is going on. The excess number of men at the bottom looks like a distinct phenomenon to me.

The number of female participants in chess is surely an important contributor, but it’s not a sufficient explanation. Note that the point that differential participation might be partly due to differences in ability also applies here.

From what I can tell, the literature on this question is rather limited and the evidence is not very conclusive.

Male hunters, female gatherers

"There is nothing wrong with this.... obvious questions. Are women just more interested in jigsaw puzzles? Are they better at solving them?"

Imagine any activity or profession where it's mostly men participating and winning.

Can you imagine saying there is nothing wrong with it, and it's probably just because they are smarter at this activity?