Age and infertility

Facts and misconceptions about maternal age-related infertility

The shape of the age-fecundity curve

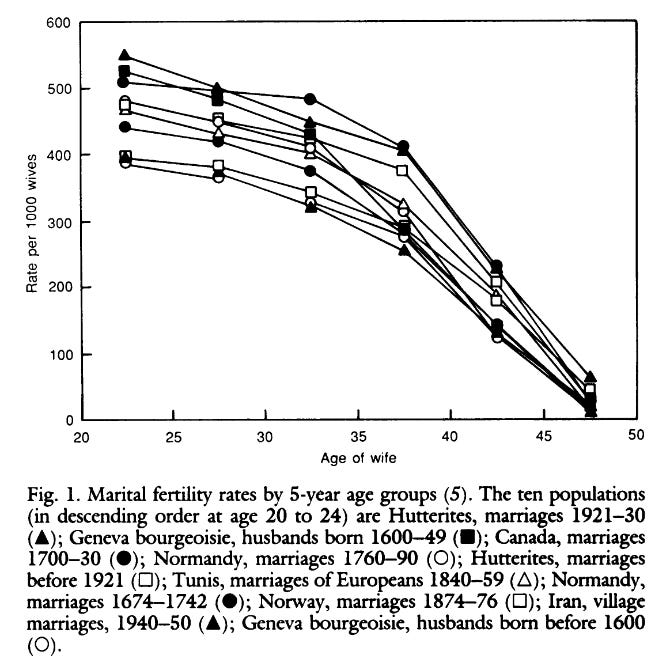

Age is the greatest cause of infertility. But the exact shape of the age-relationship remains contested. It’s widely believed that fecundity begins to rapidly decline in the mid-30s, while any decline in the 20s is comparatively minor (e.g., Menken et al., 1986). This is roughly what I believed until I read an excellent paper by Geruso et al. (2023).

Part of the challenge is what to measure. We typically measure the fertility rate by age. That is, the number of children women have. But the true variable of interest is fecundity, i.e., the potential for childbearing, which is more difficult to measure. If 21-year-old women do not attempt to conceive at the same rate as 31-year-old women, the fertility rate of the latter group may be higher, even if fecundity of the former group is higher.

An additional issue of prior analyses is that months where women are already pregnant (or months of postpartum recovery) have inappropriately been included in the denominator to estimate age-specific fertility rates. The magnitude of this bias is not constant with age.

These issues produce an artificial relationship that is biased relative to the true age-fecundity relationship. In fact, Geruso et al. show that even if the true underlying relationship between age and fecundability is a linear decline, the methods that have been used would artificially produce this concave, accelerating shape.

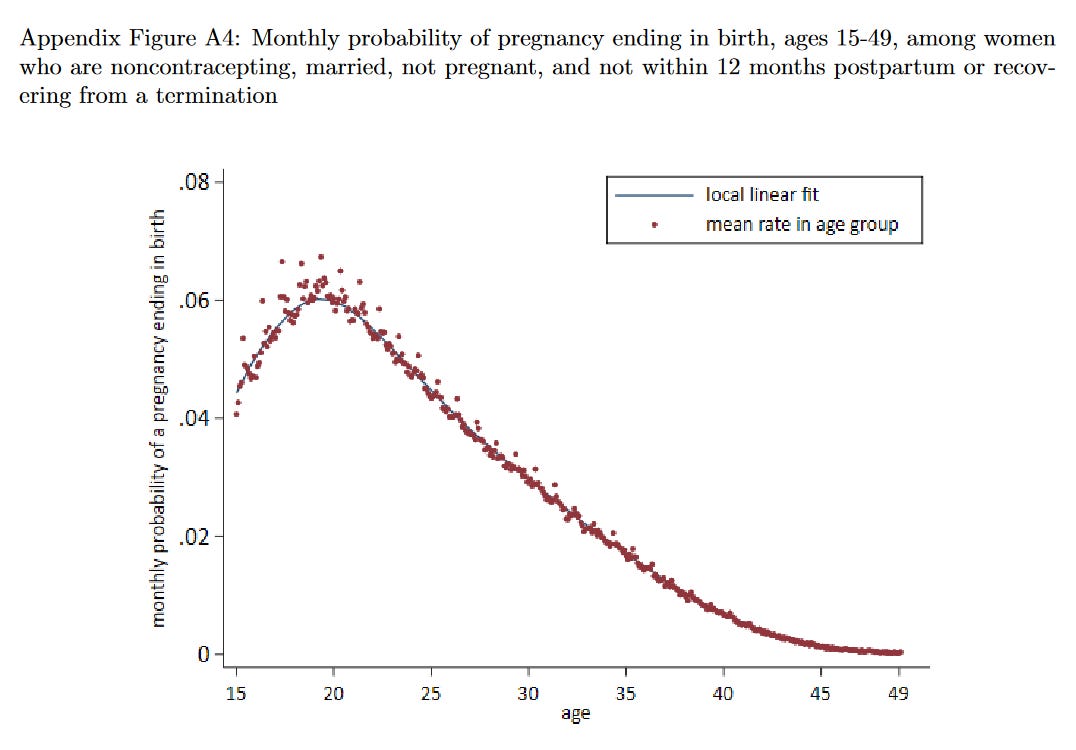

With the aforementioned issues addressed, the authors produce a new set of estimates for the age-fecundity curve, using an impressive dataset totalling 2.8 million women from nationally representative data across 62 countries. Their central result is illustrated below.

As expected, there is a strong (non-monotonic) relationship between age and fecundity. According to their analysis, women’s fecundity peaks when they are aged 19-20 years old.

More importantly, fecundity declines roughly linearly between 20 and 40. Contrary to common belief, there is no sudden accelerating decline in the mid-30s. The drop in fecundity between age 20 and 25 appears no less meaningful than the one between age 35 and 40.

Birth outcomes

Beyond the risk of miscarriage, other health outcomes are also affected by advanced maternal age.

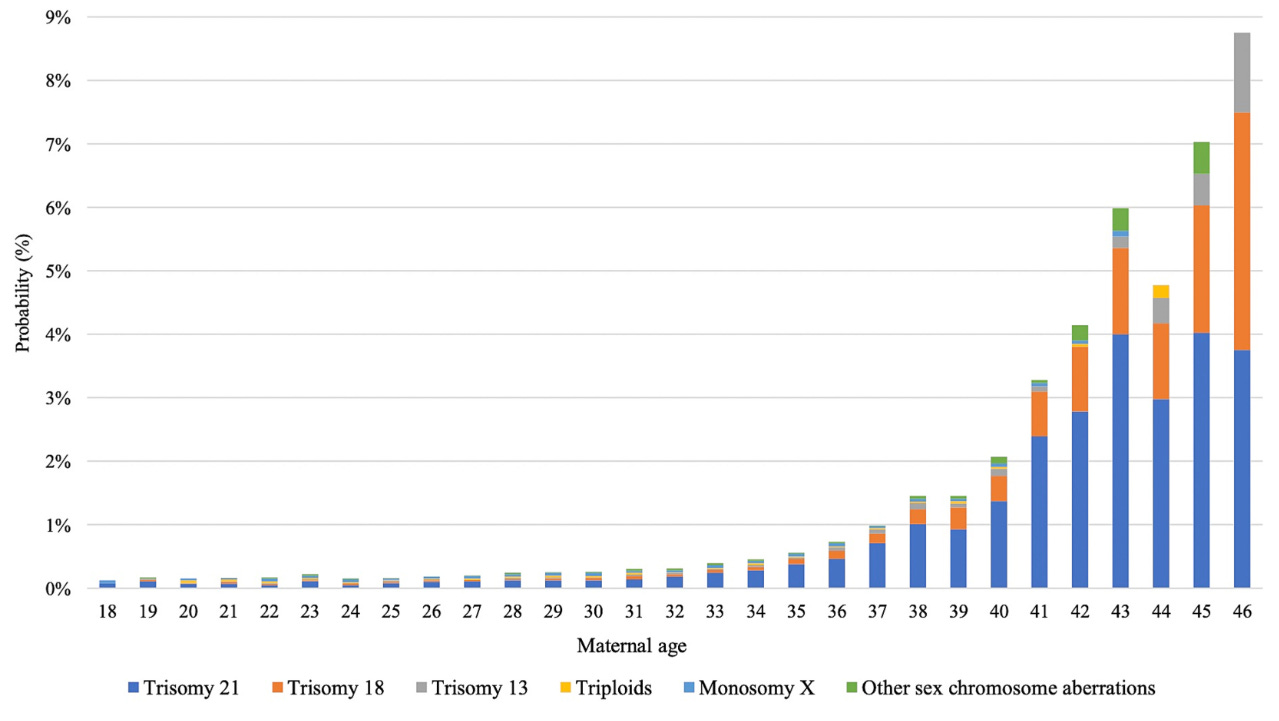

One potential health issue that can arise are genetic disorders resulting from chromosomal abnormalities. While these often result in miscarriage, that is certainly not always the case. The relationship between maternal age and chromosomal abnormalities has been studied in Denmark by Frederiksen et al. (2024). They find that the frequencies of trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) and trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome) all increase greatly with maternal age. Down syndrome, in particular, is surprisingly common when maternal age exceeds 40 years old.

Selection bias?

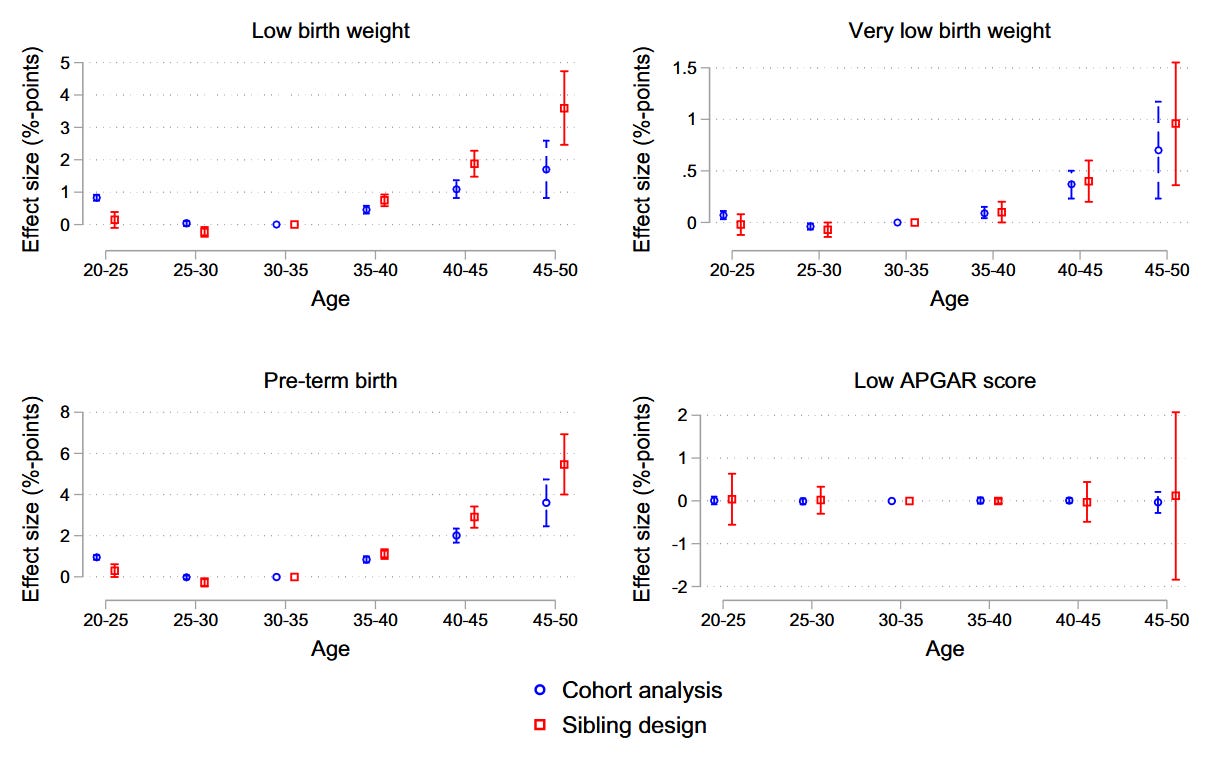

Maternal age is also a known risk factor for infant low birth weight or pre-term birth. In cross-sectional analyses, one generally observes a “U-shaped” association between maternal age and gestational age or birth weight. That is, increased risk of low birth weight in older mothers and in younger mothers.

However, when we deal with human subjects, we should always ask whether selection bias might affect our results. It is possible that older mothers differ from younger mothers in relevant characteristics other than age itself.

One advantage of the previously cited Danish study on chromosomal abnormalities is that, in Denmark, a large fraction of fetuses are cytogenetically examined, even in case of a late miscarriage or stillbirth. In many other studies, only live-born children are examined (Frederiksen et al., 2024). Thus, this study should at least be less contaminated by selection/survivorship bias.

But other research designs have also been used to help address selection bias, such as the sibling design. In this research design, they compare siblings born to the same parents, where parental age at childbearing (obviously) differs. By comparing siblings with the same parents, any parental factors that are stable from one birth to the next are automatically controlled for.

At least three sibling studies have been used to further interrogate the association between maternal age and the risk of low birth weight (Hvide et al., 2021; Sujan et al., 2016; Lawlor et al., 2011). Their findings suggest that the two sides of the U-shaped curve have different causes.

The relationship between advanced maternal age and low birth weight persists within families, consistent with a causal interpretation. In fact, if anything, these studies suggest that the cross-sectional associations slightly underestimate the effect of advanced age. This might be because those who have children later otherwise tend to be healthier for other reasons, partly masking the deleterious aging effect.

On the other hand, the studies suggest that the relationship between young maternal age and low birth weight is due to confounding. This would suggest that — contrary to advanced age — young maternal age itself is not an issue. Rather, women who become mothers at young ages are different in relevant respects other than just age.

Hvide et al. (2021) also use the sibling design to ascertain the effect of parental aging on other birth defects. The relationship persists within families, consistent with the hypothesis that age causally affects risk of birth defects.

Men’s or women’s age?

So far I have focused exclusively on maternal age. But partner ages are strongly correlated. If the mother is old, the father typically also is.

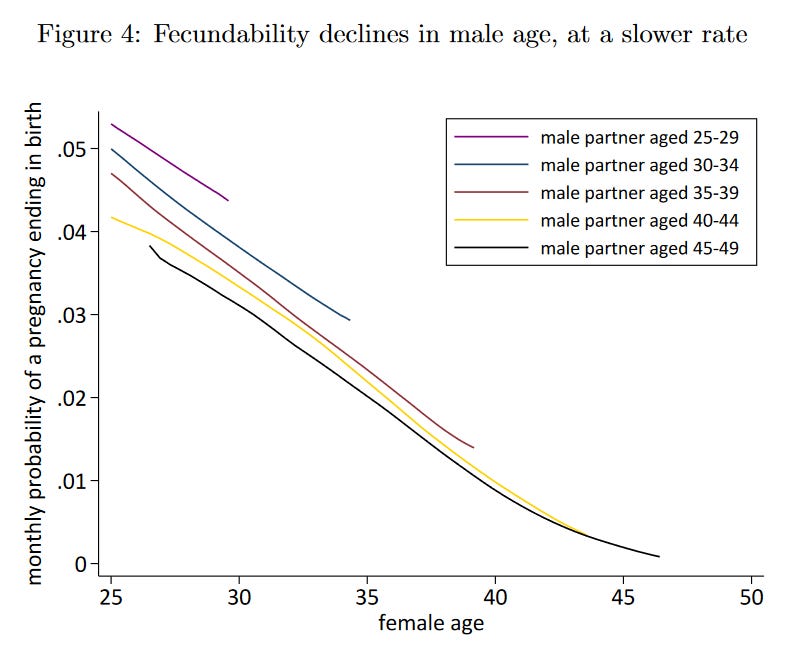

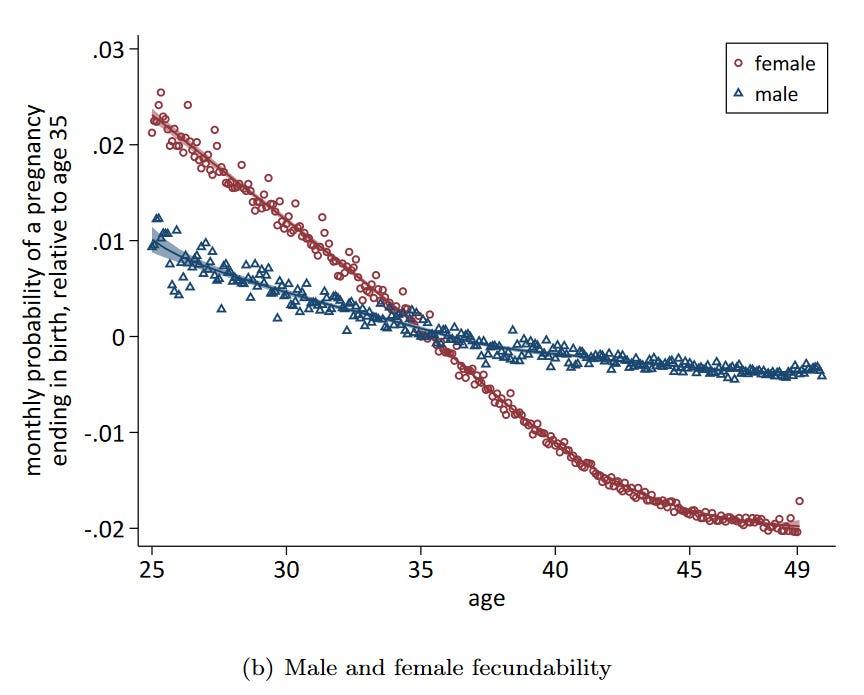

It’s therefore worth investigating to what extent this is driven by the father’s age rather than the mother’s. Geruso et al. (2023) show that fecundity also declines with paternal age, albeit at a slower rate.

The fact that maternal age has greater influence is more clearly illustrated in the following graph. The decline in fecundity is much more steep for women.

Hvide et al. (2021) also show that the risks of congenital malformations and infant mortality are greater when the mother is older than the father, supporting the notion that maternal age has a greater influence.

Bad wombs or bad eggs?

What is it about the female reproductive system that is so affected by age?

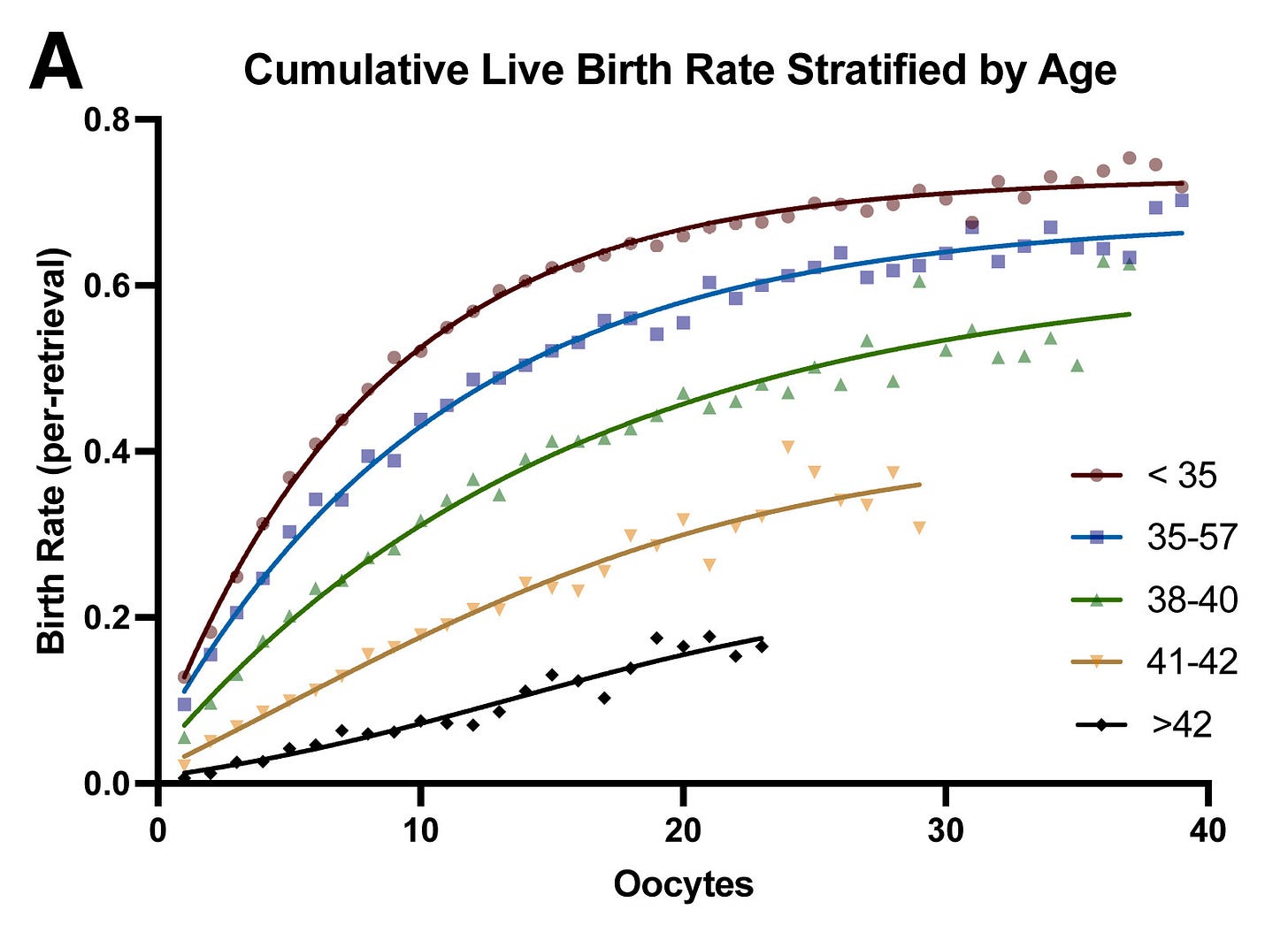

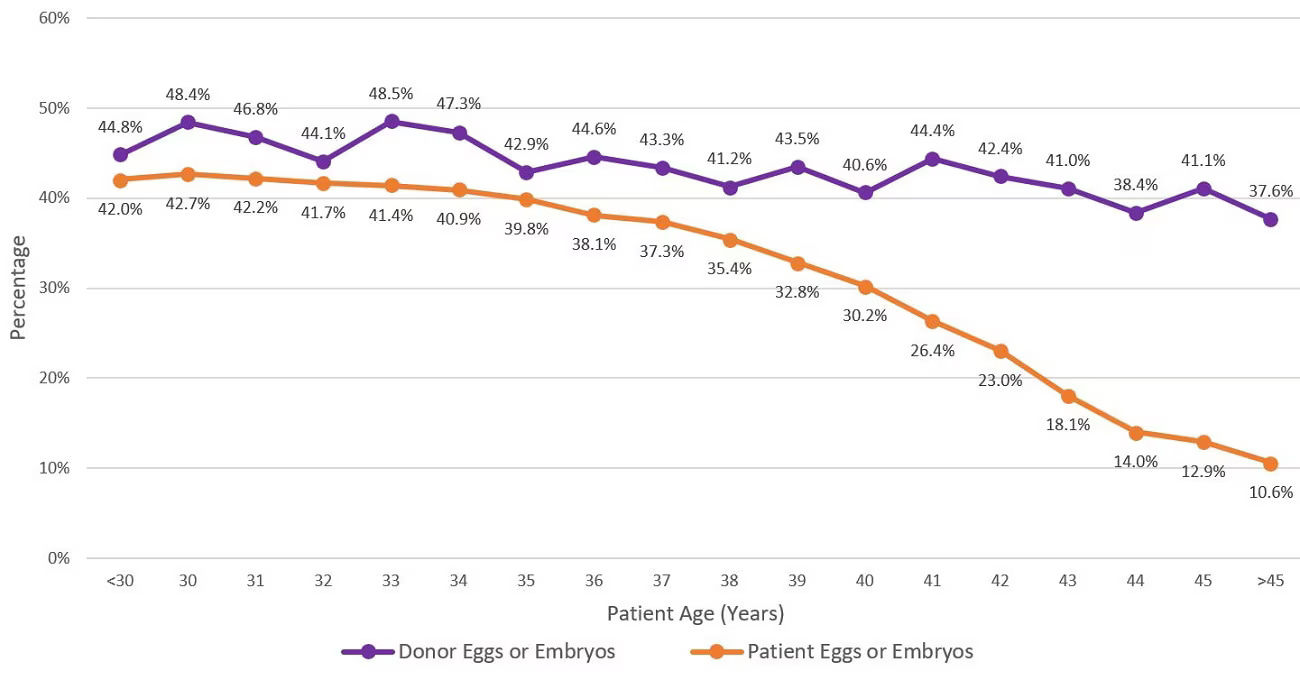

If we compare people who have received donor eggs and those who use their own eggs, the answer becomes immediately clear. As shown by CDC (2020) and Johnson & Tough (2012), when women use donor eggs, their own age has very little effect. It’s not the age of the mother that matters per se — it’s the age of the eggs.

In fact, there are two major determinants of success in assisted reproductive technology: (1) age of retrieved eggs, and (2) number of eggs retrieved. As long as many eggs are retrieved, and they are not retrieved too late, the success rate is high — as illustrated below.

These findings suggest that women who freeze eggs can easily become pregnant later in life, as long as they freeze their eggs when they are sufficiently young.

Unfortunately, this latter point has not been sufficiently acknowledged, and poor results of fertility treatments can mostly be chalked up to women starting the process too late. If egg freezing is here to stay, it has to be communicated to women that they should do it when they are still young.

Conclusion

We all know that infertility becomes more likely with advanced age. But it is widely believed that fecundity only marginally declines in a woman’s twenties, and then rapidly declines in her mid-thirties.

Yet a new study has shown that this appears to be a misconception. The shape of this age-fecundity curve is a statistical artifact, the result of various statistical issues related to how fecundity has been improperly estimated. In fact, the decline in fecundity that women experience in their twenties is as real as the decline in their thirties.

It is not only women’s age that matters. Though the effect is smaller, paternal age also affects the likelihood of a successful pregnancy. And, in regards to the importance of maternal age, we can be more specific about what really matters: mainly the age of the eggs. Evidence shows that, if a woman uses donor eggs, her own age plays little role in determining the success rate.

As the practice of egg freezing becomes more common, it is important that women have an understanding of the relevant facts. There is a high chance of success, provided that she doesn’t wait too long to do it.

For any woman who considers a future with children, and isn’t attempting to become pregnant in the short term, it might be a good idea to undergo the process sooner rather than later.