Where parents make a difference

Where is the shared environment effect larger than zero?

In the debates surrounding nature versus nurture, there are many who (incorrectly) deny the importance of nature. Then, based on their reading of the behavior genetics research, some make the completely opposite assertion. For example, in his book Blueprint, the behavior geneticist Robert Plomin has a section called “Parents matter, but they don’t make a difference.” On Twitter/X I see similar claims with some regularity. Is this true? No, I will argue, the behavior genetics literature does not support this position either.

Common interpretation errors

In discussions related to this issue, there are a few common interpretation errors that I think are worth addressing right off the bat:

Dismissal of “small” variance components. When the shared effect is estimated to be, say, 5% or 10%, these effects are often dismissed as negligible. But when we discuss social outcomes — which are influenced by many factors, each of small relative effect — such effects are by no means trivial or unimportant, even if they are smaller than the effect of genetics.1

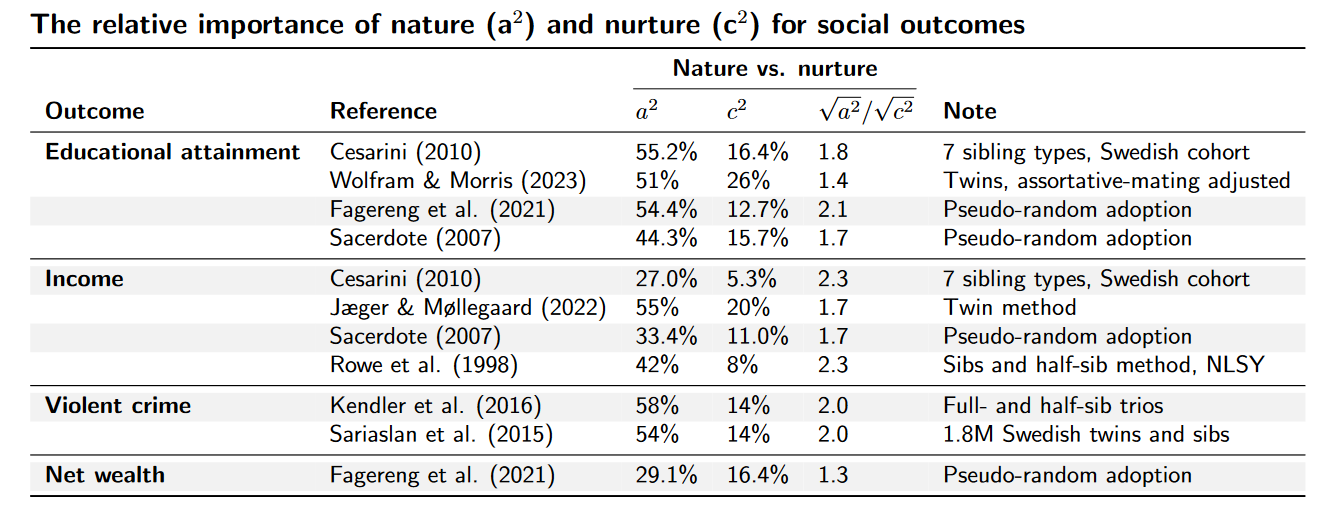

Properly comparing effects. When we wish to compare the relative effects of additive genetics (a²) and the shared environment (c²), we need to square root them (see, e.g., Del Guidice, 2021). For example, if heritability is 40% and shared environment 10%, then the effect of genes is twice as large as that of the shared environment effect, not four times [√(0.40)/√(0.10) = 2]. A factor 2 difference is substantial, but not so large it makes sense to call one effect big and the other negligible.

Lack of power, and statistical insignificance does not imply zero difference. The assertion of “0% shared environment” is typically just a lack of statistical power, where the component is not significantly different from 0. But that does not mean the best point estimate is 0%. For example, the idea that identical twins reared apart (MZA) are as similar as identical twins reared together (MZT) is very likely just the consequence of MZA samples being too small to reliably tease out small but real differences in correlations (though large enough to confirm the importance of genetics).

What does the evidence say?

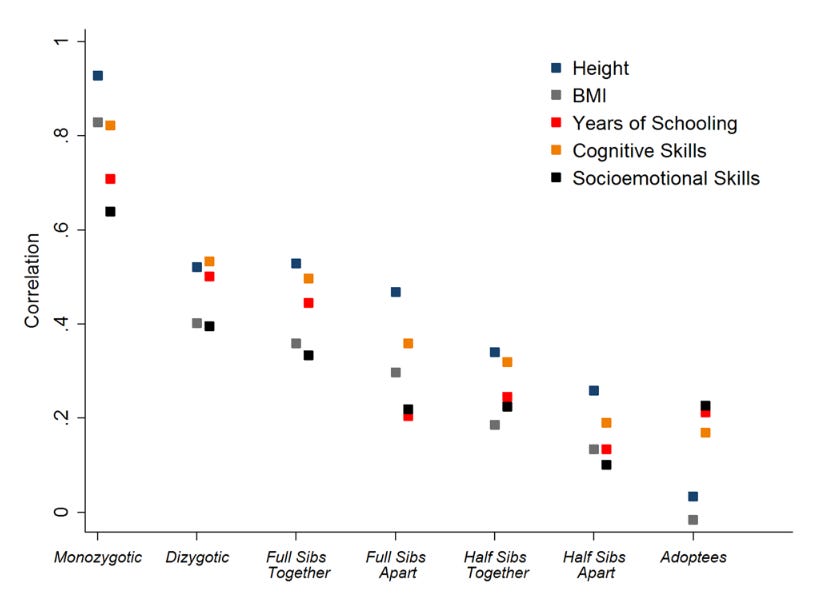

To get started, consider the following figure from Cesarini & Visscher (2017). It is based on the analysis by Cesarini (2010) with a massive Swedish cohort, showing how similar various sibling types are with respect to five different traits: height, BMI, years of schooling, cognitive skills, and socioemotional skills. These sibling types are, for example, monozygotic (“identical”) twins reared together, full siblings reared apart, and adoptees reared together.

Note that for Years of Schooling, Socioemotional skills and Cognitive Skills, the siblings reared together are always a little more similar than the equivalent siblings reared apart — an indication of a shared environment effect. Full siblings reared together are more similar in years of schooling than full siblings reared apart, etc. Unrelated adoptees reared together also show a nontrivial amount of similarity for the three traits (as much or more than half siblings reared apart).

Sibling similarity is, of course, also strongly related to genetic similarity, indicative of a large genetic effect. But as I said, I am not arguing that there there is no genetic effect, or even that the shared environment effect rivals the genetic effect, only that the shared environment effect is nonzero.

Educational attainment

Educational attainment is one of the clearest examples of a nonzero shared environmental component. The analysis by Cesarini (2010) mentioned above confirmed that years of education had a nontrivial shared environment effect, with an estimate of 16.4% (Table III.IV).

Classical twin studies confirm that educational attainment has a nonzero component. This is true even if assortative mating is accounted for — a phenomenon which will bias the estimates towards overestimating the shared environmental effect in twin studies (and underestimating the genetic effect). Wolfram & Morris (2023) find that, when assortative mating is adjusted for, the shared environment effect for educational attainment is estimated at 26%. However, according to their estimates, 16 percentage points were twin-specific, and a 10% shared environment component remained that was not specific to twins. Kemper et al. (2021) find an adjusted figure of 25% (Supplementary Table 13).

Adoption studies confirm that educational attainment is correlated not just with biological parents, but also adoptive parents (Björklund et al., 2007; Björklund et al., 2006). Sacerdote (2007) analyzes a Korean-American adoptive sample, and what is particularly interesting from a methodological perspective is that assignment to adoptive families was effectively random — adoptive families couldn’t choose which Korean child they would adopt. This removes worries of potential biases introduced by selective placement. Sacerdote found that all educational outcomes measured showed nonzero shared environmental effect (14% to 34%, depending on outcome, Table V). For highest grade completed, the heritability was 44.3% and shared environment 15.7%. Fagereng et al. (2021) looked at a Korean-Norwegian adoptive sample, again with effectively random assignment, and found a shared environment effect of 12.7% for the educational outcome.

Holmlund et al. (2011) review multiple methods of estimating the causal effect of parents’ education on offspring educational attainment. They conclude that there clearly is a causal effect beyond genetic inheritance, though they agree the causal effect is much smaller than the overall parent-offspring correlation (consistent with, e.g., genetic effects being important). Another study also found that, if a parent dies while the child is young, the child becomes less similar to that parent in terms of educational attainment (Gould et al., 2020).

Shared environment not only affects educational attainment, but which field you study. Altmejd (2023) provides compelling causal evidence of parental major choice on offspring major choice by exploiting admission thresholds — if a parent manages to get into a field of choice, the child is much more likely to pursue that field than if the parent fell just short of the admission cutoff. This also affected occupational choice.

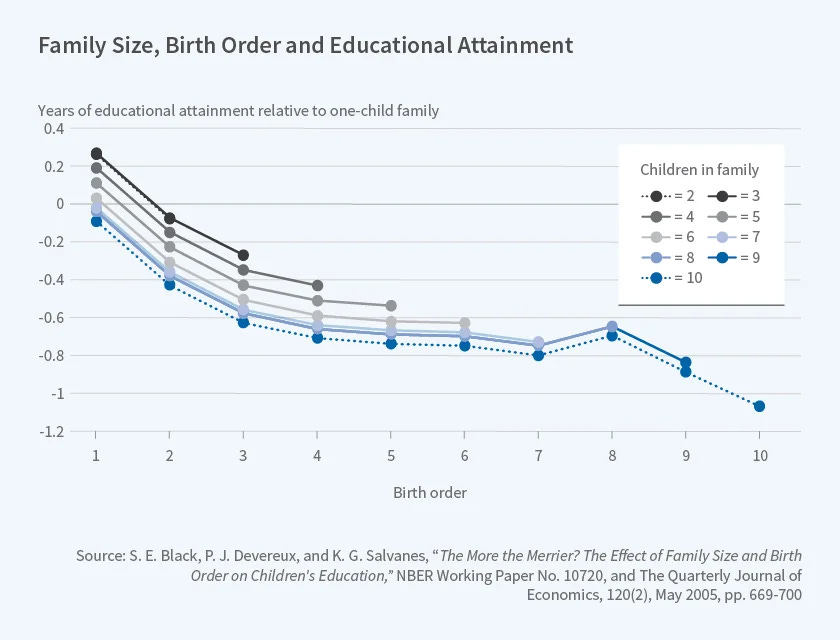

Another indication that nurture matters in the context of educational attainment is a highly replicated birth order effect, with earlier-born siblings nontrivially outperforming later-borns (Black et al., 2005; French et al., 2023). Isungset et al. (2022) and Barclay (2015) provide some compelling evidence that the birth order effect arises out of the postnatal environment.2

What about the shared environment is it that matters? This is more difficult to answer. An adoptive study by Anderson et al. (2020) finds that, at least in the American context, family income and parental expectations may be important (though parental expectations may be endogenous). However, it’s probably fair to say that we need more evidence to elucidate this question (see also Freese & Jao, 2015).

Income, earnings and wealth

Studies where variance decomposition estimates are made for income are less common than for educational attainment, mostly because the latter is simpler to measure. There is also less consistency in the results (in part, because income can be measured in different ways, over different periods of time, etc). However, all the evidence considered together, the most reasonable conclusion is that there is also a shared environmental effect on income.

Hyytinen et al. (2019) reviewed multiple twin studies with income measures from USA, Sweden, Australia and Norway. The average shared environment estimates were, respectively, 9% (USA), 13% (Australia), and 5% (Sweden). That itself averages to 9%. In a more recent analysis, Jæger & Møllegaard (2022) consider a large Danish twin sample and look at the origins of cultural tastes. However, they also look at some social outcomes, including income, for which they found a heritability estimate of 55% and a shared environment effect of 20%. Using the NLSY, an American sample with siblings and half-siblings, Rowe et al. (1998) estimate that income has a heritability of 42% and the shared environment of 8%.

In a huge Swedish sample using many sibling types (not just twins), Cesarini (2010) estimated heritability of income to be 27.0% and shared environment component to be 5.3% (Table III.IV). This result is arguably more trustworthy than the previous studies because (as it uses many sibling types) it is less affected by specific twin effects and assumptions arising from solely using twins. Taking these estimates for granted, it would imply that the genetic effect is 2.3 times as large as the shared environment effect [√(0.270)/√(0.053)].

Adoption studies are consistent with income having a nonzero shared environment effect. Using Swedish administrative data for all legal adoptions, Björklund et al. (2006) find that child income is associated with the incomes of both biological and adoptive parents. Sacerdote (2007), who analyzed a Korean adoptive sample with pseudo-random assignment, also looked at income. He found that family income had an estimated heritability of 33.4% and shared environment 11.0%, and log-income a heritability of 32.4% and shared environment, 13.9%.

Somewhat relatedly, Fagereng et al. (2021) analyze a Korean-Norwegian adoptive sample (again with pseudo-random assignment) and find evidence of a clear intergenerational transmission of wealth, even for adoptive children. They find that the transmission strength is about half as big for adoptees (without genetic similarity) as in ordinary families where both genetic and environmental similarity is present.

Like educational attainment, birth order also affects earnings (Black et al., 2005, Table IX; Daysal et al., 2023).

Crime

There are many small behavior genetics studies of crime or other measures of antisocial behavior. But the largest and most convincing studies to date are based on Swedish population registers.

Frisell et al. (2011) analyzed 12.5M Swedish individuals and how violent crime runs in families. Their results are most consistent with an effect of both nature and nurture on violent crime propensity (though the effect of nature seems larger). For example, there was still a significant relationship between parents’ criminal behavior and adoptive offspring’s criminal behavior.

Sariaslan et al. (2015), based on 1.8 million Swedish siblings and twins estimated that the heritability of violent crime to be 54% and the shared environment component 14%. Similarly, Kendler et al. (2016), based on a large sample of Swedish full- and half-siblings, estimate the heritability of male criminal behavior to be 58% and shared environment 14%. Frisell et al. (2012) show that the shared environment component remains larger than zero when assortative mating is accounted for. In a later paper, Kendler et al. (2019) looked at how estimates of the shared environment component depended on which familial relatives were used to construct the estimates. For criminal behavior, estimates of the shared environment component was between 16% and 30%, significantly greater than zero in all methods.

Adoption studies appear to confirm a shared environmental effect. Kendler et al. (2014) looked at about 18,000 Swedish adoptees along with their adoptive and biological relatives. Consistent with shared environmental effects, adoptive children showed some similarity in criminal behavior with their adoptive siblings and adoptive parents. Parental divorce, parental death and parental illness of the adoptive parent were also all associated with increased criminal behavior, i.e., not confounded by genetics.

Birth order also appears to affect crime (Breining et al., 2020).

Final thoughts

There are many people who overestimate the effect parents have on children’s outcomes. If you observe an association between parent and offspring and naively interpret that as simply the effect of parenting (“the nurture assumption”), you’re making a mistake. In all likelihood, genetic transmission accounts for a large fraction of that association.

The Second Law of Behavior Genetics states: the effect of being raised in the same family is smaller than the effect of genes (Turkheimer, 2000). I don’t make the slightest claim to overturn this law. The evidence I've reviewed, summarized in the table below, is very much consistent with it. But a² > c² and c² = 0 are very different statements. A rule of thumb seems to be that genetic effects tend to be roughly twice as impactful as that of nurture in determining differences in social outcomes.

For at least educational attainment, crime and income, the assertion that c² > 0 is supported by multiple lines of evidence. Variance decomposition estimates, using not only twins but multiple other relative types, confirm this. It is also supported by adoption studies, even with pseudo-random assignment. Further, a variety of other clever designs support it (e.g., the regression discontinuity design showing that parental major affects offspring major), and so does evidence from birth order effects. We should evaluate claims by the preponderance of evidence, and for social outcomes, the most reasonable, evidence-based conclusion is that c² > 0.3

In an Intelligence Squared debate, Stuart Ritchie says “Parenting does matter, but it doesn’t matter as much as you think.” I wholeheartedly agree. Parents matter and they make a difference, even if the difference they make is far from as decisive as old-school sociologists thought (and some incorrectly maintain to this day). Yes, the adage that both nature and nurture matter is boring. It is also true.

For example, Plomin writes: “As a parent, you can make a difference to your child’s beliefs, but even here shared environmental influence accounts for only 20 per cent of the variance.” But 20% is a substantial effect!

Daysal et al. (2023) hypothesize that birth order effects are due, at least in part, to siblings bringing home germs and spreading disease to the younger siblings. Disease in critical early stages of development may stunt long-term development in several ways. If true, that is still a way in which parents can affect their children, though admittedly quite indirect.

A possible objection is that the shared environment component is due to sibling effects. This distinction is interesting, but is not particularly relevant for my central claim — after all, it is the parents who provide siblings or not. So even if the entire parental effect was mediated by siblings affecting each other (which I think is unlikely), it would not disprove that parents make a difference. Additionally, several of the studies I’ve cited show that correlations between adoptive parents and adoptive offspring.

Parenting matters a lot in areas that are not being measured by psyshometricians. Religion, table manners, personal hygiene, etc. are traits that are transmitted mainly through nurture. Yes, the first law of behavior genetics says that very trait is heritable, including religiosity. But parents are the ones that teach their kids to brush their teeth after every meal. Not all cultures teach this.

And ultimately these behaviors that are taught at home are what defines a culture.

Parenting can make a BIG difference in choices made. My son was probably more criminally inclined than I. I had figured out at a teenager that it if your objective was to live a free life, it was easier to be a legitimate business than a criminal business (even if nobody is complaining about your activities, there is always the IRS asking questions about your income). So I would watch, monitor, and call him on activities, and ask him how he intended to not get caught. Eventually he realized that he did not have the detailed planning skills to cover his traces and that he was better off being legitimate. I pointed out to him that being able to think like an attacker was critical to defensive actors, who are both legitimate and can be paid very well. I also pointed out that he would have to undergo routine background checks and would have to limit his activities and associates accordingly. He did his MIS in data security and works successfully in the field.