The Assimilation Myth

Across the world, ethnic socioeconomic disparities are here to stay

See also:

Introduction

In a previous piece, I argued that commonly held notions about assimilation in America—“the melting pot”—are filled with exaggeration and fiction. Rather than quickly vanishing, ethnic disparities were often remarkably persistent, and their consequences can still be observed to this day.

This is by no means unique to America. Using international data, this piece evaluates the strength of assimilation with respect to several socially important domains. I focus mainly on three dimensions of socioeconomic performance: human capital, economic performance and crime. Lastly, I also briefly consider some other dimensions of cultural inheritance.

What exactly is meant by “assimilation”? According to the Encyclopedia Britannica: “The process of assimilating involves taking on the traits of the dominant culture to such a degree that the assimilating group becomes socially indistinguishable from other members of the society.”

The fundamental consequence of assimilation is that group disparities disappear, as one group converges to the other in the aggregate. This, as I’ll argue, is a process that is typically slow and/or incomplete.

Human capital

Human capital is arguably the central component of the modern knowledge economy. We can measure human capital with various proxies such as educational attainment and educational performance, or performance on standardized cognitive or aptitude tests.

Immigrants and natives often differ substantially in human capital. This in itself isn’t terribly surprising. Immigrants typically grow up with a different language and attending highly different schools.

The question then is, do immigrants generally rapidly assimilate in human capital? The answer is a clear no. This observation is well-captured by the title of a 2011 article analyzing PISA data: “Why do the results of immigrant students depend so much on their country of origin and so little on their country of destination?”

But it’s not just first-generation immigrants. It’s also their descendants.

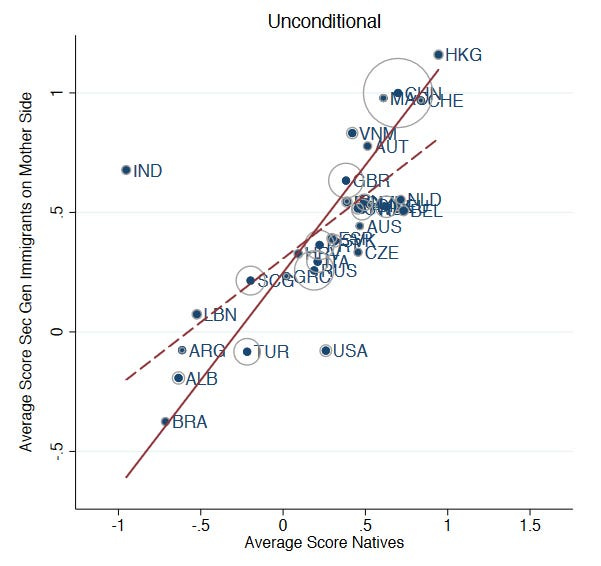

As shown below, there is a very strong relationship between parents’ native country-of-origin scores and second-generation immigrant scores (De Philippis & Rossi, 2020). That is, second-generation immigrants tend to score much more similar to people in their parents’ country-of-origin, and not like the country they were actually born and raised in. In short, human capital persists substantially across borders.

In another systematic evaluation of immigrant competences using international PISA, TIMMS and PIRLS data, Rindermann & Thompson (2016) found that the native-immigrant gap, on average, is reduced only by the equivalent of ~1 IQ point from first and second generation (though there was significant heterogeneity by origin and receiving country).

The findings of De Philippis & Rossi (2020) go even further. They show that, even among students who attend the same school and controlling for socioeconomic factors, students whose parents come from high-scoring countries tend to perform better.1

Where large deviations from the trend are observed — like India — it is indicative of strong immigration selection, not of assimilation. That is, those who migrated were unrepresentative of their country fellows prior to migration.2

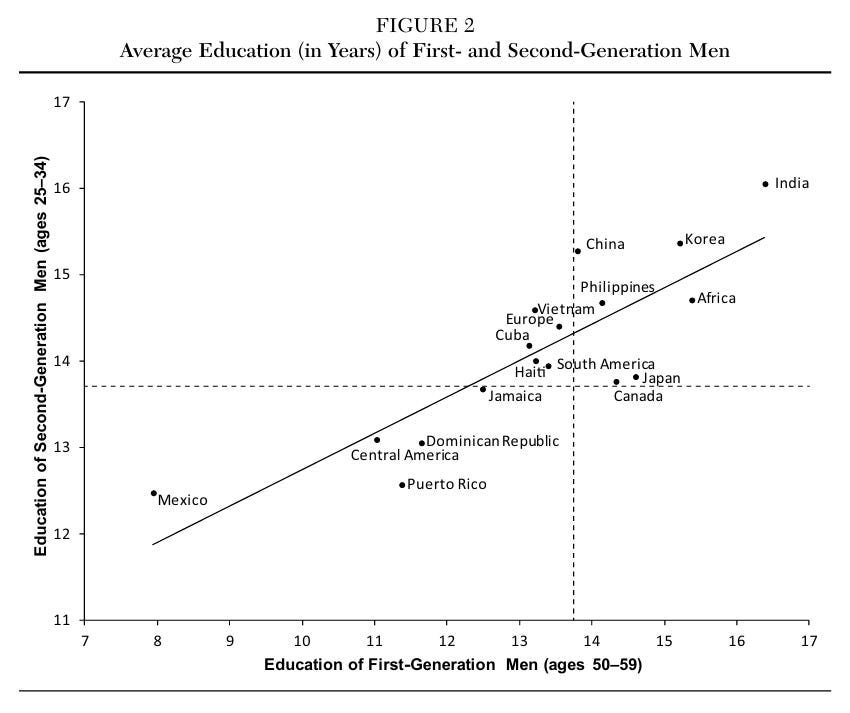

The fact that immigrant performance is strongly related to immigrant selectivity or, more broadly, to pre-arrival characteristics is well-documented (Duncan & Trejo, 2015; Werfhorst & Heath, 2018; Ichou, 2014; Hanson & Liu, 2023). Note, for instance, the high educational level of Indian first-generation immigrants illustrated below (which is far higher than the average person in India). These pre-arrival educational disparities also predict immigrants’ earnings.

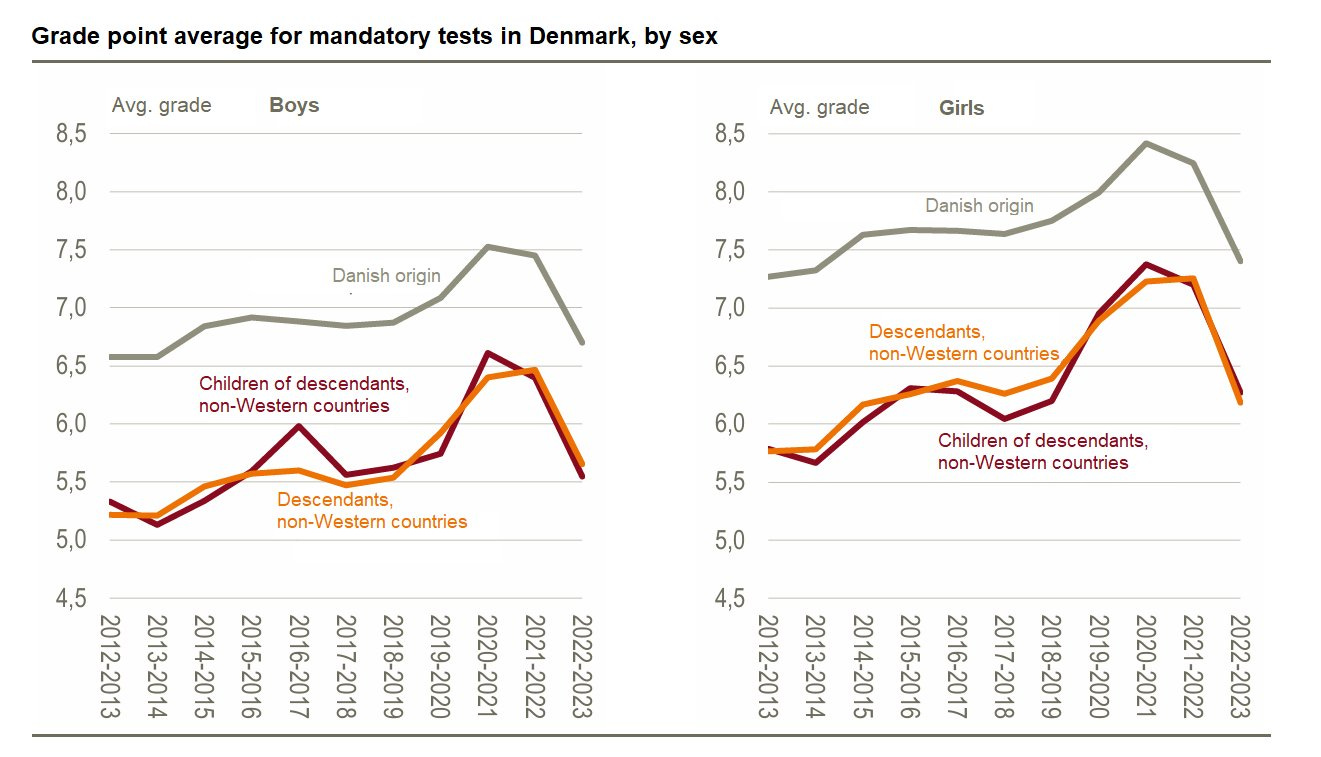

In Denmark, non-Western immigrants attain significantly lower grades than native Danes (and Western immigrants for that matter). There is a significant improvement from first- to second generation (especially in Danish language tests), but substantial differences remain.3

Interestingly, Statistics Denmark have also published results on the children of descendants — that is, third-generation immigrants. The results suggest there is little to no further convergence from second to third generation.4

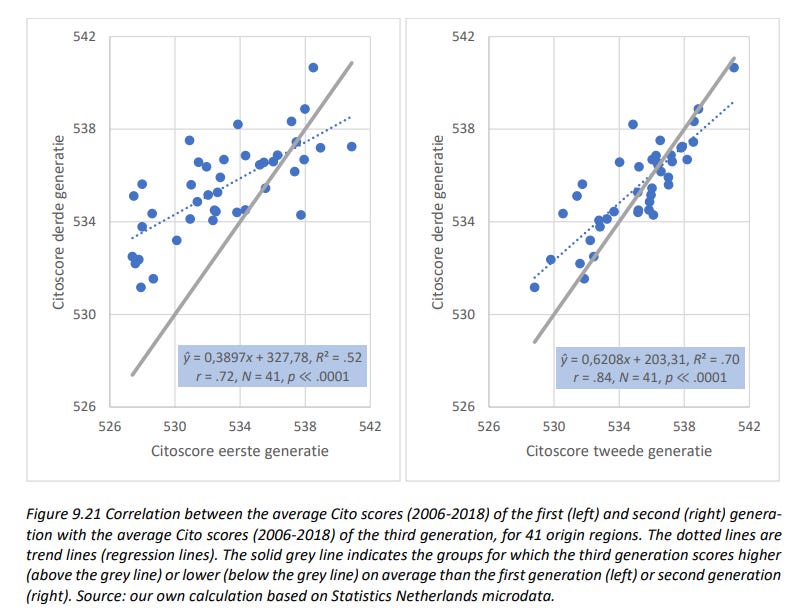

This is consistent with findings by Dutch researchers (van de Beek et al., 2023). They found that there are large differences in human capital by immigrant regional origin, and there is strong persistence at least until third generation.5

Similarly, based on more than four generations of historical data, Telles & Ortiz (2008) found no support for the assimilation theory with respect to educational attainment among Mexican immigrants in the United States.

Human capital also doesn’t just persist with willing migration. Toews & Vézina (2025) show that the enemies of the people who were forcibly sent to Gulag labor camps nevertheless had persistent human capital across generations. The loss of human capital, such as the dismissal of scientists in Germany under World War 2, also resulted in long-run costs (Waldinger, 2016).

In a classic paper, Borjas (1992) argues that persistent disparities in human capital (or SES) must be understood in terms of what he calls “ethnic capital.” The idea is that intergenerational mobility depends not only on the parental input (nature and nurture), but “also on the average skills of the ethnic group in the parent’s generation.” He suggests that other ethnic group members represent externalities that influence (for better or for worse) the environment in which the child accumulates human capital.

Regardless if Borjas is right about the underlying mechanism, it’s an important observation that individuals from different groups regress to different means. This makes the between-group convergence slower than what is observed for individual differences within-group.

In the following sections, I evaluate the evidence regarding assimilation with respect to economic performance, crime and culture.

Economic

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Patterns in Humanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.