Notable People in Science, Europe 1000-1850

Based on a publicly available dataset, I track the European geographical distribution of notable scientists, philosophers, and other intellectuals from 1000 AD until the Industrial Revolution. Here I give a brief overview of the analysis and then I list the particularly noteworthy individuals within each period.

Introduction

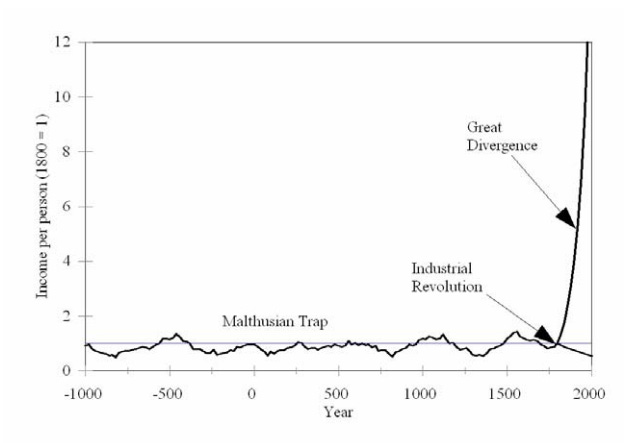

The Industrial Revolution, occurring in the decades around 1800, is often considered the most important event in human economic history; revolutionizing manufacturing processes and providing an escape from the ‘Malthusian trap’ which otherwise dominated history. Understanding the antecedents of this event is therefore of great interest to many, myself included.

For this reason, I created an animation tracking the distribution of notable people in science, philosophy, and discovery in the period 1000-1850.

Watch the full animation here.

Download a long list of >5,000 notable people here. Chronologically sorted and especially notable people are marked with asterisks (*).

The animation is based on the database released by Laouenan et al. (2022), consisting of notable people from recorded history using various editions of Wikipedia. This rich dataset proved to be a great resource to analyze the topic at hand, including data about birth year, birthplace, occupations and indicators of notability.

Without getting into too heavy detail, a very brief overview of my analysis is as follows. Based on several Wikipedia indicators (e.g., article length, number of languages the person is documented in) I created an overall proxy of “notability” for each individual using principal component analysis. I further restricted the analysis to people living in the relevant time period, born in Europe, and in the most relevant occupation categories provided by the authors of the database.

I then wanted to visualize the geographical distribution of notable individuals across time. Each notable individual “lights up” at their birth place, with the size and intensity of the light being determined by the person’s notability score and age (a curve that starts at zero at age zero, grows into middle age, and slowly fades after). Influence is additive at any location, meaning that any location’s intensity is a function of each individual’s intensity as well as the sheer number of notable individuals born in that vicinity.

To give context to the main topic, which is the 1000—1850 period, I have also devoted a section to pre-1000 and a section to post-1850. I will now list some of the most notable people related to science in each period.

Before 1000 AD

If one is to discuss the history of science in Europe, one must mention the Greeks. Before the year 0, they create a rich intellectual tradition that is enormously influential for centuries (and even millennia) to come. Said to be ‘the first philosopher’, the ‘father of science’, and the ‘first true mathematician’, the Greek Thales of Miletus (b. ~624 BC) is particularly noteworthy. Thales is the first known person to whom a mathematical proof has been attributed.1 The most famous philosophers of this period are Socrates (b. ~470 BC), Plato (b. ~428 BC) and Aristotle (b. 384 BC).

The Greeks are also the first to establish a rigorous discipline of mathematics. Thales, perhaps the first true mathematician, was mentioned above. Further, Euclid (fl. ~300 BC) is famous for his Elements, a major mathematical treatise. This is the oldest extant work that engages in a large-scale series of deductive proofs, based on a few select axioms. Before the Ancient Greeks, mathematics was based mainly on rules of thumb rather than rigorous deductive proofs. Arguably the greatest ancient mathematician is Archimedes (b. ~287 BC), whose mathematical accomplishments are astounding for his time, and who also is notable as a physicist and engineer.

In the health sciences, Hippocrates (b. ~460 BC) is said to be the ‘father of medicine’ and, born centuries later, Galen (b. 129 AD) is also one of the most influential people in medicine.

The works of Cicero (b. 106 BC) are also of note, as more than a thousand years later, his letters help initiate the Renaissance.

The old Greco-Roman civilizations last a long time, and there are of course many more notable people. Others worth mentioning are Anaximander (b. ~610 BC), Pythagoras (b. ~570 BC), Parmenides (b. ~515 BC), Herodotus (b. ~484 BC), Democritus (b. ~460 BC), Thucydides (b. ~460 BC), Epicurus (b. 341 BC), Eratosthenes (b. ~276 BC), Vitruvius (b. 80 BC), Hero of Alexandria (b. ~10 AD), Pliny the Elder (b. ~23 AD), Ptolemy (b. ~100 AD), Origen (b. ~185 AD), Plotinus (b. ~204 AD), Diophantus (b. ~200 AD), Augustine of Hippo (b. 354 AD), and Boethius (b. 524 AD).

The fall of the Roman empire after 400 AD brings not only the loss of political territory, but the Greco-Roman dominance in the realms of science and philosophy is also no longer. Boethius has been called the “last of the Roman philosophers and the first of the scholastic theologians,” and it will take some time before Europe sees the likes of Aristotle or Archimedes again.

From roughly 800-1050 AD, Scandinavia is in the era of the vikings. While they are skilled shipbuilders and sailors, and have a writing system and poetry, these Norsemen have no intellectual tradition that compares with the Greco-Romans. They do, however, make an impressive discovery. Starting from Scandinavia, vikings sail far across the oceans. First they discover Iceland; later Greenland, which is settled by Erik the Red (b. ~950 AD); and eventually they manage to reach continental North America. They are the first Europeans to discover this continent, and this feat will not be redone for another half millennium. According to the sagas, Leif Erikson (b. ~970 AD) is the one who discovers continental North America and establishes the first Norse settlement there.

In the remainder of Europe — that which is not Mediterranean nor Scandinavian — we see the early intellectual seeds growing in places such as the British Isles, France and Germany. While it is fair to say that the scholarship here is in many ways underdeveloped when measured against the extraordinary Greco-Romans, it is a mistake to think of it as intellectually and culturally barren with little but religious superstition. The lives and works of numerous people are a testament to an impressive emerging intellectual tradition. Examples of notable people are Alcuin of York (b. ~735 AD), Dungal of Bobbio (fl. 811–828 AD), Ratramnus (b. ~800AD), Rudolf of Fulda (b. ~800 AD), Walafrid Strabo (b. ~808 AD), Remigius of Auxerre (b. ~841 AD), John the Exarch (b. ~850 AD), Æthelweard (b. ~947 AD), Dudo of Saint-Quentin (b. ~965 AD), and Berengar of Tours (b. ~998 AD). Arguably, the most notable is the Irish philosopher John Scotus Eriugena (b. ~800 AD), who has been called the “the most astonishing person of the ninth century.”2 But the greatest of science has yet to come in Europe, and the next sections will list some of the numerous notable individuals who bring that to fruition.

Years 1000-1120

In 1100 AD much of Spain has been ruled by Muslims for centuries, and notable people such as Ibn Hazm (b. 994), Avempace (b. ~1085), Ibn Zuhr (b. 1094), and Ibn Tufail (b. 1105) reflect this. Non-Islamic Europe near this period also has its fair share of notable people, including the Byzantine Greek Michael Psellos (b. ~1018), German chronicler Adam of Bremen (b. ~1050), the French philosopher Roscellinus (b. ~1050), English philosopher and translator Adelard of Bath (b. ~1075), French philosopher Peter Abelard (b. ~1079), the English historian William of Malmesbury (b. ~1095), and the Italian scholastic theologian Peter Lombard (b. ~1096).

In the middle ages much, if not most, scholarship occurs in a religious context. The origin of many medieval universities, the first of which are yet to be established, can also be traced back to Catholic cathedral or monastic schools. Medieval scholars are also more sophisticated than they are often given credit for. For example, contrary to what's often suggested, scholars of this time know that the Earth is not flat. This is revealed in the writings of multiple medieval scholars. For example the historian introduced above, Adam of Bremen, mentions this fact about the Earth in passing as if it's widely understood among learned people.3

Years 1120-1230

By 1230, several universities have appeared in Europe, some of which exist to this day. Examples are the universities of Bologna, Paris (closed intermittently due to the French Revolution), Oxford, Salamanca, and Cambridge.

Some notable individuals around this period include the Sephardic philosophers Maimonides (b. ~1138) and Nachmanides (b. ~1194), Cambro-Norman historian Gerald of Wales (b. ~1146), Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus (b. ~1150), the influential English Robert Grosseteste (b. ~1168), German friar Albertus Magnus (b. ~1200), English Roger Bacon (b. ~1219), and the explorers Benjamin of Tudela (b. 1130) and William of Rubruck (b. ~1220). Grosseteste and Bacon are noteworthy for their emphasis on empiricism and are considered by many particularly important for the development of modern science in Europe.

Al-Andalus (Muslim-ruled Iberia) continues to have some notable names like Averroes (b. 1126), Ibn al-Baytar (b. 1197) and Ibn al-Nafis (b. 1213). The Italian Gerard of Cremona (b. ~1114) translates many of the Arabic scientific works into Latin. Islamic intellectuals were greatly influenced by the Ancient Greeks, and the rediscovery of much Ancient Greek scholarship in Europe comes from translations from Arabic (which itself had been translated into Arabic).

North Italy is becoming increasingly influential. Particularly of note is Pisa’s Fibonacci (b. ~1170), one of the most important medieval mathematicians. Among many other contributions, he helps popularize the Hindu-Arabic numeral system in Europe. The astronomer and teacher at the University of Paris, Johannes de Sacrobosco (b. ~1195), also writes a short introduction to the Hindu-Arabic numeral system, and this book becomes the most widely read book on the topic in the following several centuries.

Years 1230-1360

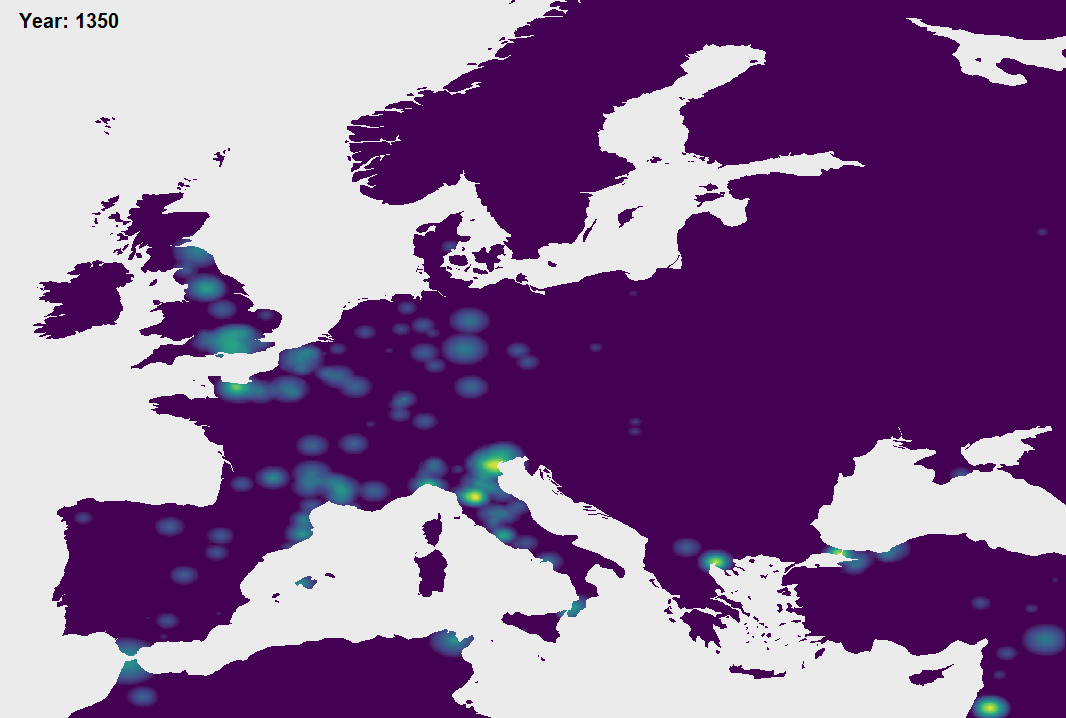

Notability is spread around United Kingdom, France, Germany and, particularly, North Italy.

Notable people include the the French Vincent of Beauvais (b. ~1184), who worked on an early encyclopedia from 1235 to 1264, a major compendium of contemporary knowledge. Further, the philosopher from Mallorca Ramon Llull (b. ~1232), the German Meister Eckhart (b. ~1260), the Scottish philosopher Duns Scotus (b. ~1265), the English philosopher William of Ockham (b. ~1285), the French Nicole Oresme (b. ~1325), the English John Wycliffe (b. ~1328) are all noteworthy.

Italy continues its great influence with notable individuals such as Bonaventure (b. 1221), Thomas Aquinas (b. 1225), and the famous explorer Marco Polo (b. 1254) from Venice.

Bonaventure, Aquinas, Scotus and Ockham together form the four most important Christian philosopher-theologians of the High Middle Ages. These theologians not only write about religion, but also have considerable influence on secular thought and make important intellectual contributions to the development of science.

Years 1360-1450

Europe is slowly entering the Renaissance phase, marking its transition from the Middle Ages to modernity. Many regions in Europe are intellectually active but Italy is clearly still on top, particularly the cities of Florence, Padua and Venice.

Humanism is a dominant theme of Renaissance philosophy with Leonardo Bruni (b. ~1370), Poggio Bracciolini (b. 1380), Nicholas of Cusa (b. 1401), Lorenzo Valla (b. ~1407), and Marsilio Ficino (b. 1433), and many others.

Filippo Brunelleschi (b. 1377) is a greatly influential architect and engineer, considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture. Other notable people include Prince Henry the Navigator (b. 1394), the German mathematician Regiomontanus (b. 1436), and perhaps most importantly, Johannes Gutenberg (b. 1394), the inventor of a mechanical printing press, a major milestone accelerating the transmission of intellectual work.

Years 1450-1560

The entire Central and Western Europe light up. By 1500, more than 50 universities have been established throughout the continent in what are presently the countries of Italy, France, United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Czech Republic, Poland, Austria, Hungary, Germany, Albania, Croatia, Belgium, Switzerland, Sweden, and Denmark. The ‘university’ is arguably an exclusively European institution, although other kinds of centers of learning have existed outside Europe (e.g. in China, India and the Islamic world).

Raphael’s The School of Athens, Renaissance painting from 1511, depicts many figures we’ve covered so far

At this point even the most notable people are becoming too numerous to all be mentioned. The single most famous person in this period is the Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci (b. 1452). Other noteworthy figures from Italy include Luca Pacioli (b. ~1447) and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (b. 1463).

The biggest mathematicians of this period are Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia (b. ~1499), Gerolamo Cardano (b. 1501) and François Viète (b. 1540). They progress mathematics in a number of ways. Historically, mathematical equations and calculations were described verbally, but in this period numerous steps are taken towards a more concise and efficient symbolic algebra.

Astronomy, and empirical science more broadly, make great progress with Nicolaus Copernicus (b. 1473) and Tycho Brahe (b. 1546), who both make pioneering contributions to the scientific revolution. Other names here include Giordano Bruno (b. 1548) and John Napier (b. 1550).

Important contributions to anatomy and the ‘medical revolution’ are done by Paracelsus (b. ~1493), Ambroise Paré (b. ~1510), Andreas Vesalius (b. 1514), the ‘founder of modern anatomy’, and Hieronymus Fabricius (b. 1533).

Influential thinkers of other kinds include Erasmus (b. 1466), considered one of the greatest scholars of the Northern Renaissance, as well as the political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli (b. 1469). The religious domain has noteworthy names in Thomas More (b. 1478), Martin Luther (b. 1483) and John Calvin (b. 1509) of ‘Calvinism’.

The age of exploration is also upon Europe, and alongside Italy’s continued great influence, Spain and Portugal are important in this domain. Italy has John Cabot (b. ~1450), Amerigo Vespucci (b. 1451) and the famous Christopher Columbus (b. 1451). Portugal has Bartolomeu Dias (b. ~1450), Vasco da Gama (b. ~1469), and Pedro Álvares Cabral (b. ~1467), and Ferdinand Magellan (b. 1480). Spain has Juan Ponce de León (b. 1474), Vasco Núñez de Balboa (b. ~1475), Francisco Pizarro (b. 1478) , and Hernán Cortés (b. 1485). Relatedly, geography and cartography also makes important progress with notable individuals Garardus Mercator (b. 1512) and Abraham Ortelius (b. 1527).

By 1560, the major coasts of America have largely been explored, and the Spanish conquistadors have encountered the Incas and conquered the Aztec Empire. Portuguese explorers have passed the southern tip of Africa, reaching India, and established new important spice trade routes.

Years 1560-1630

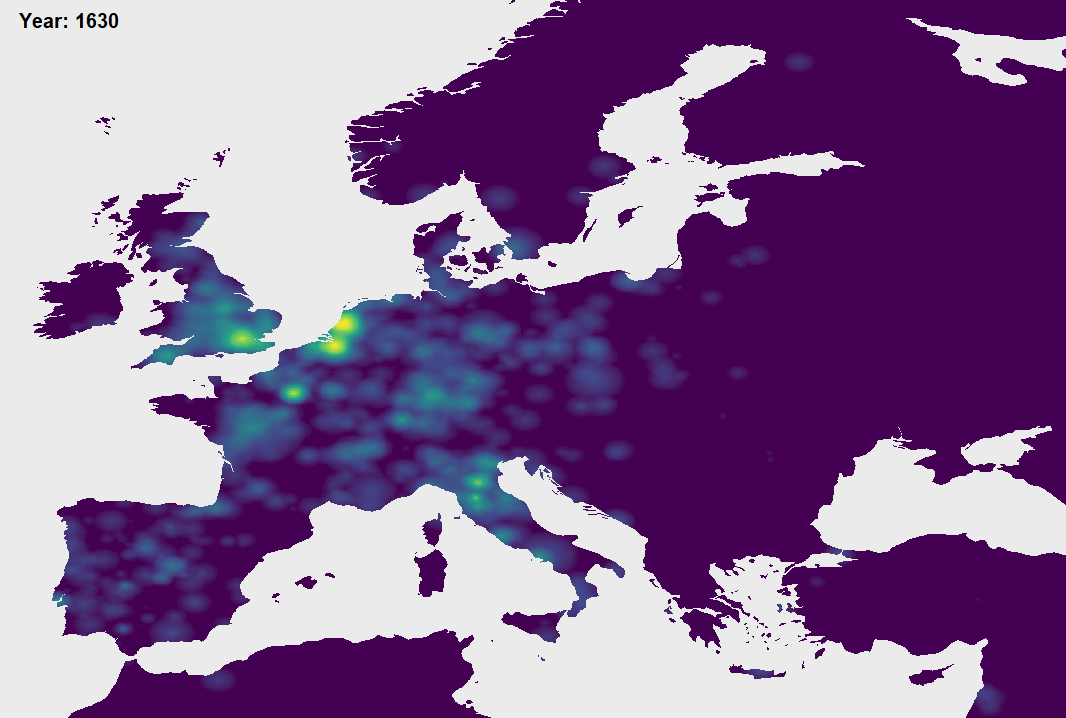

Italy is still highly active but no longer dominant. Notability has moved more to the northwest in Europe and four cities in particular light up: London, Paris, Amsterdam, and Antwerp.

This period has notable philosophers such as Francis Bacon (b. 1561), the ‘father of empiricism,’ Hugo Grotius (b. 1583), and Thomas Hobbes (b. 1588). The most influential philosopher and mathematician is probably René Descartes (b. 1596).

In his later years, the astronomer and mathematician Christopher Clavius (b. 1538) is one of the most respected astronomers at this time. The most famous and arguably most influential individuals in this discipline, however, are Galileo Galilei (b. 1564) and Johannes Kepler (b. 1571).

By 1630, the understanding of astronomy has greatly improved. The increasingly more accurate empirical astronomical measurements, which especially Tycho Brahe was an early pioneer of, make it clear that early models of the solar system are inadequate. Copernicus had forwarded the model of the solar system where plants orbited the Sun in circular paths. Through analyzing the astronomical observations of Tycho, Kepler develops his three laws of planetary motion and establishes that orbits are elliptical rather than circular. The more accurate understanding of orbital paths, alongside Galileo’s discoveries of celestial bodies that do not orbit the Earth, give credence to the correct heliocentric view.

Other noteworthy figures in this period include the polymath Athanasius Kircher (b. 1602), the seafarer Abel Tasman (b. 1603), the physicist and mathematician Evangelista Torricelli (b. 1608), and the French mathematician Pierre de Fermat (b. 1607). The anatomist and physiologist William Harvey (b. 1578) makes the most detailed description of the blood circulatory system to date.

Years 1630-1740

Spain has seen a substantial downward trend in notable people from 1500 to 1700. Notability continues to be clustered in Paris and London, and also across the Netherlands and Germany.

Important names in the physical sciences and engineering include Robert Boyle (b. 1627), Christiaan Huygens (b. 1629), the military engineer Sébastien de Vauban (b. 1633), and Robert Hooke (b. 1635). Astronomy has important names such as Ole Rømer (b. 1644), the first to measure the speed of light, and Edmond Halley (b. 1656).

Mathematics and physics undergo tremendous progress. Isaac Newton (b. 1643) and Gottfried von Leibniz (b. 1646) independently create what we now call ‘calculus’, essential for mathematically describing many physical phenomena. Newton also establishes classical mechanics with his laws of motion, bringing about a unification of the current understanding of gravity with other observable phenomena in the universe. This also sets heliocentrism on a firm theoretical foundation. These names are already impressive enough, but it doesn’t stop there. The philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal (b. 1623) is highly notable and later comes the birth of Leonhard Euler (b. 1707), one of history’s most important mathematicians. Other important mathematicians and physicists include the brothers Jacob (b. 1655) and Johann Bernoulli (b. 1667), Johann’s son Daniel Bernoulli (b. 1700), and the French Émilie du Châtelet (b. 1706) and Jean d’Alembert (b. 1717).

Important names in the life sciences include ‘the father of microbiology’ Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (b. 1632), Maria Sibylla Merian (b. 1647), the Swedish ‘father of modern taxonomy’ Carl Linnaeus (b. 1707), and Count Buffon (b. 1707).

Notable philosophers and thinkers in other domains include John Locke (b. 1632), Baruch Spinoza (b. 1632), David Hume (b. 1711), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (b. 1712), Adam Smith (b. 1723) and Immanuel Kant (b. 1724).

Scientists are increasingly engaging in systematization. Individual pieces of knowledge are not only gathered, there is also an attempt to understand them together according to overarching theories or principles. Newton establishing how gravity on earth and planetary orbits together can be understood by one and the same theory is an excellent example of this. Another great example is Carl Linnaeus formalizing binomial nomenclature and embarking upon the greatest attempt so far of classifying life forms. A compelling theory to understand how all these different life forms have emerged is still required and the central figure here, Darwin, is born circa thirty years after the death of Linnaeus.

Years 1740-1850

The Industrial Revolution is undergoing at full force. The three most important European countries appear to be the United Kingdom, France and Germany, however certainly with plenty of activity outside those countries too.

Possibly the most important component of industrialization is the transition to mechanical manufacturing processes and taking control of electricity. The steam engine by James Watt (b. 1736) is a great example of this. A particularly notable engineer is Isambard Brunel (b. 1806) who makes important contributions to technology for bridges, ships, tunnels and railways.

Pioneering work towards understanding and controlling electricity is done by people such as Alessandro Volta (b. 1745), André-Marie Ampère (b. 1775), Hans Christian Ørsted (b. 1777), Georg Ohm (b. 1789), and Michael Faraday (b. 1791). This eventually develops into an understanding of the connection between electricity and magnetism — electromagnetism — the second great unification in physics (the first being Newton unifying gravity and the laws of motion). This unification reaches its conclusion when it becomes mathematically described by the equations of James Maxwell (b. 1831).

Charles Babbage (b. 1791) invents the first mechanical computer. The true potential of mechanical computers and computerized algorithms will of course only be realized more than a century later (with many notable and important people along the way); which is itself a different kind of revolution beyond the industrial one.

Chemistry also progresses greatly in this period. Important names here include Joseph Priestley (b. 1733), Antoine Lavoisier (b. 1743), and John Dalton (b. 1766), the latter whom introduces atomic theory. Additionally, Amedeo Avogadro (b. 1776), Humphry Davy (b. 1778), and Jöns Jacob Berzelius (b. 1779) are notable. Arguably, ‘modern chemistry’ is established in this period.

In mathematics, both pure and applied (e.g. in physics), several important names come to mind: Joseph-Louis Lagrange (b. 1736), Pierre-Simon Laplace (b. 1749), Joseph Fourier (b. 1768), Augustin-Louis Cauchy (b. 1789), Augustin-Jean Fresnel (b. 1789), Niels Abel (b. 1802), Évariste Galois (b. 1811), George Boole (b. 1815), William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (b. 1824) and Bernhard Riemann (b. 1826). The biggest of them all, however, is Carl Friedrich Gauss (b. 1777). It is sometimes said that, if you want to guess who is responsible for a discovery in mathematics, chances are you’ll be correct if you guess either Gauss or Euler.

In the life sciences, we also have a number of important names. The most obvious being Charles Darwin (b. 1809), who revolutionizes biology with his theory of natural (and sexual) selection. But many others are worth mentioning. Edward Jenner (b. 1749) creates the world’s first vaccine (against smallpox). Alfred Wallace (b. 1823) independently conceives of many similar ideas as Darwin. Gregor Mendel (b. 1822) makes important discoveries on how heredity works. Other notable people include Georges Cuvier (b. 1769), Justus von Liebig (b. 1803), Louis Pasteur (b. 1822), Francis Galton (b. 1822), Thomas Henry Huxley (b. 1825). Pasteur, for example, makes major contributions to the understanding of causes and preventions of diseases. He discovers important principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization.

Despite centuries of global exploration, much of the world remains unexplored by Europeans into the 1800s, particularly land not near any coasts. A number of explorers are worth mentioning, for example James Cook (b. 1728), famous for his journeys to New Zealand and Australia, and Mungo Park (b. 1771), the first European person to record travels into the deep interior regions of West Africa.

Numerous influential philosophers exist in this period. These include Georg Hegel (b. 1770), Arthur Schopenhauer (b. 1788), the liberal philosophers Alexis de Tocqueville (b. 1805) and John Stuart Mill (b. 1806), and the existentialist Søren Kierkegaard (b. 1813).

Beyond the Industrial Revolution (1850-1950)

Rapid progress in science and technology continues beyond the industrial revolution. First, multiple engineers making important technological contributions are worth mentioning. Alexander Graham Bell (b. 1847) patents the first practical telephone. Nikola Tesla (b. 1856) does important work related to electricity. Guglielmo Marconi (b. 1874) creates a radio wave-based wireless telegraph system and is considered the inventor of the radio.

The building blocks of matter are subject to ever greater investigation, leading to a more accurate understanding of matter at the smallest scale. J. J. Thomson (b. 1856) discovers the electron, the first subatomic particle discovered. Wilhelm Röntgen (b. 1845), Pierre Curie (b. 1859), Marie Curie (b. 1867), and Otto Hahn (b. 1879) conduct pioneering research into the radioactivity, and Ernest Rutherford (b. 1871) has become known as the ‘father of nuclear physics.’

The most famous scientist is undoubtedly Albert Einstein (b. 1879), who makes pioneering contributions to quantum mechanics, alongside important figures such as Planck, Bohr, Schrödinger, Heisenberg, Born, Dirac, among others (these influential individuals captured in the famous picture above of the gathering at the fifth Solvay conference in 1927). Einstein, however, is most famous for developing the theory of relativity, ultimately superseding the more than 200 years old framework of classical mechanics of Newton. The understanding of the properties of nature at the scale of (sub)atoms ultimately also leads to one of the most potent discoveries: the atomic (nuclear) bomb. Enrico Fermi (b. 1901) is also worth mentioning here as the first to create a nuclear reactor.

A few mathematicians are of particular noteworthiness in this period. These are the logician Gottlob Frege (b. 1848), Henri Poincaré (b. 1854) and David Hilbert (b. 1862). Poincaré and Hilbert have both been considered the last mathematicians who excelled in all major fields of the discipline4. Influential for both mathematical and philosophical reasons, there is also Bertrand Russell (b. 1872). Theorems established by Emmy Noether (b. 1882) are of great importance in mathematical physics, and John von Neumann (b. 1903) makes major contributions to many fields, e.g., in mathematics, physics, computing, and statistics.

There is also growing interest into understanding human and animal behavior, which develops into the social sciences such as psychology, sociology and economics. Francis Galton (mentioned in the previous section) is considered by some the founder of behavioral genetics. Ivan Pavlov (b. 1849) discovers classical conditioning through his experiments on dogs. Sigmund Freud (b. 1856) is undoubtedly one of the most famous psychologists (or, in some circles, the most infamous). Carl Jung (b. 1875), like Freud, is also famous for his work on psychoanalysis, although Jung develops it in a different direction. Alfred Binet (b. 1857) establishes the first practical IQ test, and Jean Piaget (b. 1896) is well known for his research on children’s mental development. Émile Durkheim (b. 1858) establishes the academic discipline of sociology. In economics, John Maynard Keynes (b. 1883) and Friedrich Hayek (b. 1899) are particularly influential.

Statistics as a discipline matures. Galton makes some of the earliest pioneering contributions to statistics. Karl Pearson (b. 1857), who also works with Galton, is often credited with establishing the discipline of mathematical statistics. Ronald Fisher (b. 1890) also makes numerous major contributions to statistics and, taking steps further, he combines statistics with genetics which helps establish the fields of quantitative genetics and population genetics; one of the greatest in biology since Darwin. Speaking of biology, in 1953, the (correct) double helix structure of DNA is proposed and published in a paper by Watson and Crick.

Important discoveries in biology also help combat disease. Robert Koch (b. 1843) discovers the causative agents of various deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax. Alexander Fleming (b. 1881) discovers penicillin, an effective antibiotic.

Several philosophers are also notable. Examples are Friedrich Nietzsche (b. 1844), Martin Heidegger (b. 1889) and Ludwig Wittgenstein (b. 1889). In the context of people of science, the philosopher of science Karl Popper (b. 1902) is perhaps of extra note. Popper introduces the concept of falsification, which, in the popular mind, sometimes seems almost synonymous with the scientific method (despite its relatively recent introduction in the history of science).

As we move closer to modern technology, a few names are notable. Wernher von Braun (b. 1912) is a pioneer of rocket and space technology and in 1969 the first human crew lands on the moon. Alan Turing (b. 1912) is influential in the development of theoretical computer science as well as cryptography. Computer technology progresses throughout the century in a number of ways. In 1947 the transistor is invented by John Bardeen (b. 1908), Walter Brattain (b. 1902) and William Shockley (b. 1910). In 1957 the first personal computer controlled by one person is invented by IBM. Also in 1957, the optical amplifier is invented; foundational to powering the internet. This marks the transition into a new period, sometimes referred to as The Information Age.

Thales of Miletus is described as the ‘first philosopher’ by many, most notably by Aristotle. In Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy, Russell writes: “There is, however, ample reason to feel respect for Thales, though perhaps rather as a man of science than as a philosopher in the modern sense of the word.” For being possibly the first to engage in a true deductive mathematical proof, Boyer & Merzbach write in A History of Mathematics: “Thales has frequently been hailed as the first true mathematician—as the originator of the deductive organization of geometry.”

In A History of Western Philosophy, Bertrand Russell writes: “John the Scot…is the most astonishing person of the ninth century; he would have been less surprising if he had lived in the fifth or the fifteenth century. He was an Irishman, a Neoplatonist, an accomplished Greek scholar, a Pelagian, a pantheist…He set reason above faith, and cared nothing for the authority of ecclesiastics; yet his arbitrament was invoked to settle their controversies.”

Adam of Bremen reveals that he understands that the earth is round when, in describing solstice, he writes: “That island sees the sun upon the land for fourteen days continuously at the solstice in summer and, similarly, it lacks the sun for the same number of days in the winter. To the barbarians, who do not know that the difference in length of days is due to the accession and recession of the sun, this is astounding and mysterious. For on account of rotundity of the earth, the sun in its course necessarily brings day as it approaches a place, and leaves night as it recedes from it." Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum. Book 4 (p. 219, in translation by Francis J. Tschan).

Hello, I found this picture and I wanted to know if it was related to this study : https://i.4cdn.org/pol/1683909508386602.jpg

If it is, is there a way to get the full database?

Are differences in population density taken into account in any way? For example, if two cities had a population of 1 million and 1 thousand respectively, and each had 10 geniuses, would they both be equally "lit up," or would the latter be brighter since the proportion of geniuses is so much higher?