Genes and social stratification

How genes affect socioeconomic success, and its consequences for society's structure.

In this piece, I will first summarize some of the evidence demonstrating that genes matter for socioeconomic success. Then I will discuss some heritable traits that influence socioeconomic success. Lastly, the consequences for how genes are distributed throughout society will be discussed. This is a follow-up of my previous piece, in which I discuss the effect of nurture.

Content list:

Introduction

Genetic influence on socioeconomic outcomes

Characteristics of individual socioeconomic success

Cognitive ability

Personality

Mental health

Sorting and genetic stratification

Assortative mating

Vertical sorting and intergenerational persistence

Educational and occupational sorting

Regional sorting

International sorting

Conclusion

Introduction

The central topic of this piece is that socioeconomic success — e.g., education, occupation, and income— is, to some extent, influenced by genetic differences between individuals. Nurture matters, but nature matters and this has important consequences for the structure of society. As I will elaborate upon, observed differences in, say, intelligence between social classes, between schools, or between geographical regions, are all partly the result of the genetic composition of individuals inhabiting those environments.

This is not a new idea. The polymath Francis Galton’s systematic investigation of the inheritance of talent, and thus the inheritance of eminent status, is an early example that explores the topic of nature and nurture of occupational achievement (Galton, 1869). But arguably the clearest articulation of how heredity must influence not only things like height, eye color or facial morphology, but also things like social rank and earnings, comes from Richard Herrnstein’s infamous article 1971 article “I.Q.” He began his article with a syllogism, articulating point-by-point why the heritability of mental abilities ultimately leads to a (partial) heritability of social outcomes. Herrnstein based his conclusions on traditional behavioral genetics research designs — e.g., adoption and twin studies — but he did not have access to modern DNA evidence.

This piece revisits this topic, equipped with modern evidence.

Genetic influence on socioeconomic success

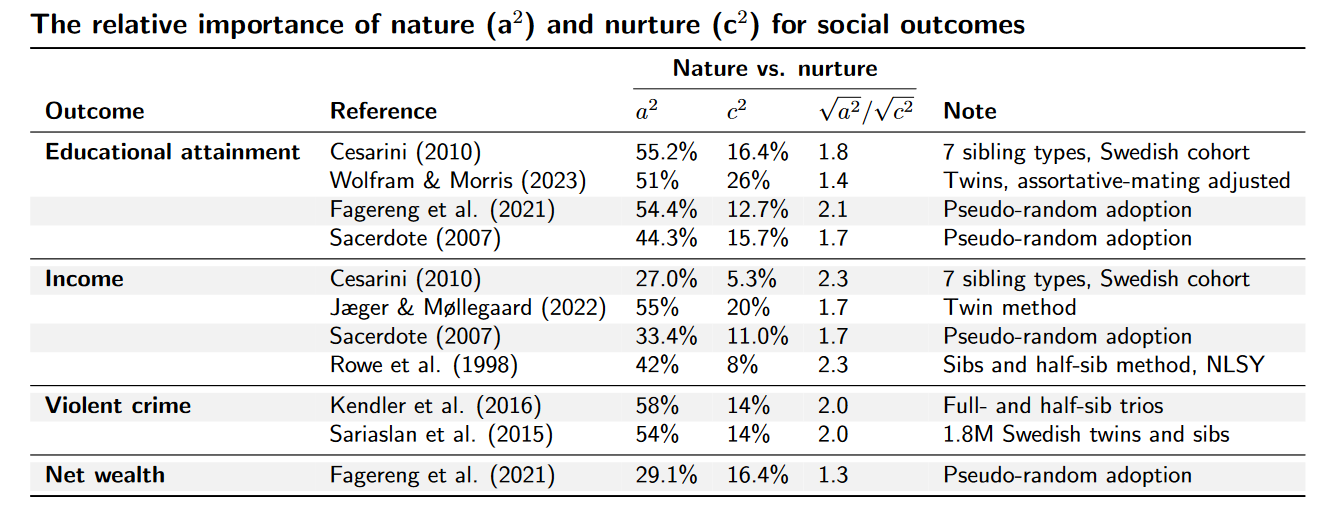

In a previous piece, I argued that parental differences have a nontrivial effect on social outcome differences. Together with other evidence, I included the following table illustrating that a variety of research designs confirm the shared environmental effect is above zero for some social outcomes. The cited studies also illustrate that the social outcomes show substantial heritability (a²), an effect roughly twice as large as that of the shared environment for these social outcomes.

Thus a large number of research designs — adoption (with pseudo-random assignment), twin studies, other pedigree studies — all confirm that socioeconomic success is heritable. As I have discussed these studies in the previous piece, I will not go into greater detail here.

The evidence that genes affect variation in socioeconomic success is even more conclusive however, as I will explain after some background. With genome-wide association studies (GWAS), researchers have begun to estimate how variation in small pieces of the genome are associated with various phenotypes, including physical, mental, behavioral and social phenotypes. Many phenotypes have been found to be extremely polygenic: affected by a huge number of genetic variants, each of which have a tiny effect individually, but the aggregate effect of all the tiny effects being substantial. In fact, adding up all the individual effects results in what is known as a polygenic score (PGS), a single value representing a genetic proxy for a specific trait in a single person. As genome-wide association studies improve, so increases the ability of the polygenic score to capture individual differences in genetic propensity for the trait in question. Most relevant for us are the genome-wide association studies for educational attainment (EA), the social outcome for which the largest samples have been acquired (Lee et al., 2018; Okbay et al., 2022). The EA polygenic score can today explain a reasonable chunk of out-of-sample variation in educational success, comparable to environmental correlates traditionally seen as highly influential (Raffington et al., 2020).

This leads us to the most conclusive evidence that genetic variation affects variation in socioeconomic success. Geneticists can exploit an important fact of nature: genetic differences between siblings are randomly assigned due to the process of meiosis (similarly, parent-offspring genetic differences are also random). In effect, it’s a naturally occurring randomized controlled trial. This means that if genetic differences between full siblings (or parent-offspring differences) are systematically associated with some phenotype, it represents a causal effect of genes on that phenotype (see, e.g., Biroli et al., 2022).1

Countless studies with large samples have been conducted to assess whether sibling differences in EA polygenic scores are associated with socioeconomic outcomes, and thus whether we can detect a causal effect of genes on those socioeconomic outcomes. The answer is a clear yes. This is true if the socioeconomic indicator is measured in terms of income or wealth accumulation (Barcellos et al., 2021; Belsky et al., 2018; Buser et al., 2023; Kweon et al., 2020), educational attainment or achievement (McGue et al., 2020; Ronda et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021), occupational attainment (Buser et al., 2023; Belsky et al., 2018), or neighborhood quality (Kweon et al., 2020). Socioeconomic success differences are thus unambiguously causally affected by genetic differences to at least a small extent.

Importantly, these studies only give us a lower bound on the causal effect of genes on social outcomes (Belsky et al., 2018). In short, because genetic predictors can only be improved. For one, the GWAS for educational attainment can still be improved, with larger samples and, importantly, better and more consistently measured phenotypes.2 Second, GWA studies currently only includes the effects of common genetic variation. The effects of rarer variants are not included, and rarer variants have larger absolute effects (Corte et al., 2023). Third, it only includes additive genetic effects.3 Fourth, given that genetic variance is reduced within families, correlations between genes and outcomes are artificially reduced due to range restriction; and this is further exacerbated by assortative mating (which is strong in the context of educational attainment).4 Fifth, polygenic scores for phenotypes other than EA would surely have a partially independent explanatory power of socioeconomic outcomes.

Some people occasionally express incredulity at all this: how could genes affect “environmental” outcomes like educational attainment? The answer is quite simple: because some characteristics that affect those outcomes — e.g., intelligence, personality, and mental health — themselves are heritable. If a trait X is heritable, and X affects an outcome Y, it is unsurprising that the causal chain would arise: genes →X→Y. So even the most environmentally-sounding things are usually affected by genes to some degree, as well as being affected by other factors.

Characteristics of individual socioeconomic success

What then are the characteristics that lead to individual differences in socioeconomic success?

Again genome-wide association studies (GWAS) can give us some clues. You can calculate the genetic correlation between different phenotypes. Roughly speaking, it’s a measure of how similar the genome associations are between two different traits analyzed in GWAS. Educational attainment has a strong genetic correlation with cognitive ability (~0.7). However, research shows that educational attainment is also downstream of other heritable characteristics, like personality and psychological well-being (Krapohl et al., 2014; Dermange et al., 2021).

Of individual psychological differences, we might hypothesize that three categories of (partially overlapping) traits are the primary determinants of socioeconomic success: (1) can-do traits (e.g., cognitive ability), (2) will-do traits (e.g., conscientiousness, industriousness, interests), and (3) mental health (e.g., low neuroticism and lack of mental disorders like schizophrenia).

In the following sections, I will consider cognitive ability, personality and mental health as three examples of heritable traits that influence socioeconomic success. After that, I will discuss the consequences this has on how people sort throughout society.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Patterns in Humanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.