Precolonial India was not rich

The historical poverty of the Indian masses, origins of the great divergence, and why East Asian growth miracle but not South Asian

Foreign travellers who visited India during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries present a picture of a small group in the ruling class living a life of great ostentation and luxury, in sharp contrast to the miserable condition of the masses — the peasants, the artisans and the domestic attendants. Indigenous sources do not disagree; they often dwell on the luxurious life of the upper classes, and occasionally refer to the privations of the ordinary people. (The Cambridge Economic History of India, p. 458)

Introduction

In popular discussions it is often suggested that India was historically a wealthy society. The standard line is that wealthy precolonial India accounted for a quarter of global GDP, a fraction that dramatically fell with ongoing British colonialism.

But the basic premise is false. Precolonial India was not rich. The living standards of commoners in 17th century India were not any better than medieval European peasants. The misconception is based on bad arithmetic, on conflating a large population with prosperity, on generalizing from the lives of elites, and on bad data.

The purpose of this piece is not to analyze the consequences of British colonialism, but to provide a more accurate account of the precolonial Indian economy. I’ll consider both the qualitative and quantitative evidence on the living standards in India. Then I will trace the origins of the developmental divergence between the West and India.

A misguided argument

“India used to be very rich. It once had more than 25% of the global GDP. After British colonialism, it fell to just 4% of world GDP.”

This is, in essence, the most common argument for the two-part claim that (a) India used to be very rich, and (b) that British colonialism caused the decline from this height. It is often accompanied by a graph like this (using long-run GDP estimates from Maddison, 2007).

There are three major problems with this argument.

The first is basic arithmetic. Because shares have to add up to 100%, a decline in global GDP share does not tell you that the size of the economy declined. A decline in share is just as consistent with other economies experiencing growth. The share of global GDP thus cannot be used as evidence for economic decline.

The second problem is data quality. In truth, Maddison’s estimates above were largely guesswork, at least for preindustrial non-Western countries. The economic historian Gregory Clark went further saying that, “All the numbers Maddison estimates for the years before 1820 are fictions.” Luckily, we now have access to better data than Maddison did.

The third problem is a conceptual misunderstanding about economics, namely the use of GDP rather than GDP per capita as a proxy for a “wealthy society.” In an agrarian society, GDP is largely food production and is mostly a proxy for population size rather than living standards.

The real measure of prosperity is quantified on a per-capita basis as that better reflects the living standards of actual people. Even if we accepted Maddison’s estimates for the sake of argument, we find that India was substantially poorer in per-capita terms than England in 1700 AD (Maddison, 2007; Table A.7).

In a similar vein, there’s a common misconception that natural resources like spices, diamonds or gold made India rich. On the contrary, a large, populous country containing natural resources tells you little about the living standards of its general population. Indian commoners were poor and couldn’t themselves afford many spices, diamonds, or luxurious textiles. Instead, modern wealth has emerged primarily through rises in productivity, not from natural resources.

The precolonial Indian economy

Living standards in 17th century India were not that unlike those in medieval Europe centuries earlier. It was an agrarian society, commoners lived primarily off the food they cultivated themselves, only a minority were acquainted with urban life, and the vast majority were illiterate. The average person was poor, and famine and epidemics were recurring threats.

There were, of course, wealthy kings, nobles and elites who lived in better conditions, but their rarity makes them less representative of the country’s living standards than the peasant. Slavery was also widespread in Mughal India, while serfdom predominated in medieval Europe.

A major difference was population size. India was substantially more populous than Europe prior to the Industrial Revolution, perhaps a quarter of the global population in 1500 AD, a fact often mistakenly interpreted as richness.

In a preindustrial world dominated by Malthusian constraints, a large and dense population was a liability—it reduced average living standards. Historically, a “large GDP” has been functionally equivalent to “many poor people.” Only after the Industrial Revolution could economic growth widely and persistently exceed population growth, resulting in skyrocketing living standards.

Qualitative evidence

British colonization of India happened well after the Age of Exploration, and many European travelers had already set foot in India. The British had not taken any significant control of India prior to around 1760. By 1820, India was de facto under British control, and their rule was formal between 1858 and 1947 under the British Raj.

European travelers in India encountered a society with a small ruling class living a life of great ostentation and luxury, sharply contrasted with the miserable poverty of the masses.

The Dutch merchant Francisco Pelsaert (c. 1595–1630), for instance, said of India:

The common people (live in) poverty so great and miserable that the life of the people can be depicted or accurately described only as the home of stark want and the dwelling place of bitter woe . . . their houses are built of mud with thatched roofs. Furniture there is little or none, except some earthenware pots to hold water and for cooking.

“Their bedclothes are scanty, merely a sheet, or perhaps two”, he continues, “this is sufficient in the hot weather, but the bitter cold nights are miserable indeed.”

Descriptions of this sort are repeated in numerous accounts. François Bernier (1620–1688) writes about Delhi:

for two or three who wear decent apparel, there may always be reckoned seven or eight poor, ragged and miserable beings.

Bernier compares this unfavorably with Paris in which “seven or eight out of ten individuals seen in the streets are tolerably well clad.”

William Harrison’s Description of England in 1577 provides another point of comparison. The book illustrates the rising prosperity in England for lower and upper classes alike. As he tells us, a growing number of Englishmen have chimneys instead of smoke holes; glazed windows instead of wooden lattices; regular beds instead of straw pallets; pewter plates instead of wooden platters, and tin and silver spoons instead of wooden ones. He also writes:

many farmers . . . garnish their cupboards with plate, their joined beds with tapestry and silk hangings, and their tables with carpets and fine napery

While modest in modern perspective, he is describing living standards that significantly surpass that of Indian commoners in 16th and 17th centuries. As we will see later, quantitative evidence supports this position.

Regarding food consumed in India, John Fryer (1650–1733) writes:

Boiled rice, nichany [the ragged millet], millet, and grass-roots, are the common food of the ordinary people.

Their single-room houses could be crowded, for Fryer notes that they “themselves, their family, and cattle, are all housed, and many times in no distinct partition.”

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605–1689) writes about the small wages of Indian diamond miners:

These poor people only earn 3 pagodas per annum, although they must be men who thoroughly understand their work. As their wages are so small they do not show any scruple, when searching the sand, in concealing a stone for themselves when they can, and being naked, save for a small cloth which covers their private parts, they adroitly contrive to swallow it.

Pelsaert concurs about the low wages in India, saying that “for the workman there are two scourges, the first of which is low wages” and “the second [scourge] is [the oppression of] the Governor, the nobles, the Diwan, the Kotwal, the Bakhshi, and other royal officers.”

Mughal sources rarely comment on the lives of commoners, instead focusing on elite perspectives, but when they do, they do not disagree with the European characterization.

Babur (1483–1530), the founder and emperor of the Mughal Empire, said “Peasants and people of low standing go about naked.” He also lists the deficiencies of India:

[T]here are no good horses, no good dogs, no grapes, musk-melons or first-rate fruits, no ice or cold water, no good bread or cooked food in the bāzārs, no Hot-baths, no Colleges, no candles, torches or candlesticks.

The Persian historian Firishta (ca. 1570–1620), in agreement with Palsaert about the oppressive ruling class in India, writes about Delhi sultan rule:

The duties levied on the necessaries of life realised with the utmost rigour, were too great for the power of industry to cope with: the country, in consequence, became involved in poverty and distress. The farmers fled to the woods, and maintained themselves by rapine; the lands were left uncultivated; famine desolated whole provinces, and the sufferings of the people obliterated from their minds every idea of subjection.

Abul Fazl (1551–1602), the great historian of Akbar’s reign, says that the common people of Bengal “for the most part go naked wearing only a cloth about the loins.”

Rice, millets and pulses formed the stable diet of the masses. But, as noted by Habib (1963, p. 91), “generally speaking, it was the lowest varieties, out of his produce, which the peasant was able to retain for his own family.” In the 16th century Ain-i-Akbari, Abul Fazl mentions that the ‘indigent’ resorted to eating ‘pea-like grain’, which used to cause sickness (Habib, 1963, p. 91). Meat was rarely eaten by Hindus due to taboos on beef and pork, but fish was consumed in some regions.

Based on these and other accounts (see, e.g., Chandra, 1982; Habib, 1963), and acknowledging that there could be substantial variety between regions, we may summarize the living standard of a typical Indian commoner:

Peasants were generally scantily clad, being naked save for a cloth around their waist, and usually went barefoot.

Daily food was very simple; a typical meal might be a portion of pulse mixed with rice and sometimes ghee. Fruits were also available according to region and season. Only the more prosperous villages could afford more than one meal a day. Many spices (e.g., cumin, cardamoms and pepper) were too expensive for commoners, and capsicums or chilies were unknown.

Peasants typically lived in single-room houses made of mud, wood or bamboo, with thatched roofs. The homes had minimal furniture and floors were traditionally coated with cow dung. Cities and houses were often crowded, and large families could reside in a single hut. In some areas, houses were so low that a person could not stand upright in them.

Famines and epidemics were two major scourges of village life. Lack or excess rain were frequent causes of failed crops. Big famines accompanied by epidemics could disrupt entire rural economies and led to mass migrations. Entire villages or towns could be temporary and huts were often not durable or long-lasting.

Quantitative data

The qualitative descriptions are consistent with quantitative data. Recent data solidifies the conclusion that India had substantially lower GDP per capita than West Europe before 1700 AD, as Maddison originally had surmised (Maddison, 2007, Table A.7). I will summarize this data after a little background on the agrarian economy.

Agrarian life

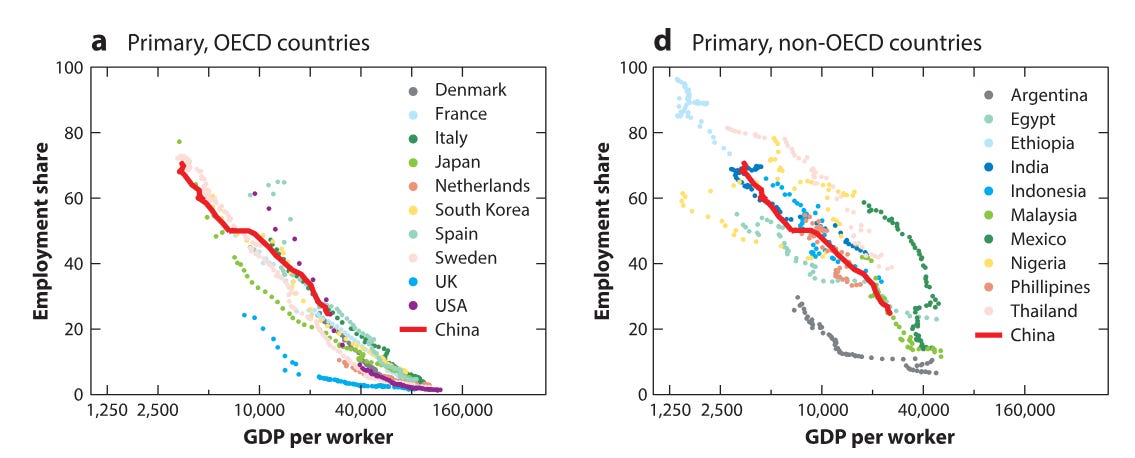

Major civilizations in history have all centered around agriculture. But as countries have gotten richer and more productive, fewer have needed to devote their efforts to agriculture in order to sustain the population. The share of labor in agriculture is therefore a strong (inverse) proxy for economic development.

Precolonial India was a prototypical agrarian society—the great majority lived in villages and worked in agriculture to feed themselves. As Gavin Hambly writes:

It is hardly necessary to observe that the majority of the inhabitants of the Indian sub-continent during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries passed their entire lives in a predominantly agrarian village-oriented environment, and that only a small minority were acquainted with urban patterns of living, however loosely the term ‘urban’ is applied.

Earlier in the same book, it is noted that:

the great majority of the people mainly consumed what they themselves produced or secured from their neighbours on the basis of customary arrangements.

An exact figure is impossible to nail down, but multiple authors have estimated that 80% to 85% of the population were dependent on agriculture in Bengal (Roy, 2010).

The transition into less reliance on agriculture happened significantly earlier in north-west Europe. Already by the 15th century in Europe, a substantial minority did not do agricultural labor. By 1700 AD, less than half worked in agriculture in some European countries.

As shown in the chart below, only very recently has India caught up to figures that were achieved some 300 years earlier in north-west Europe. To this day, agricultural productivity in India lags far behind the West (Fuglie et al., 2024).

Income data

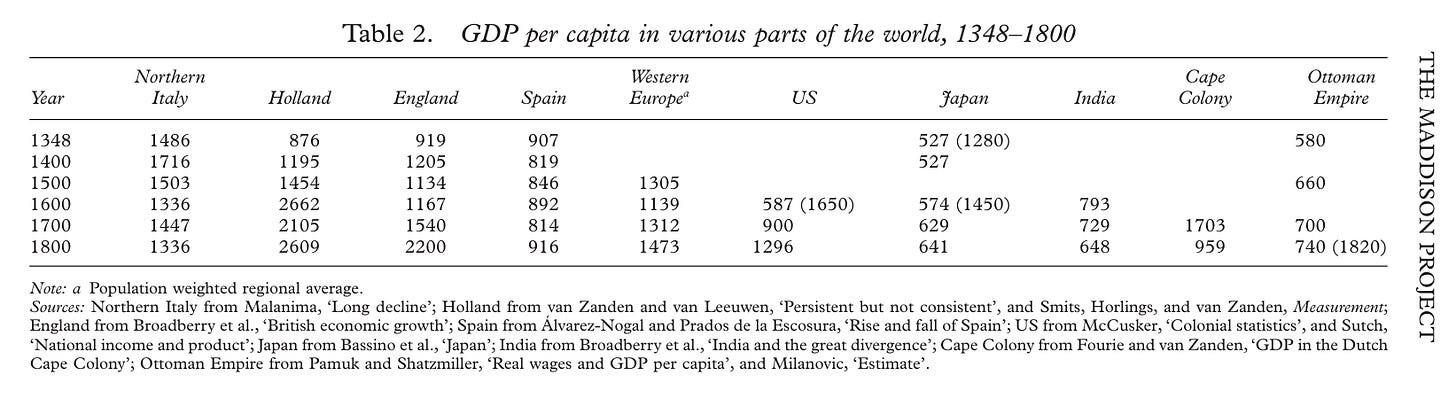

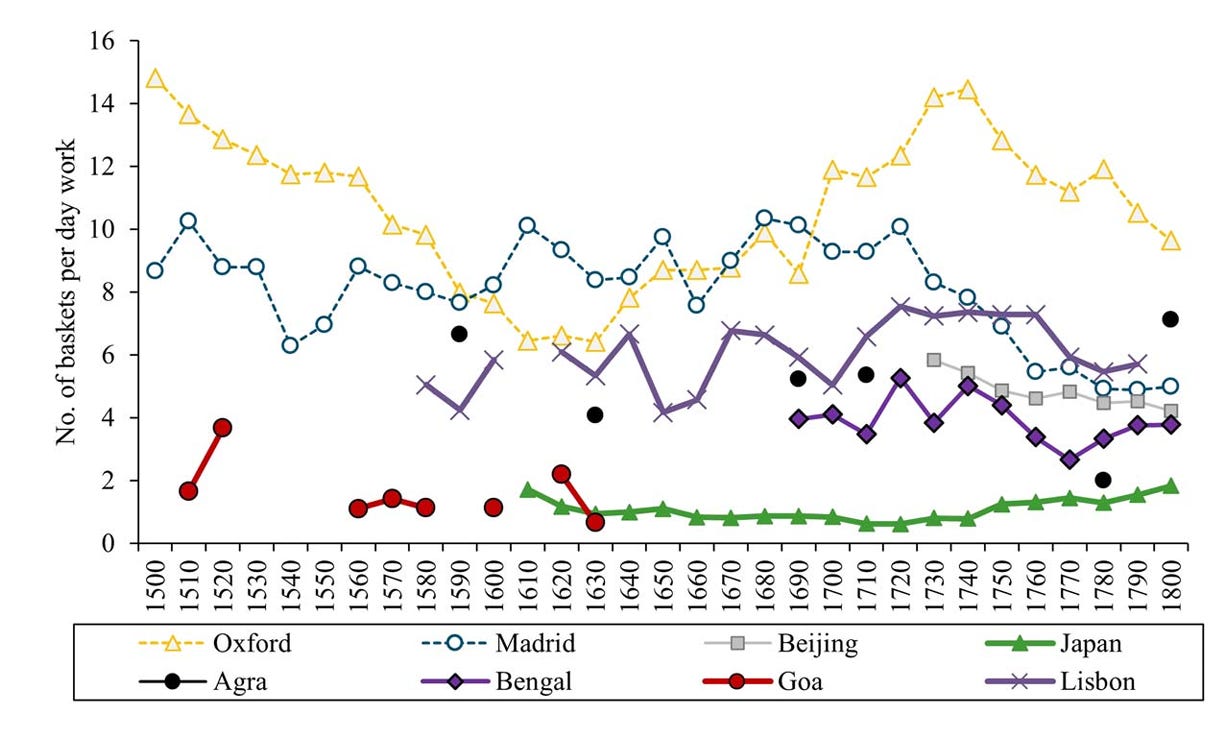

Maddison’s original GDP per capita estimates for precolonial India were largely “guesstimates.” However, recent work confirms the basic conclusion: living standards in India were substantially below that of England.

In a detailed case study of real incomes in Bengal in 1763, Tirthankar Roy demonstrates that these were much lower than those in England (Roy, 2010).

More recently, Broadberry et al. (2015) have provided new estimates. The table below shows that there was a significant difference between India and Britain by the year 1600, which grew over time.

Based on this work, Gupta (2019) analyzes the divergence in greater depth. Indian living standards modestly declined past 1600 AD, but relative to Britain the decline was great. The divergence was therefore more a product of British growth than Indian decline, though both contributed.

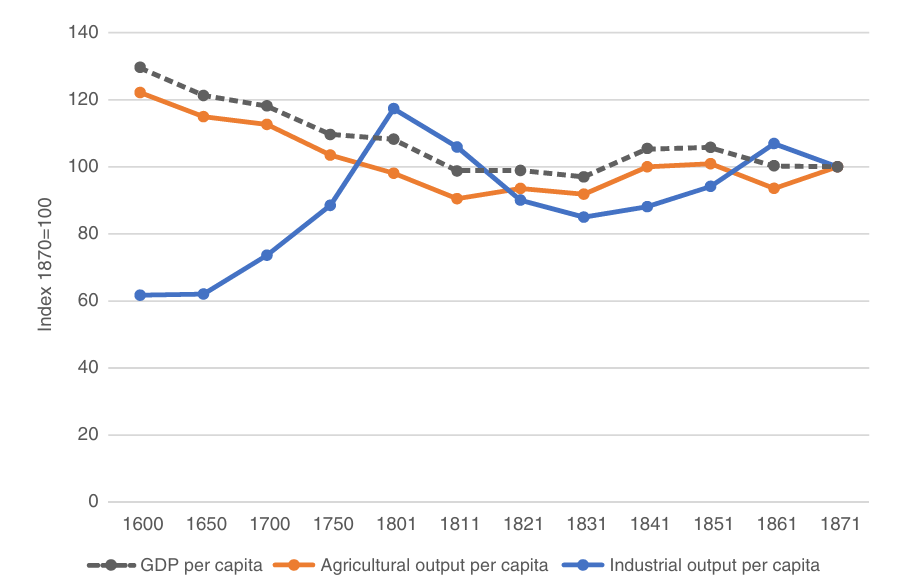

The author next decomposes the productivity into agricultural and industrial components. The following image conveys two important points: (a) trends in Indian GDP per capita and agricultural output per capita are nearly identical (indicative of India’s complete reliance on agriculture); and (b) Indian agricultural productivity (per-capita) decline preceded British colonization.

While colonialism happened after the productivity decline, the decline instead does coincide with a population growth starting from 1600 AD.

A straightforward Malthusian dynamic is a likely explanation (de Zwart, 2025). India was completely reliant on agriculture. Under Malthusian constraints, population growth outpaced agricultural output, thus the per-capita output declined as a result.

The conclusion of historically poor living standards in India has been greatly strengthened in recent years. This is due to work by De Zwart & Lucassen (2020), providing us with far more data—taking the number of wage observations from a few hundred to over 7500. The data primarily comes from Northern India, probably the wealthiest part of the subcontinent.

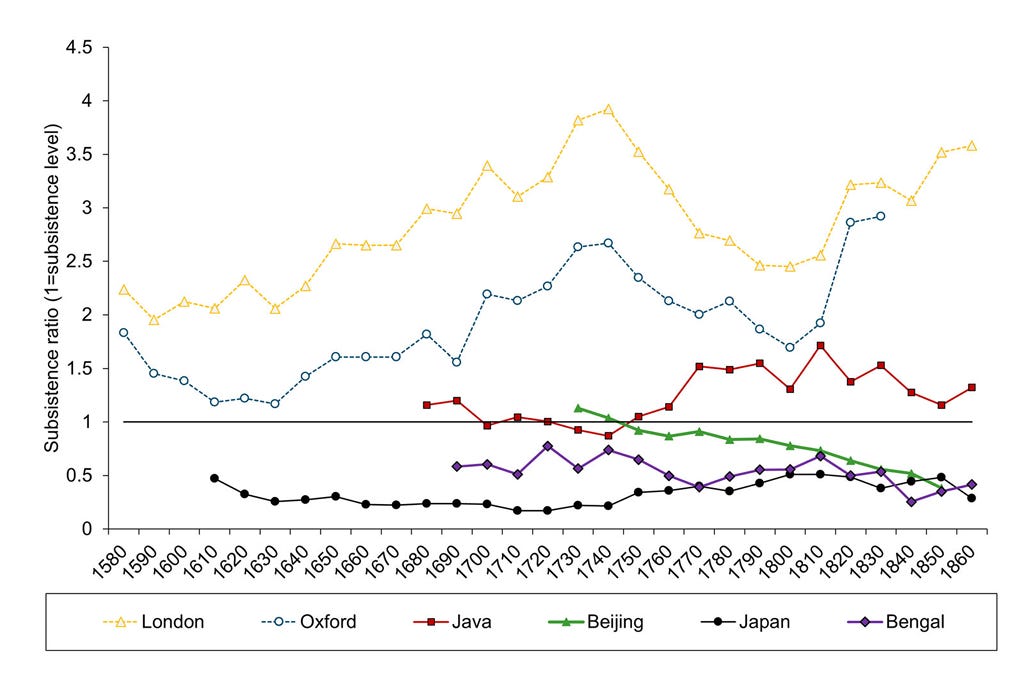

The wages of adult unskilled Indian men were very low. Since the 1600s, they have hovered around or even below subsistence level. This is shown for Bengal in the figure below.

In the words of the authors (de Zwart & Lucassen, 2020):

[I]t can be seen that the newly unearthed Indian wage data confirm the more pessimistic views of Indian early modern living standards (as put forth by Allen, and Broadberry and Gupta) rather than the more optimistic views (such as those of Parthasarathi and Sivramkrishna).

And in conclusion:

Our evidence does not support claims of comparatively high Indian real incomes in the eighteenth century nor views that suggest the decline was a post-1800 phenomenon, or even a purely colonial phenomenon

In agreement with Gupta (2019), they remark that “most of the decline in living standards preceded it,” i.e., preceded colonialism.

Finally, based on even earlier data from western India, recent work by Carvalhal et al. (2024) shows that the Great Divergence between England and India goes back even further.

Summary on economic divergence

Qualitative and quantitative evidence agree: commoners in precolonial India lived in poor conditions. Even in Northern India, wages were barely at subsistence level, if not below, and were declining in Malthusian fashion before colonization. The economic divergence between England and India was well under way in the 1600s.

In the upcoming part I will argue that the divergence, more broadly conceived, began much earlier still. There is more to societal development than income, and the foundations for the eventual economic divergence were being established centuries earlier. In particular, divergences in technology and human capital were underway significantly earlier.

Interrogating these foundations helps not only explain the economic divergence between the West and India. It also helps explain why there was more potential for an “East Asian growth miracle” than an equivalent “South Asian growth miracle.”

Understanding the divergence

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Patterns in Humanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.