No, India did not invent calculus

The true origin of calculus explained

Introduction

There is much to admire in the history of mathematics in India (see, e.g., Plofker, 2009). One can reasonably claim that, for most of the Middle Ages (after classical antiquity), the most proficient mathematicians were found in India.

Despite this perfectly admirable reality, many feel compelled to make exaggerated or downright false claims to embellish Indian mathematics. The most pervasive false claims are in the realm of calculus: that India invented calculus and/or that European calculus was derived from Indian methods.

In this piece I will first address what “calculus” is and why India didn’t invent it. Then I will refute the hypothesis that calculus was built upon a knowledge foundation transmitted from India to Europe, addressing some of the common arguments. The bulk of the article is spent on documenting the true story of how the development of calculus began in Europe.

These false claims are not only worth refuting because we should strive for accurate beliefs, but also because the story of how calculus emerged is fascinating in its own right.

India did not invent calculus

The misconception that India invented calculus is primarily promulgated by the popular media and in popular discussions. Few relevant experts of note will make such a claim. Addressing it nevertheless provides helpful context. The misconception rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of what “calculus” (and its invention) refers to in the history of mathematics.

Calculus is a systematic theory of integration and differentiation, and nowhere did such a theory exist before it was developed in Europe in the 17th century. The development of calculus at the very least entails three components:

Differential calculus. A systematic method for differentiating general curves. (I.e., for finding the instantaneous rate of change, or slope of the tangent, at any given point for general curves)

Integral calculus. A systematic method for integrating general curves. (I.e., for finding the area under general curves)

Fundamental theorem of calculus. To establish the connection between integral and differential calculus, unifying the two branches.

None of these three criteria had been previously satisfied anywhere—not in India, not in the Islamic world, nor by the ancient Greeks. Every assertion that calculus had been developed anywhere before the 17th century misses the crucial distinction between (a) applications of infinitesimal methods in specific contexts and (b) the systematic methods and theory that make up a true calculus.

It is true that methods for differentiating specific curves were known, and methods for integrating specific curves or objects were known, and the sums of specific infinite series were known. But nowhere had there been developed systematic methods for differentiating or integrating general classes of curves. Historically, infinitesimal methods had to be tailored to the specific problem at hand and didn’t generalize. Importantly, no one had connected the two branches of calculus into one (the fundamental theorem of calculus).

To appreciate what it means for calculus to be a systematic theory, consider Leibniz’s influential 1684 paper on differential calculus. In this paper, Leibniz presents a general algorithm for algebraically differentiating curves, general methods for finding minima and maxima, as well as general rules of differentiation (e.g., rules regarding constants, as well as the product and quotient rules). In the following years, he would publish similar papers on integral calculus (1686), and the fundamental theorem of calculus (1693).

Leibniz was far from the first to publish on infinitesimal analysis—he was building upon developments of the preceding century—but these papers were the first to publicly communicate a truly systematic theory of differentiation and integration. They gave the world calculus (the name is also derived from the title of Leibniz’s 1684 paper).

Beyond the development of the theory of calculus, of equal if not greater importance are its applications. After all, the reason calculus is held in so high regard is its potential to describe the world and solve problems. The Brachistochrone problem is a famous early problem in mechanics addressed by calculus in the late 17th century (including a solution by Newton). But in the 18th century, Euler would be the person to truly show the power of applied calculus.

Regarding the notion of “calculus” outside Europe, the historian of mathematics Victor Katz (1995) summarizes it well:

[S]ome of the basic ideas of calculus were known in Egypt and India many centuries before Newton. It does not appear, however, that either Islamic or Indian mathematicians saw the necessity of connecting some of the disparate ideas that we include under the name calculus. There were apparently only specific cases in which these ideas were needed.

There is no danger, therefore, that we will have to rewrite the history texts to remove the statement that Newton and Leibniz invented the calculus. They were certainly the ones who were able to combine many differing ideas under the two unifying themes of the derivative and the integral, show the connection between them, and turn the calculus into the great problem-solving tool we have today.

There was no transmission from India to Europe

While calculus was clearly not invented in India, more often the weaker claim is made that European mathematicians learned certain basic ideas of calculus from India, from which Europe built calculus upon.

The hypothesis suggests that Jesuit missionaries in India in the late 16th century (1578 at the earliest) discovered Indian mathematics of the Kerala school—including trigonometric methods and basic ideas of calculus—and that this knowledge was transmitted to correspondents in Europe from which it eventually disseminated via scholarly networks (Plofker, 2009).

Of course, even if this was true, calculus would still be a European invention, as that’s where the systematic theory of integration and differentiation was developed. But this is a moot point—there is no good reason to believe that such a transmission occurred at all.

The basic problem with the transmission hypothesis is that it lacks any historical evidence. As expert on the history of Indian mathematics Kim Plofker (2009, p. 252) writes:

There are no known records of sixteenth- or seventeenth-century Latin translations or summaries of these mathematical texts from Kerala. Nor do the innovators of infinitesimal concepts in European mathematics mention deriving any of them from Indian sources.

Moreover, as Plofker also notes, the European infinitesimal techniques used in the early developments of calculus do not resemble the Indian methods, but instead resemble those of their Hellenistic forerunners. This important point will be elaborated upon in the section on how the development of calculus truly began.

Similarly, David Bressoud (2002) writes:

There is no evidence that the Indian work on series was known beyond India, or even outside Kerala, until the nineteenth century.

The historian of mathematics Victor Katz (1992) has also stated that he remains unconvinced (not just specifically regarding an Indian transmission of calculus, but also regarding certain other claims of an Eastern impact on Western mathematics):

Although there were clearly wide-ranging mathematical developments in China, India, and the Islamic world, Joseph [in The Crest of the Peacock] was not able to convince me that the mathematics of these non-Western cultures had a significant effect on the development of European mathematics. In fact, if Europeans had been aware of this work, it would have saved them many centuries of struggle with the same ideas.

Ugo Baldini (2009) has raised many strong points against the Indian transmission hypothesis. Among the mathematicians in the Jesuit Society, practically all of them were destined to China, not India. Regardless if their perception was justified or not, the Jesuits perceived the scientific traditions of China to be more worthy of attention.

He also summarizes the implausible circumstances that are implied by the transmission hypothesis:

As evident, the ideal situation implies a number of circumstances which could hardly occur together: A Hindu – presumably a Brahmin – should have allowed a foreign person, who was also his rival in religion, to get in touch with precious and reserved texts; the other person should have been highly proficient in both Sanskrit and mathematics; he should also have been so patient and curious about those texts’ content to overcome the barrier produced by unusual expressions and demonstration procedures. In front of this, it must also be recalled that, as a matter of fact, no hint about Indian mathematical texts – perhaps some elementary ones excepted – is found in Jesuit sources before 1650 at least, and no such qualified person seems to have existed among Indian missionaries in those years.

After carefully considering the plausible candidates, noting that none of them seem to have gathered any notable mathematical information from Kerala, Baldini concludes:

Unless new evidence is found and some basically new circumstance is established, the only possible deduction seems to be that not only no information exists on a Jesuit mathematician having managed to study some advanced Indian text (not to say to transmit it, or its content, to Europe), but no serious clue appears of a scientific interchange not purely superficial and more than occasional.

Even proponents of the transmission hypothesis have been forced to admit that, despite a great deal of effort, the search for transmission evidence has left us empty-handed. As Almedia & Joseph (2009, p. 267) write:

The painstaking trawl of the mass of manuscript and other materials mentioned earlier in this Report has yielded no direct evidence of the conjectured transmission. We therefore have to report that on the basis of the evidence of the documents studied so far that the evidence supports the null hypothesis [of no transmission] formulated earlier. Thus the European Renaissance developments of the prototypical calculus may well have been independent of the developments in this subject in Kerala some centuries earlier.

In short, there is a total absence of historical evidence for an Indian transmission. And contrary to common belief, absence of evidence is evidence of absence. In a mathematical culture as heavily documented as 16th and 17th century Europe, you would expect to find plenty of evidence of such a transmission if it were true. After all, this was after the printing press and the establishment of postal services. There is an abundance of textual records from this era, and they have seemingly left us with no detectable trace of a transmission.

On “Circumstantial evidence” for transmission

Despite the lack of direct evidence, a select few still maintain that a transmission did occur. For example, in The Imperishable Seed: How Hindu Mathematics Changed the World and Why this History was Erased, Kamble (2023) admits that “no record of the Kerala mathematics having been transmitted to Europe has been found”, yet he still argues in favor of the transmission on the basis of “circumstantial evidence.” A similar case is forwarded by George Gheverghese Joseph in the The Crest of the Peacock (3rd ed), though Joseph is more tentative in his conclusions.

The premise of Kamble’s argument is that a “sudden and unexplained flourishing of mathematics and science in Europe” occurred after Jesuits arrived in India in 1578, and that a number of suspicious ‘coincidences’ suggest a transmission occurred.

This premise is false. Many of the most important advances in mathematics, technology, and science in Europe occurred in the centuries leading up to 1578 (e.g., solutions to the cubic and quartic equations, advances in symbolic algebra, and trigonometric advances; the mechanical clock and printing press; the observation of a supernova, and advances in anatomy, and Copernicus’s heliocentric model).

When the development of infinitesimal analysis began (which largely did fall in the latter part of the 16th century), Europe was already fully accustomed to mathematical and scientific advances. The transformative advances of the 17th century were a continuation of processes already ongoing before 1578. Moreover, many of the innovations of the ‘Scientific Revolution’ had no equivalent outside Europe, and thus clearly cannot be explained by imitation of outsiders. The incredulity aimed at the invention of calculus is unwarranted.

Nevertheless, Kamble is determined to frame history through the lens of a “sudden” change caused by a transmission, resulting in a distorted history with relevant details and context omitted. He forwards three ‘coincidences’ which together supposedly show that a transmission must have occurred. Let’s see how compelling they are.

Purported “coincidences”

Trigonometric tables

The first purported major “coincidence” is that Christoph Clavius in 1608 published a table of sines accurate up to 7 decimal places, “without either explaining the method he used in obtaining the values or mentioning the source.” Indian mathematicians already had sine tables accurate to 7 decimal places, so this is suspect according to Kamble.

This argument can be dismissed because we know that Clavius’s sine tables were taken from Reinhold’s 1554 table (Roegel, 2021). That is, it was based on work prior to Jesuit contact in India. The trigonometric methods were also explained in Clavius’s previous publication Astrolabium (1593).

The author also neglects to mention that the German Johannes ‘Regiomontanus’ Müller had already calculated a sine table to 7 decimal places more than a century prior to Jesuit contact. Regiomontanus’s sine table was completed in 1468 (Roegel, 2021), and was well known to Clavius. There is no strange ‘coincidence’ in need of explanation.

To make matters worse, starting around 1540, Georg Joachim Rheticus was already working on trigonometric tables with accuracy that far exceeded tables in India, or anywhere else for that matter. These tables were calculated to an accuracy of 15 to 20 decimal places (depending on the angle). They took decades to complete, but he had begun long before the Jesuit contact.

The Tychonic astronomical model

The second purported “coincidence” is the Tychonic astronomical system proposed in 1588 by Tycho Brahe. The author claims that it’s “exactly the same” model as one proposed by the Indian astronomer Nilakantha in 1501.

One gets the impression that the two models share remarkably intricate details that couldn’t plausibly occur by coincidence. In reality, they are simply both geoheliocentric models—that is, they both propose that all the planets except the Earth revolve around the Sun. This is relatively unremarkable.

Once you go beyond these gross similarities and look for more subtle astronomical ideas that could indicate a transmission, you find nothing. For example, in the same 1501 treatise in which his planetary model is presented, Nilakantha offers computational schemes for longitudes and latitudes of the Sun. Despite these being supposedly more accurate than contemporary European methods (Ramasubramanian et al., 1994), they were never adopted in Europe. These schemes were the primary focus of the treatise, not the implied astronomical model. If they were aware of Nilakantha’s work, why would they not adopt his superior computational methods?

The geoheliocentric (Tychonic) system (while ultimately incorrect) was the natural alternative to the geocentric (Ptolemaic) and heliocentric (Copernican) systems. A compromise between the two competing models, it attempted to address the problems of both (i.e., the overly complicated epicycles of the Ptolemaic system and the apparent lack of evidence for the moving Earth integral to the Copernican system). Proposing the geoheliocentric model is therefore completely understandable in context and requires no special explanation.

The Gregorian calendar reform

The third and final “coincidence” is that the Gregorian calendar reform was proposed in 1582, just four years after the Jesuit contact in 1578.

The calendar reform was motivated by the observation that the date of Easter was inaccurate. That is, there was an increasing divergence between the canonical date of the equinox and observed reality.

The author yet again neglects to mention that this issue had been known since the Middle Ages, and that there had been multiple earlier calls for reform prior to 1578 (including in 1515).

The issue became more pressing as the accuracy of astronomical observations increased—the divergence between the two became increasingly impossible to ignore. Much of this is due to the previously mentioned Regiomontanus, who in 1475 was invited to the Vatican in an attempt to undertake such a reform. Tycho Brahe, who had the most accurate pre-telescope observations, also remarked on the large discrepancies in his 1573 De nova stella (Dreyer, 1890, p. 52). Yet again, there is no ‘coincidence’ to explain.

Summary

The Indian transmission hypothesis is based on no historical evidence and the arguments proposed in its favor are flawed. The hypothesis rests on vague suggestions of ‘coincidences’ which, upon closer inspection, are not coincidences at all and amount to little of substance. If any uncertainty still persists, that should be eliminated in the following section in which I provide the actual account of how calculus emerged, grounded in incontrovertible historical evidence.

It is important to note that a central theme in the arguments forwarded by Kamble and Joseph is the charge of widespread Eurocentrism, which both of them believe underlies the unwillingness to accept an Indian transmission.

But is this a case of people in glass houses throwing stones? Perhaps the eagerness to adopt such a hypothesis on the basis of so flimsy evidence (at least in the case of Kamble), as well as their own refusal to accept the mainstream explanation (which boasts far more evidentiary support), is itself an indication of a bias in the opposing direction?

Contrary to Kamble or Joseph’s suggestions, the reason that the Indian transmission hypothesis is widely rejected by experts is not Eurocentrism. Rather, the hypothesis is based on no solid evidence and, just as importantly, the true origins of European calculus are already well understood and documented. The transmission hypothesis not only lacks evidentiary support, it is also unnecessary. It is being presented as an explanation to an unexplained mystery. But there is no real mystery.

How calculus truly came to be

Calculus was not invented over night. The advances of Newton and Leibniz were not just the product of their own ingenuity, but also the culmination of countless contributions of earlier mathematicians.

Prerequisite mathematical steps first had to be taken. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Europe saw rapid advances in algebra (e.g., solutions to the cubic and quartic equations) and in trigonometry. Starting in the mid-16th century, European algebra morphed from fully verbal form to an increasingly symbolic form. In the early 17th century, geometry also became conceptualized algebraically, with curves being described with equations and visualized in a coordinate system. The symbolic and algebraic advances provided a universal language from which general methods of calculus could be developed.

There were structural factors aiding mathematical and scientific development too. Most notably, the invention of the printing press (c. 1440) and the establishment of the international postal service (1490) led to a revolution in communication and sped up the rate of innovation in all of science and mathematics.

The era’s scientific “fashion” even played a role. In the 16th and 17th centuries it was motion that became the subject of fascination and investigation, regardless if it was motion of planets or of falling bodies on earth. Necessity is the mother of invention and calculus was the tool necessary for describing motion.

However, the proximate cause of the rise of infinitesimal analysis in Europe was the reintroduction of high-quality translations of ancient Greek works. These ancient works contained the precursors of calculus which Renaissance mathematicians built upon. In contrast with the Indian transmission hypothesis, the direct evidence in favor of this assertion is overwhelming.

The influence of ancient Greek works

Though the ancients never came close to developing a systematic theory of integration and differentiation (i.e., calculus per se), they had nevertheless studied basic aspects of calculus. Among all the mathematicians from classical antiquity, Archimedes was the one who took ‘proto-calculus’ the furthest.

In his treatise On Spirals, Archimedes was able to find the tangent of a specific spiral. In Quadrature of the Parabola, he masterfully calculated the area enclosed by a parabola and a line segment, using what has come to be known as the “method of exhaustion.” These two works illustrate ancient proto-calculus at its best, being early precursors of differential and integral calculus, respectively.

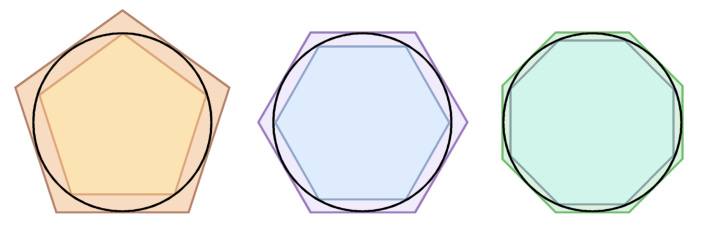

More well known, Archimedes also used the ‘exhaustion’ procedure to approximate π. He inscribed and circumscribed a circle with regular polygons. The perimeters of the polygons provided lower and upper bounds of the circumference of the circle. The greater the number of sides used for the polygons, the better the approximation.

As part of the Renaissance revival, several ancient mathematical works had already been translated. The quality of many early translations was poor, however, because those responsible were often not mathematicians themselves and they were not based on the original Greek manuscripts.

In the 16th century, a concerted effort was made to translate ancient mathematical works from original Greek, and for them to be prepared by mathematicians (Katz, 2009, 3rd ed., p. 407). This led to a new wave of high-quality translations, and their dissemination aided by the printing press. The transmission of ancient Greek knowledge, not a transmission of Indian knowledge, explains the ‘sudden’ rise of infinitesimal analysis in Europe. The earliest developers of calculus in Europe were all directly inspired by ancient works, especially those of Archimedes.

As historian of mathematics Jens Høyrup (2022) writes:

The decisively productive problems taken up by the 17th-century mathematicians came . . . from Archimedes, Apollonios, and Pappos; they were wholly different from anything circulating in or in the vicinity of the abbacus environment.

The Northern Renaissance only discovered Archimedes in the 1530s. Initially, Archimedes was mainly revered as an inventor. Gradually the appreciation for Archimedes the mathematician grew, but it took a few decades before this appreciation was converted into substantive engagement with his mathematics (Høyrup, 2017).

In De subtilitate (1550), Gerolamo Cardano placed Archimedes first in a list of great minds, and Federico Commandino (1509–1575) held the opinion that “that one can hardly call himself a mathematician who has not studied the works of Archimedes” (Høyrup, 2017).

Commandino was one of the most important translators of the Renaissance. In 1558, he published Greek-to-Latin translations of many of Archimedes’s works. Being a competent mathematician himself, Commandino’s translations and corresponding commentaries were of the highest quality and they were exceptionally influential.

In a 1586 book on statics, Simon Stevin applied an Archimedean principle to demonstrate that the center of gravity of a triangle lies on its median. He directly references the work of Archimedes and Commandino. Stevin also argued that one could fill the triangle with an infinite number of inscribed parallelograms, an early move towards a limit concept (Boyer, 1959).

But François Viète would be the first mathematician to make creative use of Archimedean mathematics (Høyrup, 2017). In his Variorum (1593), Viète became the first to discover an infinite product, drawing direct inspiration from Archimedes. Viète’s method was a variation of Archimedes’s approximation of π, using an exhaustion-like procedure of inscribing a circle with a sequence of polygons. The Variorum contains an abundance of references to the Greeks (Høyrup, 2022). Already on the first page does Viète mention Archimedes.

Countless other mathematicians would soon follow suit in building upon ancient Greek works. Fascinated with Archimedes’s approximation of π, Ludolph van Ceulen (1540–1610) emulated his method and calculated the first 35 digits of π by doubling the sides of an inscribed square an incredible 60 times (Cipra, 2009). In 1606, Luca Valerio (1553–1618) used the methods of Archimedes to find volumes and centres of gravity of solid bodies.

The next important step towards calculus was taken by Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), the greatest mathematical astronomer of his time. In Astronomia nova (1609), he computed the time elapsed between any two points in a planet’s orbit. He was also directly inspired by the exhaustion procedure Archimedes had used to approximate π. Kepler had become acquainted with Archimedes’ work through Commandino’s 1558 translation and it made a great impression on him (Aiton, 1976).

As Kepler himself tells us (Astronomia Nova, chapter 40, translation by Donahue):

For I had remembered that Archimedes, in seeking the ratio of the circumference to the diameter, once thus divided a circle into an infinity of triangles – this being the hidden force of his reductio ad absurdum [proof by contradiction]. Accordingly, instead of dividing the circumference, as before, I now cut the plane of the eccentric into 360 parts by lines drawn from the point whence the eccentricity is reckoned.

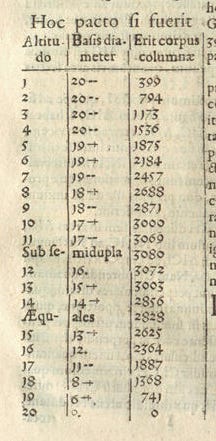

Kepler took to heart the idea that one can approximate complicated geometrical shapes by using sufficiently many simpler shapes, and developed further upon it in his book Nova stereometria doliorum vinariorum (1615). Here he calculated the volumes of solid objects not considered by the ancients: wine barrels.

A barrel’s exterior could be approximated by infinite number of cylinder strips of varying width, he reasoned, and he used this to integrate the volume of the whole barrel. The book also contains an early step in differential calculus in the form of analyses of maxima and minima. Kepler analyzed how a barrel should be proportioned if one wants to maximize its volume, and then went on to consider similar questions for other shapes. He made the important observation that the rate of change is small where maximal value is attained (dy/dx = 0, as we would say). In the preamble of this book, Archimedes is once again explicitly referenced.

Kepler’s idea of splitting an object into infinite strips, which was inspired by the ancient method of exhaustion, was systematically expanded upon in Bonaventura Cavalieri’s Geometria indivisibilibus (written 1627, published 1635). This work introduced the “method of indivisibles”—the first major step towards integral calculus.

As is noted by Kim Plofker, an expert in Indian history of mathematics, these early European advances towards calculus bear no resemblance to Indian infinitesimal works. Indian infinitesimal techniques were applied in a trigonometric context (Plofker, 2001). Instead, the methods used by the Europeans during the early development of calculus, as well as the kinds of problems they tackle, resemble those found ancient Greek works (Plofker, 2009, p. 252):

[H]ow would Sanskrit texts on infinitesimal methods for trigonometry and the circle, transmitted no earlier than the late sixteenth century, have inspired the quite different European infinitesimal techniques used at the start of the seventeenth century? Mathematicians like Kepler and Cavalieri focused instead on mechanical questions such as centers of gravity and areas and volumes of revolution, as well as general problems of quadrature explicitly associated with the work of Hellenistic forerunners and of Renaissance geometers such as Nicholas of Cusa.

The problem with the Indian transmission hypothesis is not just that it lacks historical evidence. To maintain belief in it, you must also ignore the historical evidence altogether. Because once you look inside the early European infinitesimal works, it becomes abundantly clear who they were learning from—they explicitly tell us.

The increasing societal reverence and influence of Archimedes is also seen in Galileo’s works. In Two New Sciences (1638), Galileo praised Luca Valerio, referring to him to as the new Archimedes of his age. He also gave an Archimedean demonstration of the quadrature (integration) of the parabola and included in an appendix some work on centers of gravity (Boyer, 1959).

One could list countless other examples of ancient Greek inspiration, but just one more will do. In De dimensione parabolae (1644), Evangelista Torricelli (1608–1647) gave 21 different proofs of the quadrature (integration) of the parabola. About half of these used the ancient method of exhaustion, and the other half used the new method of indivisibles. One of the proofs was essentially the one Archimedes himself gave in his treatise On the quadrature of the parabola, extant and well-known amongst European scholars at the time (Boyer, 1968, p. 391). In 1645, Torricelli also calculated the length of a logarithmic spiral based on infinitesimal methods he had learned from Archimedes, Galileo and Cavalieri (Boyer, 1968, p. 376).

It would take a couple more decades before a fully systematic theory of calculus would emerge (Leibniz’s trio of influential papers were published in 1684, 1686, and 1693, and Newton’s unpublished calculus was completed in 1671). But from the 1620s onward, its development was proceeding at rapid pace. While the early stage built upon an ancient Greek foundation, through the cumulative efforts of European mathematicians of the 17th century, infinitesimal analysis was developing far beyond what the ancients had achieved.

In the following sections, I will describe the steps that were taken towards developing systematic infinitesimal methods and theory, and how this ultimately culminated in calculus proper as achieved by Newton and Leibniz. I will also describe how the theory of calculus became a powerful scientific tool for describing natural phenomena. Lastly, I will discuss the plausibility of an alternative reality in which India or even ancient Greece invented calculus.

For those interested, I have also included an appendix of advances in European mathematics in the 15th and 16th centuries that preceded European investigations into infinitesimal analysis.

Towards a general theory of calculus

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Patterns in Humanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.