Mental Health and Social Stratification

In this post I summarize some research on the importance of mental health for social outcomes and discuss some of the implications for social stratification.

Mental Disorders in the Labor Market

Mental disorder is a great burden for the people who suffer from them and for society. People with mental disorders often struggle in the labor market. The burden differs between kinds of mental disorders and with the severity of the symptoms experienced, but few are as illustrative as schizophrenia. A Danish nationwide cohort study looked at the association between early-onset schizophrenia and various life outcomes. They found that an astonishing 85-90% were not employed between the ages 25-61, an odds ratio of unemployment reaching a value of 50 at the general population’s prime working age. Simply put, effect sizes of this magnitude are practically never seen in the social sciences. The same study also found that, between the ages 25–61, their cumulative earnings were on average a mere 13.6% (less than one seventh) the amount of that of people who were not diagnosed with schizophrenia.

The extreme burden of schizophrenia means that nearly all affected individuals are downwardly mobile, resulting in an overrepresentation of people with schizophrenia in the lower socioeconomic classes. Unemployment and homelessness are common outcomes. Indeed, schizophrenia and intellectual disability are both highly overrepresented among the homeless population. A review found that an estimated 76% of homeless people in high-income countries suffered from a mental disorder, with substance use disorders and schizophrenia being the most common.

Schizophrenia, like many other mental disorders, is substantially heritable. Due to the downward social movement of affected individuals and of people with heightened risk (e.g., due to lower IQ), genetic variants influencing schizophrenia risk are more common in low socioeconomic environments. This was confirmed in a large study from Sweden that concluded the primary reason that schizophrenia is more common in more deprived neighborhoods is likely because the genetic risk variants have higher frequency.

While most mental illnesses are not as debilitating as schizophrenia, most of them do result in downward mobility on average. A recent Danish population-based cohort study revealed that a person with a mental disorder on average lost 10.52 years of working life compared to the general Danish population. Of the 10.52 years, 7.54 years were due to disability pension, 2.24 years were longer periods of unemployment, and the remaining years (0.74) due to other causes (e.g., earlier death). Overall, 9.47% were diagnosed with a mental disorder, meaning a randomly chosen person from the general population loses on average 1 year (10.52 × 0.0947) of working life due to mental disorder.

Even when compared with their undiagnosed siblings from the same family, people with psychiatric diagnoses have more days of unemployment and lower educational attainment on average. This is particularly true for externalizing symptoms, such as conduct problems and substance abuse disorders. A large Swedish study found that an overall index of genetic risk for psychopathology was associated with lower income and lower educational attainment, among many other things.

Mental Disorders and Education

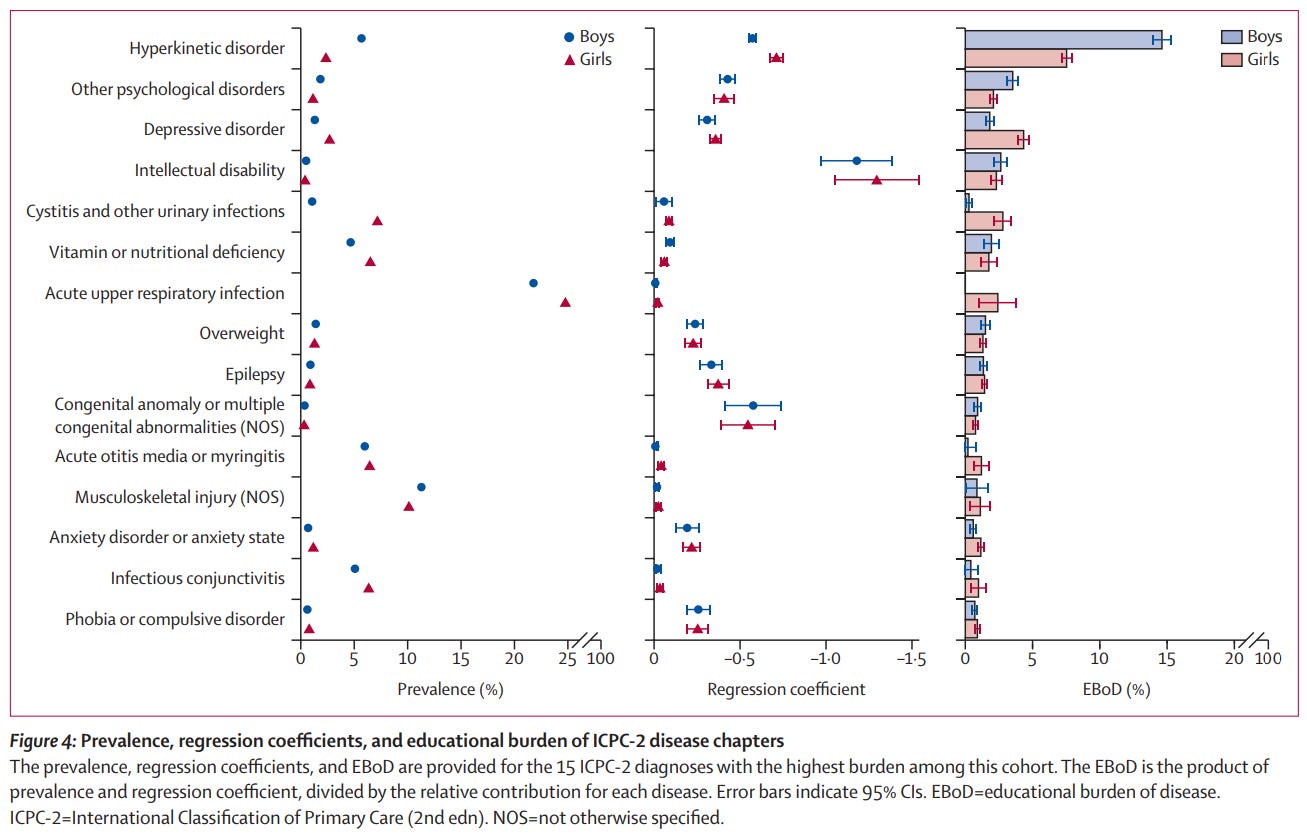

As noted in some of the studies above, the effects of mental disorders are also observed in educational performance. A large Norwegian cohort study estimated the educational burden of disease (EBoD) based on grade point average (GPA) at the end of the compulsory school aged circa 16. They compared siblings from the same family where one was affected by the illness and the other wasn’t to estimate the average absolute effect of the disease on GPA (see image below). Overall, mental health disorders accounted for nearly half of the overall disease burden. When affected, the largest effect by far was for intellectual disability, a testament to the importance of intelligence in education. However, due to their much greater prevalence than intellectual disability, hyperkinetic disorders (notably including ADHD) have the largest aggregate society-wide burden of all disease categories. Large Danish and Finnish studies have found similar results for the effect of mental illness on GPA, likelihood of reaching final grade examination, and on the risk of being long-term not in education, employment or training.

Mental Disorders and Crime

Most types of crime, violent crime included, tend to be more common in more impoverished neighborhoods. While often blamed on poverty itself, an important contributor is likely the selection of higher-risk individuals into these environments. We have just seen that people with mental health issues have lower educational attainment and perform worse in the labor market, and that this was particularly evident for conditions such as schizophrenia and for people with externalizing issues. But these conditions are not just associated with labor market or educational performance; they are also risk factors for violent crime.

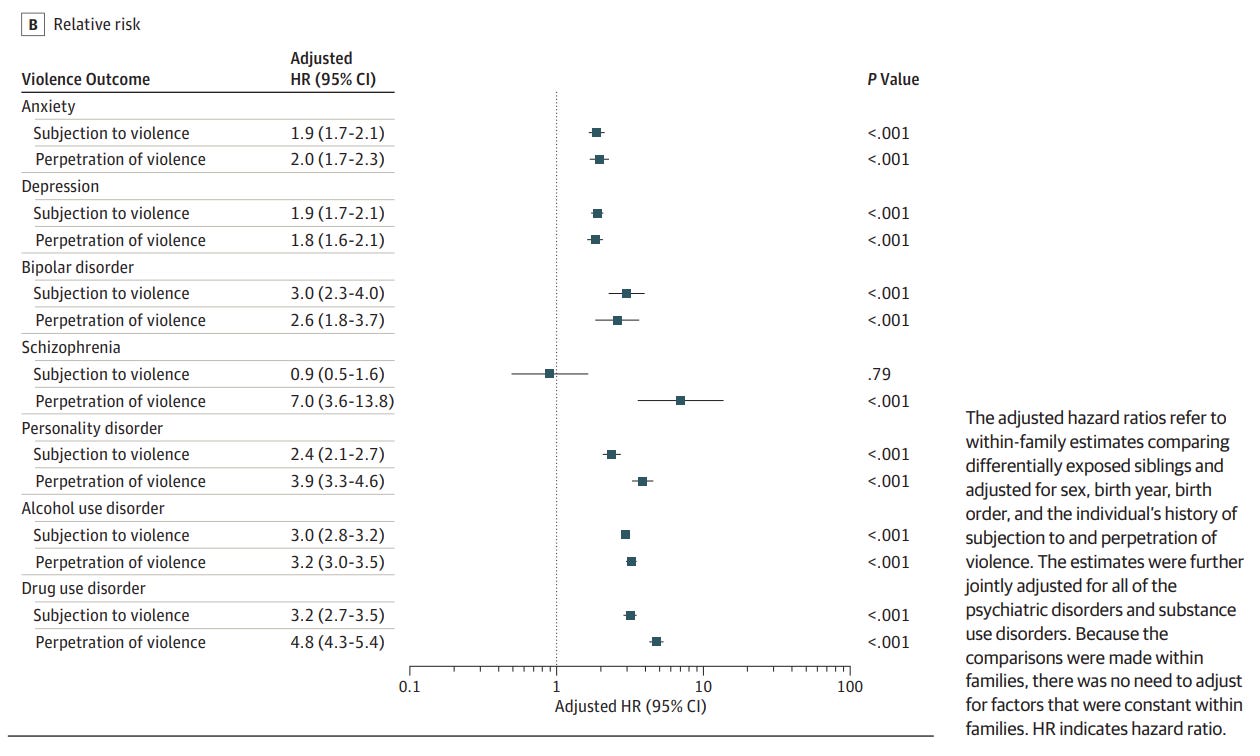

A Swedish nationwide cohort study finds that people with psychiatric disorders are approximately 4 times more likely to perpetrate violence than their siblings without psychiatric disorders. The hazard ratios for various psychiatric disorders can be seen below. For internalizing disorders (anxiety and depression disorders) it is around 2, for externalizing disorders (e.g., substance use disorders) it is closer to 4, and for schizophrenia even higher. Considering even more serious violence, a review analyzing evidence from multiple countries found that people with schizophrenia commit homicide at rates almost 20 times higher than those without.

The modestly higher rates of violence for internalizing symptoms can likely be mostly explained by substance abuse. A recent large study of individuals with community sentences found that those with psychiatric disorders were more likely to violently reoffend. However, for internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety, most of this disparity is gone in cases without substance abuse. The higher rates of violent reoffending among people with psychiatric disorders have been found in other earlier studies. They also find that the reoffending rate increases with the number of diagnoses (see below).

The sibling comparisons show that the greater rate of violence among people with psychiatric diagnoses is not due to confounding from socioeconomic factors. It also makes it less plausible that purely financial interventions can adequately address the gaps. But that does not mean nothing can be done. As we have seen, avoiding substance abuse can likely substantially reduce the problems. In some cases, the symptoms can, at least to some extent, be alleviated with proper medication. For example, rates of violence in some disorders can be substantially reduced with antipsychotic medication. This has been shown with large quasi-experimental designs where individuals’ risk is compared to themselves between periods where they do and do not use medication (see here, here and here). The efficacy of antipsychotic medication on lowering violence has also been shown in randomized controlled trials summarized in a Cochrane report.

In conclusion, mental health is important for social success. Mental disorders are risk factors for both downward social mobility and crime; relevant to the clustering of crime in more impoverished neighborhoods. Evidence shows that there are ways to reduce the problems associated with mental disorders to some extent.

1) I'm not surprised. I have interacted with a bunch of schizophrenic people. These people are so different from "normal" people.

2) Also I suspect that other mental illneses are somewhat over-diagnosed e.g. depression, adhd, autism. People who are on the left side of the bell curve for happiness, attention, social skill are probably often falsely diagnosed with the above mentioned disorders.

Not so with schizoprhenia probably. Hallucinations isn't a bell curve. Normal people don't have them at all. So people diagnosed with schizophrenia really have severe mental problems which won't simply go away after some time

3) I'm not sure that schizophrenia is more common among lower classes cause of schizophrenic people being downwardly mobile (which is true). IIRC I remember reading feritlity of schizophrenic people is pretty low. Low IQ people are just more prone to develop schizophrenia than high IQ people (iirc this is also Greg Cochran theory). So ofc it't occurs more often in the lower class